|

Director and Film Critic, Kent Jones |

Kent Jones is a film critic and documentary maker. He is the director of the New York Film Festival and the deputy editor of Film Comment magazine. His documentaries include Val Lewton: The Man in the Shadows (2007) and A Letter to Elia (2010). His new film Hitchcock/Truffaut tells the story of the famous interview with Alfred Hitchcock by Francois Truffaut that took place in 1962 and became a seminal moment in cinema history.

We spoke to Kent Jones about Hitchcock/Truffaut ahead of the film's cinema release in London.

The book Hitchcock/Truffaut was first published in 1966 and has since become a classic text of film studies. What happened to inspire you to want to make a film about it?

I was asked [laughing]… so that was the inspiration! Someone asked me, but I said yes immediately. It’s a film that I was very excited about making because it’s a book that has meant a great deal to me for – I mean I’m fifty-five – so for the last forty-three years of my life. Hitchcock’s work, and Truffaut’s work to a certain extent as well – but Hitchcock’s work has for me a deeper connection because I started looking at his films right around the same time as I read the book, and I’ve been re-watching them over and over since then. I’ve never even started to count how many times I’ve seen Vertigo or Rear Window or Psycho or Saboteur or I Confess – and so, in that sense as well, it was something that was exciting for me. Then there was the idea of making a movie that really looked at the question of filmmaking, at a moment when the idea of filmmaking is a little bit debased – sometimes a little, sometimes a lot – and looked at it in new and surprising ways. So those were all the things that were in my mind.

|

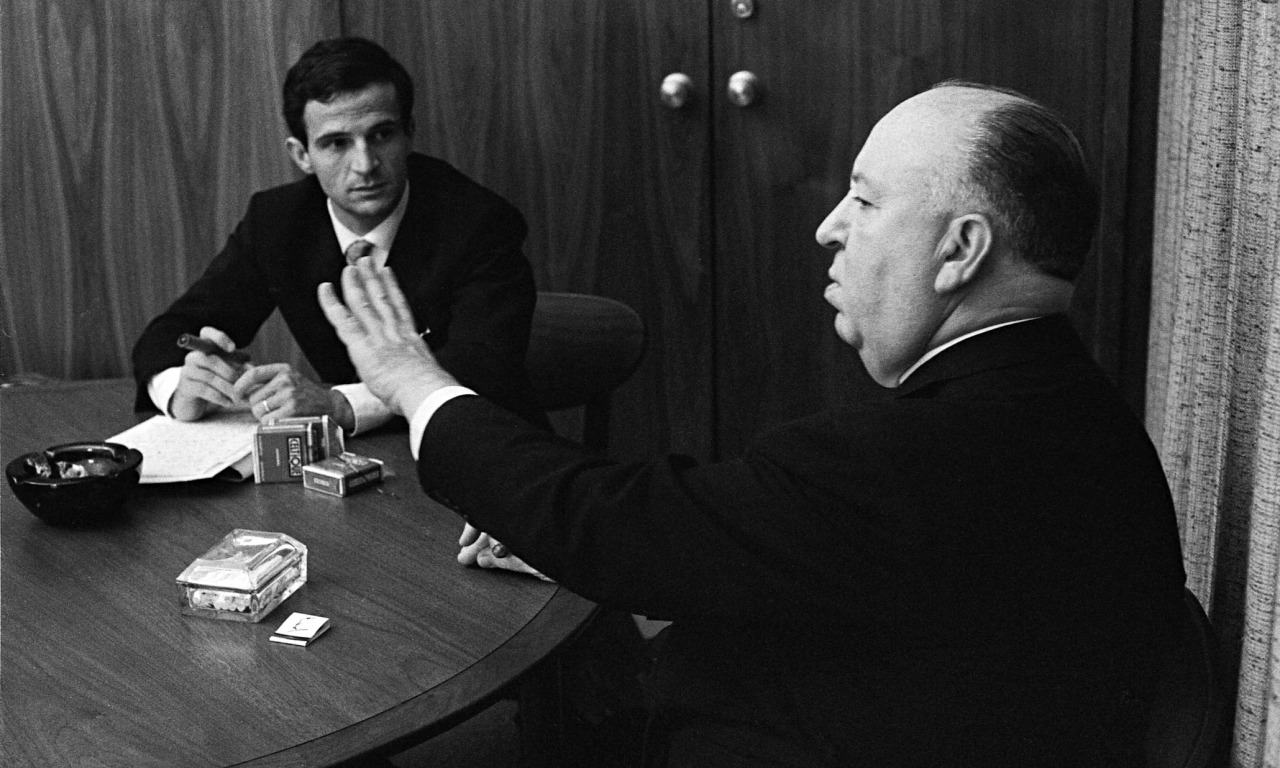

Truffaut and Hitchcock,photo by Philippe Halsman |

Others, including André Bazin, had interviewed Alfred Hitchcock over the years and tried to get him to talk seriously and in depth about his work, but it was Francois Truffaut who finally succeeded. What do you think it was about Truffaut that he was able to get Hitchcock to speak to him in such candour and detail about his work?

He was a filmmaker, that’s what makes the difference. It’s a very different thing when you have a critic talking to a filmmaker, it’s a very different dynamic. And of course Truffaut had spoken to Hitchcock as a critic previously – he and Chabrol interviewed him in the 50s. But that’s the difference. The other difference of course is the nature of the enterprise, which is Truffaut saying, “I want to do this book and look at all of your films, talk about your filmmaking themes and practices, and in so doing demonstrate why you are the most important filmmaker alive”. So obviously that meant a great deal to Hitchcock. Coupled with those things are the fact that the tapes were never meant to be heard; they were only meant to be transcribed and then turned into the book. So really you have Hitchcock in a very different situation from any other situation he was ever in – because usually it doesn’t matter who is interviewing him, his guard is up and he’s telling the same old stories embroidered from the set, “actors are cattle”, and so on. But with Truffaut it’s different and I think it begins with the fact that he’s a filmmaker.

For anybody who has read and come to know the book well over the years, hearing the audio-tapes of the interviews is something of a revelation. What dimension do these bring to the film and were there any moments from the tapes that stood out for you?

In general, I think if you know the book very well, as you say, it does come as a revelation. And it comes as a revelation because in the book Hitchcock appears to be very cold, precise, distanced and kind of lacking in humor, except for some not very good jokes that he tells. The tapes are another matter entirely – he’s very warm and very funny and very spontaneous. And Truffaut did not speak a word of English and so he was very dependent on Helen Scott who was translating every word. She got some right, some not so right. Then her translation was amended in France, then he worked on the book, then I believe it was re-translated back into English – that’s the way it reads to me. So it’s a kind of a remove from Hitchcock - so in general, that’s a revelation.

Also, the sense of him wondering if he should have spent more time on character is in the book, but you can hear him returning to it in the tapes. That’s fascinating and beautiful and very moving.

|

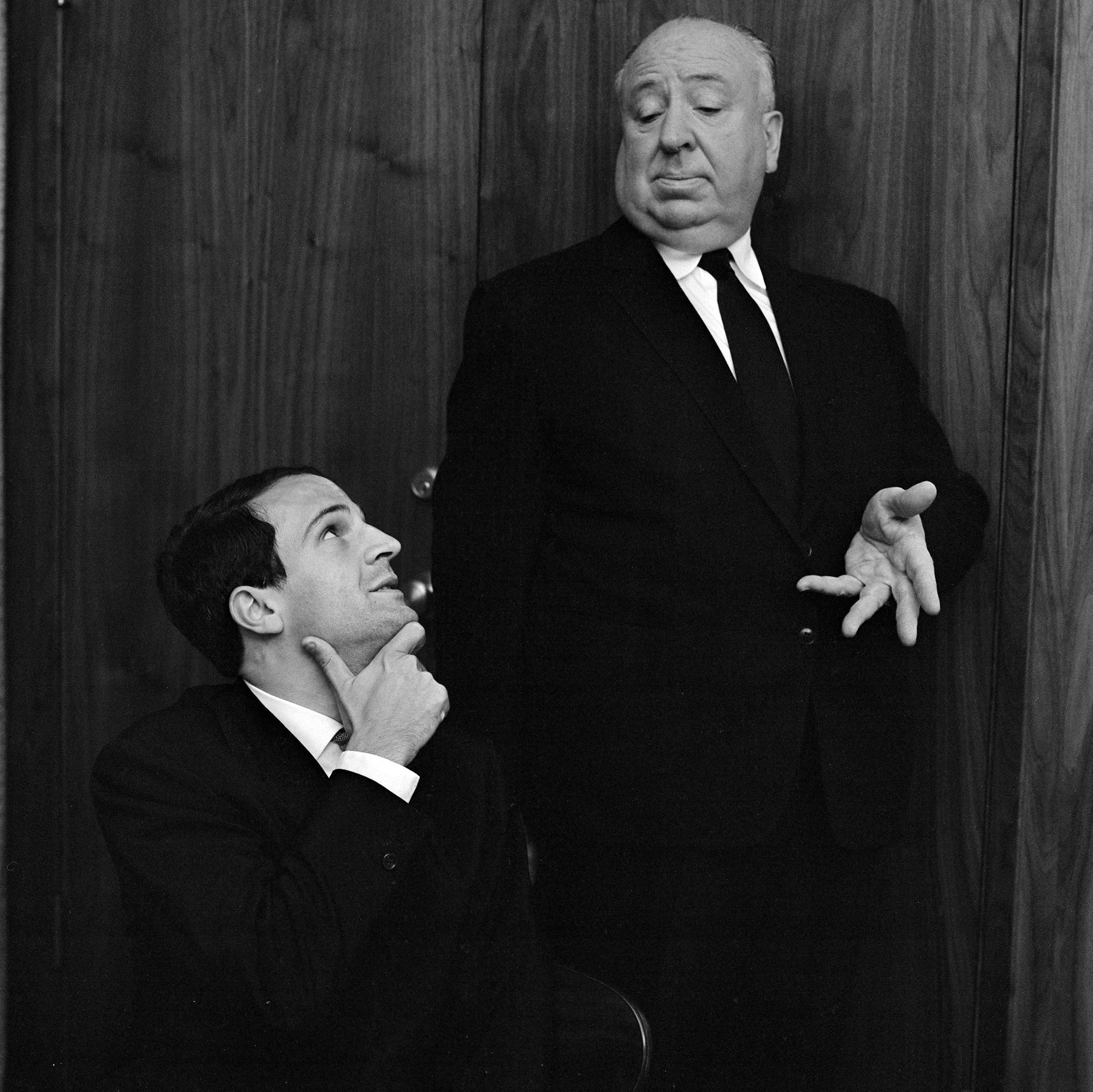

Director David Fincher discusses Hitchcock's work. |

Why did you decide to include interviews with a number of contemporary directors?

Because it’s a conversation between two directors about directing, so I wanted to keep it that way. I didn’t want to have experts or former collaborators or anything like that. I think generally that can lead to very predictable results, and I didn’t want to do a lot of commentary. What I wanted to do was have what is great about Hitchcock be born out in the images, then have the filmmakers talk about their relationship to the images and their relationship to the book. I decided that very early on, and I was really happy that I was able to stick to that and that the producers got it. And I was really happy that the people who were in the film said yes.

Much of the book and your film are concerned with Hitchcock’s use of cinematic language to convey meaning and emotion. What, in your view, do you think a filmmaker reading the book for the first time, or watching the film, could learn from Hitchcock about how to use cinematic language effectively?

|

Tippi Hedren in The Birds (1963) |

I think that a filmmaker could learn, for instance, from Hitchcock about the question of space and the economy of space. For example, when he describes how to use space and to use it dramatically, and to use the distance dramatically so that you don’t waste a shot. There’s a moment in the tapes that we didn’t use in the movie where he says, “never use an establishing shot to establish, always save it for when it’s going to have the most dramatic impact”. And he gives a very concrete example of this that we do use in the movie, which is the shot of Tippi Hedren recoiling on the couch from the sound of the birds outside the house in The Birds. They’re not in the house yet, but she’s hearing them and she’s recoiling, even though they’re not close to her. So he’s saying, “if I’d gone in closer then it wouldn’t have been as good, but by maintaining the distance that I did, you could see the nothingness from which she was shrinking”.

And this raises the larger point, that it’s not about how it feels when you’re on set; it’s about what it’s going to look like when it goes up on the screen. Now, one thing we do deal with in the movie, that I thought was really important, was the change in cinema. This was something that Marty Scorcese and David Fincher talk about a lot - how the centre of gravity shifted between actors and directors after the time of the Actors Studio. The group theatre in the 1930s paved the way for the Actors Studio, which was founded by Elia Kazan, Bobby Lewis and Cheryl Crawford, then turned over to Lee Strasberg. And from the Actors Studio you had Stella Adler, you had Sanford Meisner, you had Jeff Corey on the West Coast and Sandra Seacat and Herbert Berghof and Uta Hagen, and really you had a different approach to the question of acting. So that’s something that changes the dynamic in such a way that a lot of people now kind of forget about that part, or they lessen the part about how it’s going to look on the screen. There’s something that David Fincher said in the interview that we didn’t use in the film, but that’s quite pertinent here, in which he said that sometimes it’s like acting, but sometimes it becomes like an emotional playground. And David, by the way, is accused of the same kind of thing that Hitchcock is accused of, but he’s very attentive to actors. So the thing is that you have to strike a balance, and I think that’s something that is very important. On a broader level even than that though, for younger filmmakers, the idea that there is such a thing as a cinematic language is important because, I don’t know about you, but I see a lot of movies that are made by people that just don’t have any sense of that.

The documentary has a dramatic sense of style in its use of music and graphics in the titles, and in its structure and pace. Were you inspired by Hitchcock in your approach to these elements?

I kept the graphics to a minimum. There are a lot of films that have a lot of fancy graphics, and I really don’t like that. However I wanted the graphics we used to move dynamically, but with the music. And as far as the music goes, when I was first thinking about the music I thought, yes, let’s use some Bernard Herrmann music or something like that, then I thought no, that’s proper to Hitchcock. So we were using Johnny Greenwood’s film-scores as temp music, and then I went to a young composer named Jeremiah Bornfield and we played a temp score for him and he gave us something we really loved, that had that kind of dynamism to it and that had that kind of instrumentation. He didn’t duplicate it; he created something new. And I was really, really happy with it. As far as the tempo and pace of the film and how it works structurally, I mean, look, the film is a film about Alfred Hitchcock, but it’s also a film by me and I believe in concision already, so if I’m making a film about Alfred Hitchcock it’s going to be concise. I’ve had some nice comments from people saying it could have been longer, and yes, it could have been, but it’s not. I didn’t want it to be longer, I wanted to suggest a lot so that’s great. And the tempo is generated from the structure. I said to the editor Rachel Reichman, who is also the co-producer, that I was thinking about the section in The Social Network where he’s putting the website together and there’s all the cross-cutting between. I wanted it to have that kind of centrifugal force, so that was the idea.

Truffaut and Hitchcock appear to have had a genuinely close personal friendship but on an artistic level some have criticised the influence they may have had on each other. For instance the films Truffaut made immediately after the interviews are considered by some to be too Hitchcockian in style and are uneven in tone in comparison with his first three features. What are your views on this?

|

Fahrenheit 451 (1966) |

Well, you’re not going to get me to say that Fahrenheit 451 or The Soft Skin are uneven, that’s for sure. I think Fahrenheit 451 is a genuinely great film. It’s awkward, but it’s great, and the awkwardness of it is part of the greatness of it. It is actually very much in tune with what the film is about. And I’ve seen it again recently. It’s a film that I’ve always loved and I find it very moving. Soft Skin is, I think, a pretty tremendous movie. Mississippi Mermaid is very good too – it’s a little bit unwieldy, but it’s very good. The Bride Wore Black is perhaps a lesser film. But, I mean, after that I don’t think you can see much influence. In The Last Metro there are a couple of things, but I think a film, for instance, like The Woman Next Door is actually quite different from Hitchcock. Truffaut is a much more troubling, very troubling artist. There’s something deeply, deeply unsettling about his movies that has become more so now. I think that when he was alive there was the whole, you know, Truffaut/Godard, Lennon/McCartney thing, which was really exaggerated to create the impression that his films went down much more easily than they really did. You know, The Wild Child, The Green Room, Two English Girls, Day for Night, these are much richer and more disturbing films than they appeared at the time.

On the other hand, do you think Hitchcock might have become more self-conscious in his work after this dialogue with Truffaut? For instance, there’s a letter from Hitchcock to Truffaut in the documentary in which he wonders if he should have experimented more with character and narrative.

Yes, but I don’t think that that’s Truffaut eliciting something from him. I think that that was something that was always present, and I think it’s a very touching, human side to him. It’s a kind of doubt that he carried with him, “have I done enough? Did what I do have enough of an effect or should I have strayed from suspense and gone in another direction?” And I don’t think that’s because of Truffaut, it’s something that was always there. In the early 30s, for instance, Hitchcock wanted to produce a project with John Van Druten where he would let Van Druton work with a couple of actors for a year with a camera and just kind of explore. Van Druton didn’t want to do it, but it’s fascinating. I don’t think his work became more self-conscious after his interviews with Truffaut at all, I think that it’s just the change in acting created a different kind of focus. I think he coped with it better than other directors did. I mean he certainly did a better job of it than Otto Preminger did, that’s for sure. Frenzy is a genuinely great film. And it’s interesting, if you look at Topaz, the scene where Roscoe Lee Browne talks his way into the hotel is great and quite different. He’s got that quite stiff actor across the street watching Roscoe Lee Browne doing this unbelievable scene from a telephoto point of view.

|

Truffaut and Hitchcock, photograph by Philippe Halsman |

In undertaking the interviews Truffaut had a point to prove that Hitchcock was in his words “the greatest film director in the world”. Since the book was published Hitchcock’s reputation has grown to the point where many now believe this to be true. Why do you think there has been such a change in Hitchcock’s standing?

Well the book certainly played a part in it, that’s for sure. I mean, I would say that the book really elevated his reputation. Peter Bogdanovich makes the point in the movie that Truffaut was so celebrated as a filmmaker, and as a filmmaker from another generation and another place with a completely different approach to cinema, and here he was saying Alfred Hitchcock is the greatest filmmaker of all time. You know, that really meant something. I think it meant something as well that Godard had paid such close attention to him, and Rivette as well and Rohmer and Chabrol of course. All of them did, but the book really sits at the centre of that.

I think another way of looking at it is to consider the films themselves, which are so great that of course they’re going to outlast the judgments that were made about them at the time. It’s hard to imagine that not happening.

Interview by Simon Hitchman, © March 2016 - please do not reprint or reuse without permission. |