|

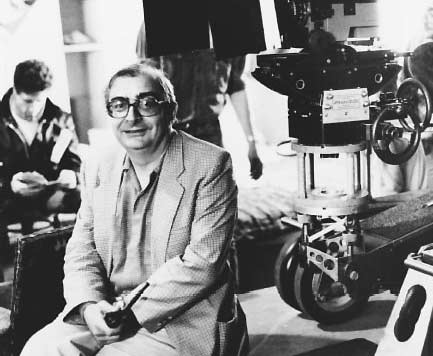

Claude Chabrol by Guy Austin

A comprehensive study of the great director’s films, the development of his style and an exploration of his work’s theoretical and political resonance.

Explore this book:

|

In a career lasting over fifty years, Claude Chabrol (24 June 1930 - 12 Sep 2010) was one of the most prolific and widely respected of French film directors. As one of the prime instigators of the French New Wave, Chabrol’s early features helped to establish the movement as a vital new force in cinema. From the late 1960’s onwards, Chabrol began making the suspenseful psychological thrillers, including La Femme Infidele (1968) and Le Boucher (1969) , for which he is best known. |

|

|

Dir. Claude Chabrola

|

|

Born in Paris in 1930, into a comfortable middle-class family, Chabrol was evacuated during the war to the isolated rural village of Sardent in central France. Already a film enthusiast, he set up a makeshift cinema in a barn where he projected German genre films, which he advertised as American “super-productions”.

After the Liberation, he returned to Paris, where he studied first pharmacology, then Law, while, at the same time, immersing himself in the thriving cine-club scene. At the Cinematheque Francais, he met Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette and Eric Rohmer, and was soon invited to write articles for Cahiers du Cinema. A devoted fan of Fritz Lang and Alfred Hitchcock, he collaborated on a book about Hitchcock with Rohmer which became the first serious study of “the master of suspense”.

Backed with money inherited by his wife, Chabrol wrote, produced and directed Le Beau Serge in 1958, a film often cited as the first New Wave feature. Shot over nine weeks in Sardent, using natural light and real locations, the film portrays a detailed picture of working class life in a bleak provincial village. Reflecting the influence of both Rossellini and Hitchcock, the film plays on the theme of “the double”, with it’s two young protagonists, Francois (Jean-Claude Brialy) and Serge (Gerard Blain), mirror opposites locked in a power struggle. Le Beau Serge was well-received, winning an award at the Locarno film festival, and a lump sum of money from the Film Aid board, which enabled Chabrol to start production on his next film before the first had been released to the public.

Les Cousins (1959) again featured actors Gerard Blain and Jean-Claude Brialy, as a pair of polar opposites, in a plot that effectively reverses the action of the earlier film. This time Blain plays the outsider, a visitor from the country to Paris, who struggles to find a place in his cousin’s social set, just as Brialy found it difficult to re-enter the closed world of the village in Le Beau Serge. Otherwise, however, it is hard to believe that the two films came from the same director. In contrast to the long takes and lyrical landscapes of his first film, Les Cousins is brash, fast-paced and urbane, with an undercurrant of biting satire.

Les Cousins was another critical and commercial success, earning a Best Film award at the Berlin Film Festival, and becoming France’s fifth largest box office success of 1959. Chabrol’s innovative approach to financing became a blueprint for other filmmakers to follow. Meanwhile, the production company he had set up, AJYM, was now able to support the debut films of Jacques Rivette (Paris Nous Appartient) and Eric Rohmer (Le Signe Du Lion). He also served as a technical advisor for Godard on A Bout De Souffle (1960). By using his success in this way, Chabrol was instrumental in getting the New Wave up and running; which in turn contributed to the press reports of unselfish interdependence and collaboration within the movement.

Chabrol’s next film, A Double Tour (1959), was a first excursion into the thriller genre, and displayed many of the concerns – murder, deception and obsession – that would dominate his later work. For his next film, Les Bonnes Femmes (1960), Chabrol assembled a strong female cast including Bernadette Lafont and Stephane Audran. The film, which follows the lives of four young women working in a shop in Paris, again combined documentary realism with Hitchcockian suspense. On the surface, an easy-going comedy/drama about the love-lives of four working girls, the humerous tone is soon offset by an undertone of tension. Its detailed depiction of Paris and memorably enigmatic ending, make this one of the masterworks of the Nouvelle Vague.

Neither of these pictures however were successful, foreshadowing a long period in which Chabrol struggled to recapture his earlier success. His subsequent releases, Les Godelureaux (1960), L’Oeil Du Malin (1961), Ophelia (1962), and Landru (1962), also failed to win either awards or an audience, and Chabrol found himself sidelined in favour of Truffaut, Godard and other contemporaries. After divorcing his wife to marry Stephane Audran, he even lost his production company and was forced to turn to more commercial assignments, such as Le Tigre Aime La Chair Fraiche (1965), which tended to alienate the critics even more who had praised his earlier work.

The turnaround came with Les Biches in 1968, a psychological drama involving a love triangle between two women (Stephane Audran and Jacqueline Sassard) and a man (Jean-Louis Trintignant). Described by Chabrol as “the first film which I made exactly as I wished”, the film heralded a new maturity in the director’s films. The film’s frank depiction of a lesbian relationship and the classical precision of its execution won Les Biches critical praise.

That same year, Chabrol continued in the same vein with another film about a relationship fractured by jealousy, La Femme Infidele (1968). The film again stars Audran as Helene, a woman having an affair behind the back of her husband Charles (Michel Bouquet). As discovery leads to murder, Chabrol reveals the dark and dangerous passions lurking beneath middle-class respectability.

Again and again, Chabrol would revisit similar themes, frequently featuring characters called Charles, Paul, and Helene. The next film in the “Helene cycle” was Que La Bete Meure (1969) which followed a character called Charles hunting down the hit-and-run killer of his son. This was followed by Le Boucher (1970), in which a village butcher, Popaul, courts the local schoolteacher, Helene, at the same time as a series of murders shatters the surrounding rural tranquility. While in Juste Avant La Nuit (1971), Charles is having an affair with Laura, the wife of his best friend. Accidentally killing her during violent love-making, he flees the scene of the crime and returns to his wife Helene as if nothing had happened. Although he appears to have got away with the murder, his guilt soon begins to overwhelm him.

Chabrol was now making films that were every bit as complex and personal as his heroes Fritz Lang and Alfred Hitchcock. Simple precision became the hallmark of his style. The stories usually featured a predator and a victim, with the predator often portrayed sympathetically. Working alongside frequent collaborators like writer Paul Gegauff, producer Andre Genoves, cinematographer Jean Rabier, editor Jacques Gaillard, and composer Pierre Jansen, Chabrol achieved a consistency of tone that made his films instantly recognisable. His films were also noted for the fine performances of actors like Stephane Audran, Michel Bouquet, and Jean Yann.

During the seventies and eighties, Chabrol continued his prolific output, making television films and international co-productions, and working with such well known actors such as Anthony Perkins, Orson Welles, Romy Schneider, Rod Steiger and Donald Sutherland. These pictures, often based on the work of well-known crime writers, such as Jean-Patrick Manchette, Ed McBain, Georges Simenon, and Patricia Highsmith, varied in quality, with some critics noting that they lacked the acute sense of place and atmosphere that had given his earlier films such resonance.

Chabrol’s best received films during this period were those featuring the actress Isabelle Huppert. Their first collaboration, Violette Noziere (1978), was based on the true story of a 19 year old girl who was convicted of poisoning her father and attempting to kill her mother. The young Huppert gave an exceptional performance, winning the best actress award at Cannes. Ten years later, they worked together again on Une Affaire de Femmes (1988), a story of abortion and retribution during the Occupation. This sympathetic portrait of an outwardly unlikeable woman drew much international acclaim.

In the 90’s they worked together again on an adaptation of Madame Bovary (1991), and then in 1995 came La Ceremonie, based on the novel Judgement in Stone by Ruth Rendell. The story of a disturbed young woman who turns on the family who hire her as a maid was prime Chabrol material, and he successfully translated it into one of his most powerful thrillers. Sensational performances from Huppert, Sandrine Bonnaire, and Jacqueline Bisset, and its shocking climax made the film an international hit, leading to reappraisal of the man dubbed “The French Hitchcock”.

In his seventies, Chabrol continued making provocative, absorbing films, seemingly unaffected by the tides of fashion. Two of the most successful were Merci pour le chocolat (2000) and La Fille coupée en deux (A Girl Cut In Two, 2007). His final film was Bellamy (2009) starring Gérard Depardieu.

On 12th September 2010, Claude Chabrol died, aged 80. Among the many tributes paid to him was a statement from the French film directors’ association: “Every time a film-maker dies, a singular view of the world and a particular expression of our humanity is irreparably lost to us.”

AS DIRECTOR:

Le Beau Serge (Beautiful Serge) (1958)

Les Cousins (The Cousins) (1959)

À Double Tour (1959)

Les Bonnes Femmes (The Good Girls) (1960)

Les Godelureaux (Wise Guys) (1961)

Les Sept Péchés capitaux (sketch) (1962)

L'Oeil du Malin (The Third Lover) (1962)

Ophelia (1963)

Landru (Bluebeard) (1963)

Les plus belles escroqueries du monde (sketch) (1964)

Le Tigre aime la chair fraiche (The Tiger Likes Fresh Blood) (1964)

Paris vu par... (sketch) (1965)

Marie-Chantal contre docteur Kha (1965)

Le Tigre se parfume à la dynamite (An Orchid for the Tiger) (1965)

La Ligne de démarcation (Line of Demarcation) (1966)

Le Scandale (The Champagne Murders) (1967)

La Route de Corinthe (The Road to Corinth) (1967)

Les Biches (The Does) (1968)

La Femme infidèle (The Unfaithful Wife) (1969)

Que la bête meure (The Beast Must Die) (1969)

Le Boucher (The Butcher) (1970)

La Rupture (The Breach) (1970)

La Décade prodigieuse (Ten Days Wonder) (1971)

Docteur Popaul (Dr Popaul) (1972)

Les Noces rouges (Wedding in Blood) (1973)

Nada (1974)

Une Partie de plaisir (Pleasure Party) (1975)

Les Innocents aux mains sales (Innocents with Dirty Hands) (1975)

Les Magiciens (Death Rite) (1976)

Folies bourgeoises (The Twist) (1976)

Alice ou la Dernière Fugue (Alice or the Last Escapade) (1977)

Les Liens de sang (Blood Relatives) (1978)

Violette Nozière (Violette) (1978)

Histoires Insolites (TV) (1979)

Fantomas (TV) (1980)

Le Cheval d'orgueil (The Horse of Pride) (1980)

Le Systeme du Docteur Goudron at du Porfesseur Plume (TV) (1981)

Les Fantômes du chapelier (1982)

Le Sang des autres (The Blood of Others) (1984)

Poulet au vinaigre (Cop Au Vin) (1985)

Inspecteur Lavardin (1986)

Masques (1987)

Le Cri du hibou (The Cry of the Owl) (1988)

Une Affaire de femmes (A Story of Women) (1989)

Jours tranquilles à Clichy (Quiet Days in Clichy) (1990)

Docteur M (1990)

Madame Bovary (1991)

Betty (1992)

L'Œil de Vichy (The Eye of Vichy) (1993)

L'Enfer (Hell) (1994)

La Cérémonie (1995)

Rien ne va plus (1997)

Merci pour le chocolat (2000)

La Fleur du Mal (2002)

La Demoiselle d'honneur (The Bridesmaid) (2004)

L'Ivresse du pouvoir (The Comedy of Power) (2006)

La fille coupée en deux (The Girl Cut in Two) (2007)

Bellamy (2009)

|

|

CLAUDE CHABROL POSTER GALLERY |

Coming Soon!

|