<< continued from page 3

Catherine Deneuve in Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg) [1964]

....

|

Francois Truffaut followed Jules et Jim with La Peau Douce (Soft Skin) (1964) another story about an ill-fated love triangle, but this time in a contemporary setting. Despite excellent perfomances and a compelling narrative the film was not a financial success, and, over the next few years, Truffaut’s career slowed as he worked on his book about Alfred Hitchcock, whilst struggling to get his film adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s Farenheit 451 off the ground. When he came to shoot it the larger scale production was difficult for Truffaut, used to working on low budgets and unable to communicate easily with the English speaking crew, and the resulting film failed to match its initial conception.

Jacques Demy had his greatest success with his third film Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg) (1964). The film, staring a 20-year-old Catherine Deneuve, tells a tragic story of everyday life but is transformed by Demy into a tender romance in which all the characters sing their lines and the town is painted in a range of beautiful colours. The film was a critical and commercial success, winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes. He followed this with the equally captivating Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (The Young Girls of Rochefort) (1967).

Le Feu Follet (The Fire Within) [1963] .

....

|

Louis Malle’s typically diverse range of 1960’s films included Vie Privee (A Very Private Affair) (1962) in which Brigitte Bardot played a virtual parody of her real life persona; Le Feu Follet (The Fire Within) (1963), the powerful study of a writer trying to find a reason not to kill himself; the internationally successful Viva Maria! (1965) which teamed Brigitte Bardot with Jeanne Moreau in a tale of revolution in South America; and Le Voleur (The Thief) (1967), a comedy drama about a thief staring Jean-Paul Belmondo. After the failure of the last of these, Malle admitted he was tired of the mainstream film industry, and, in 1969, he travelled to India, where he made two uncompromising documentaries about the poverty he found there.

In 1962 Eric Rohmer made La Boulangere de Monceau (The Bakery Girl of Monceau) (1962), the first in what would become a celebrated series of films released over the next ten years under the title Six Moral Tales. Each of the films, which included Ma Nuit Chez Maud (My Night with Maud) (1969) and Le Genou de Claire (Claire's Knee) (1970), explored the entanglements, temptations and disappointments facing contemporary relationships. In them Rohmer established a cinematic style all his own, notable for its economical camerawork, warmly ironic tone, and strict fidelity to the true representation of reality.

More conventional in his approach than the other New Wave directors, Claude Chabrol’s mid-1960’s output failed to draw the attention accorded to his contemporaries. Out of step with the mood of the times, for a while Chabrol appeared to lose direction. Then came the series of psychological thrillers starting with Les Biches (The Does) (1968), and including La Femme Infidele (The Unfaithful Wife) (1969), and Le Boucher (The Butcher) (1969), which established his world-wide reputation.

Jacques Rivette’s debut feature Paris Nous Appartient (Paris Belongs to Us) (1960) had been a monumental undertaking, taking two years to make and featuring a cast of thirty actors. However it’s labyrinthean plot and uneven pace found little favour with audiences. His next film, Le Religieuse (The Nuns) (1966) was considerably more commercial, becoming a success de scandal when the government blocked its release for a year. The relatively straightforward narrative of this film was, however, uncharacteristic of the director’s vision, and, it was with the highly experimental and original films that followed, including L’Amour Fou (Mad Love) (1968), Out 1 (1970), and Celine et Julie Vont en Bateau (Celine and Julie Go Boating) (1974), that Rivette made a more lasting impact.

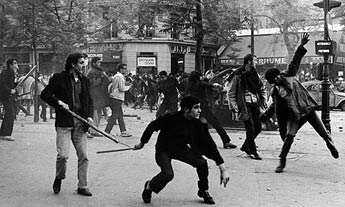

The Paris Riots, 1968

|

In the spring of 1968, a minor protest by students at Nanterre University quickly escalated, leading to major civil unrest all over France. On May 10th in Paris there was a violent confrontation between student demonstrators and the police. Over the following days discontent with the Gaullist government spread into the labour force and workers began joining in the protest with a series of strikes and factory occupations. Ultimately, the De Gaulle government held firm, and, partly because of divisions within the leftist opposition, the protests died away.

Earlier in 68, events in the world of cinema had helped to trigger the riots that followed. It began when Henri Langlois, who had set up and nurtured the Cinématheque Francaise, was fired as its head by the Minister of Culture Andre Malraux. Claiming administrative incompetence as his reason, Malreaux terminated the archive’s subsidy and moved to appoint a new head. The firing sparked protests among Parisian film students who continued to receive much of their education through screenings at the Cinematheque, as well as New Wave directors like Truffaut, Godard, Rivette and Resnais who proudly proclaimed themselves “children of the Cinématheque.”

Even the Cannes festival was drawn into the protest as Louis Malle and Roman Polanski resigned from the festival jury, and Truffaut and Godard burst into a screening and hung from the curtains to physically stop the festival from continuing. Support too came from abroad in the form of telegrams from world famous directors like Hitchcock, Kurosawa and Fellini. Eventually Malraux was forced to back down and Langlois was reinstated.

The Langlois affair showed that, despite their differences – both political and cinematic – the directors associated with the Nouvelle Vague could still come together as a group. Indeed, after their work came under attack from critics, and the film establishment began to reassert itself, they felt more willing to assert themselves as part of a movement than they had at the start.

As Truffaut wrote in a 1967 issue of Cahiers du Cinéma: “Before, when we were interviewed – Jean Luc, Resnais, Malle, myself and others – we said, ‘The New Wave doesn’t exist, it doesn’t mean anything.’ But later, we had to change, and ever since that moment I’ve affirmed my participation in the movement. Now, in 1967, we are proud to have been and to remain part of the New Wave, just as one is proud to have been a Jew during the Occupation.”

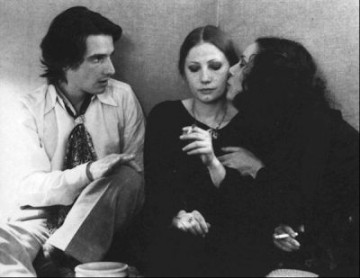

La Maman et la Putain

(The Mother and the Whore) [1973]

....

|

An enduring legacy of the French New Wave movement was the inspiration it provided for similar movements in other countries. In America, the “movie brat” generation of filmmakers that emerged in the late 1960’s and 70’s, was profoundly influenced by the storytelling techniques pioneered by the Novelle Vague directors. In Europe too, young directors in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Germany, and elsewhere, were motivated to break with the past and tell their own stories. Even further afield, in countries such as Japan, Brazil, and Canada, similar movements prospered for a while.

In France the success of the Nouvelle Vague continued to open doors for new directors. Barbet Schroeder (More (1969)) Jean Eustache (La Maman et La Putain (1973)), Andre Techine (Paulina s’en Va (1975)), and Philippe Garrel (L’Enfant Secret (1979), made up part of what could be considered a post New Wave second wave. They, and other directors like Jean-Claude Biette, Claude Guiguet, and Paul Vecchiali, began, like their predecessors, writing for Cahiers du Cinéma, before turning to filmmaking themselves.

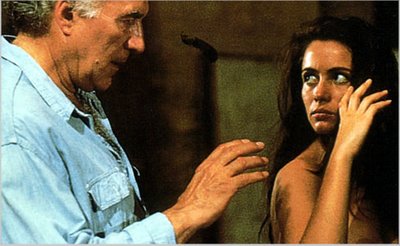

La Belle Noiseuse [1991] .

|

In the 1980’s a new generation of young directors emerged in France. Dubbed by the media the "New New Wave", the three main figures in the group, Jean-Jacques Beineix, Luc Besson and Leos Carax, were quick to distance themselves from the earlier movement, expressing anti-New Wave sentiments in interviews. Their films, which included the hits Diva (Beineix (1980), Subway (Besson (1985), Betty Blue (Beiniex (1986), The Big Blue (Besson (1988), and Les Amants du Pont-Neuf (Carax (1991), were criticized for favouring style over substance. Their style of filmmaking became known as the ‘cinema du look’, and, although popular, was felt by many to offer little more than slick visuals and alluring stars.

The tragic early death of Francois Truffaut in 1984 brought an end to the career of the best known and best loved of the French New Wave directors. His later work, although varied and not always successful, included such highlights as the Oscar winning Day for Night (1973), the poetic La Chambre Verte (The Green Room) (1978), and Le Dernier Metro (The Last Metro) (1980), a story of the Resistance which was a critical and box office triumph in France. Apart from his work, Truffaut himself has become an icon and inspiration for impassioned, idealistic young directors, determined to remake cinema on their own terms.

As for his Nouvelle Vague contemporaries, they continue making waves in the twenty-first century. Godard, Chabrol, Rohmer, Rivette, Varda, Resnais, Marker, and others associated with the movement, are all now auteurs in their own right with an international following. Their prolific output continues to challenge audiences and expand the boundaries of cinematic expression. Retrospectives of their work and new prints of New Wave classics continue to keep alive a cultural revolution that produced some of the greatest films ever made and changed the course of cinema history.

|