|

|

Want to get into the new wave, but feeling a bit overwhelmed? We'll take you for a quick spin through the basics...

FRENCH NEW WAVE: WHERE TO START © 2008 Simon Hitchman |

1. What is the French New Wave, anyway?

The Nouvelle Vague: A Beginner's Guide

The directors associated with the Nouvelle Vague, including Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, Louis Malle, Alain Resnais, Agnes Varda and Jacques Demy have made, between them, films numbering in the many hundreds. (For reference, you can see the New Wave Encyclopedia for films we consider to be a part of the French New Wave.) If you were to add to this the works of those various filmmakers of the era who have been labelled as New Wave at one time or another, as well as those influenced by the movement, both in France and abroad, then the number of potential films would run into the thousands.

Getting to grips with the New Wave might understandably therefore seem a daunting prospect for somebody wanting to explore the movement for the first time. With that in mind, this introduction will provide some general context and a brief overview of some of the characteristics associated with the French New Wave. It will also offer some suggestions about where to start your investigations, as well as an overview of the seminal "must see" films which best define the movement. If you’ve already seen many of the best known New Wave films, or are looking for a more specific approach, you might try our Top 10 New Wave Film Lists, which drill down by director, sub-genre, performance and various other categories.

Fifty years on: Why the New Wave Still Matters

It has now been more than half a century since the directors of the New Wave (in French, "Nouvelle Vague") electrified the international film scene with their revolutionary new way of telling stories on film. The New Wave itself may no longer be "new", but the directors and their films are still important. They are the progenitors of what we have come to think of as alternative cinema today, and they had, and continue to have, a profound influence on cinema and popular culture throughout the world. Without the Nouvelle Vague there may not have been any Scorsese, Soderbergh, or Tarantino (or Forman, or Wenders, or Bertolucci), and music, fashion and advertising would be without a major point of reference.

The directors of the Nouvelle Vague, and those of their like-minded contemporaries in other countries, created a new cinematic style, using breakthrough techniques and a fresh approach to storytelling that could express complex ideas while still being both direct and emotionally engaging. Crucially, these filmmakers also proved that they didn't need the mainstream studios to produce successful films on their own terms. By emphasizing the personal and artistic vision of film over its worth as a commercial product, the Nouvelle Vague set an example that inspired others across the world. In every sense they were the true founders of modern independent film and to watch them for the first time is to rediscover cinema.

A Radical New Type of Filmmaking

To get a general idea of what this new cinematic approach meant, it might help to understand that before they were directors, the main players of the New Wave were the original film geeks or cinephiles. Cinema was very important in culture-starved post-war France, and most of the New Wave directors spent a great deal of time in their early years writing or thinking about it. Some were film critics, some were simply lovers of film - nearly all sharpened their cinematic sensibilities through long hours spent in the various Parisian cinematheques and film clubs. Their influences included everything from movies by realist Italian directors like Roberto Rosselini to hard-boiled Noir and B movies from America, as well as early silent classics and even the latest technicolour Hollywood musicals. From this passion for cinema they developed a belief in the theory of the auteur: that is, a conviction that the best films are the product of a personal artistic expression and should bear the stamp of personal authorship, much as great works of literature bear the stamp of the writer.

Une Femme Est Une Femme, dir. Jean-Luc Godard [1961] .

|

Although they admired many of the studio films being made at the time, they also felt that most mainsteam cinema, especially in France, was not expressing human life, thought, and emotion in a genuine way. Many of the popular movies of the era, they argued, were dry, recycled, inexpressive and out of touch with the daily lives of post-war French youth.

While the Nouvelle Vague may never have been a formally organized movement, its filmmakers were linked by their self-conscious rejection of the "cinéma de qualité" ("cinema of quality"), the studio-bound, script-centered cinema that dominated the French filmscape at the time. Besides being made to impress rather than express, these films generally afforded their directors very little freedom or creative control, instead catering to the commercial whims of producers and the influence of screenwriters. Those New Wave directors who started as critics, mainly writing for the French journal called Cahiers du Cinema, regularly praised the films they loved and tore apart those films they hated in print. Through the process of judging the art of cinema, they began to think about what it was that might make the medium special. More importantly they were gradually inspired to begin making films themselves. While each director had a slightly different agenda, Truffaut could be said to encapsulate the group's mission when he said, "The film of tomorrow will not be directed by civil servants of the camera, but by artists for whom shooting a film constitutes a wonderful and thrilling adventure."

Broadly speaking, the New Wave rejected the idea of a traditional story in the "Old Hollywood" sense of stories based on narrative styles and structures lifted from earlier media, namely books and theatre. The New Wave directors did not want to hold your hand through each scene, directing you emotion by emotion, through a fixed narrative. There was a feeling that this sort of storytelling interfered with the viewer's ability to perceive and react to film just as they would perceive and react to life. These directors wanted to break up the filmic experience, to make it fresh and exciting, and to jolt the moviegoer out of complacent viewing - to make the viewer think and feel, not only about what they were watching, but about their own lives, thoughts and emotions as well. Dialogue was to be as realistic and spontaneous as possible, or philosophical in a way that made one think beyond the film. Expressing the truth was of the utmost importance. The object was not simply to entertain, it was to sincerely communicate.

The scripts (or lack thereof) of these new directors were often revolutionary, but the films' modest budgets often forced them to become technically inventive as well. As a result, the movies of the Nouvelle Vague have became known for certain stylistic innovations such as: jump cuts (a non-naturalistic edit), rapid editing, shooting outdoors and on location, natural lighting, improvised dialogue and plotting, direct sound recording (as opposed to the dubbing that was popular at the time), mobile cameras, and long takes. In addition, their films often engaged, although sometimes indirectly, with the social and political upheavals of their times. You can read a more in-depth history of the French New Wave in our history article.

New Wave International

The Firemen's Ball, dir. Czech New Wave director Milos Forman [1967] .

|

Although the French New Wave is the best known, similar cinematic movements were happening elsewhere, also fuelled by the cultural and social change that came in the wake of the Second World War. In Britain, the emergence of the Free Cinema movement in the 1950’s paralleled the course of the French New Wave. The first productions of these filmmakers, who included Lindsay Anderson, Tony Richardson and Karel Reisz, were documentaries chronicling working-class life that had a freshness, energy and modern satirical edge. These qualities were also characteristic of their subsequent feature films, many of which were adapted from the plays and novels of the so called “Angry Young Men” writers.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in Europe, the French and British New Waves inspired groups of like-minded young directors in Communist-controlled Czechoslovakia (Milos Forman, Vera Chytilova , Ivan Passer) and Poland (Roman Polanski, Jerzy Skolimowski). Shooting on location, often using non-professional actors, they sought to capture life as it was really lived in their societies. In Italy too, young directors making their first films such as Bernardo Bertolucci and Marco Bellocchio were directly inspired by the Nouvelle Vague. The same was true of a new generation of German directors, including Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Wim Wenders and Werner Herzog, who emerged at the end of the 1960s and came to be known as the New German Cinema.

Revolutionary film movements also arose in Japan and Brazil where directors like Nagisa Oshima and Glauber Rocha made films devoted to questioning, analyzing, critiquing and upsetting social conventions. Indeed, in countries around the world, young filmmakers armed with hand-held cameras and ideas inspired by the Nouvelle Vague were making films on their own terms. All had their own particular flavour, but in each case, came into being as a reaction against what had come before and arose out of the feeling that such breaks in tradition were necessary to the positive evolution of cinema in their country.

Pulp Fiction, dir. Quentin Tarantino [1994] .

|

Even the United States, the very heartland of commercial cinema, had its own New Wave lead by actor turned filmmaker John Cassavetes, who blazed a trail for independent American cinema with films like Shadows (1959) and Faces (1968), which bore remarkable similarities to the work of the French New Wave. Equally groundbreaking was the work of the Direct Cinema documentary movement lead by Richard Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker and the Maysles brothers who applied similar techniques to the New Wave and the French Cinema Verité filmmakers in an effort to directly capture reality and represent it truthfully.

The Nouvelle Vague would also be acknowledged as a major inspiration on the New Hollywood generation of directors such as Arthur Penn, Francis Ford Coppola, Robert Altman and Martin Scorsese. This influence has continued to the present day with many of the major figures in contemporary independent American cinema, including Steven Soderbergh, Quentin Tarantino, and Wes Anderson, professing admiration for the movement and employing many of its techniques. As Scorsese himself put it: "the French New Wave has influenced all filmmakers who have worked since, whether they saw the films or not. It submerged cinema like a tidal wave".

|

2. What are the best films for beginners?

The films below are meant as a beginner's guide to some of the best known work of the French New Wave by directors in the Cahiers group, Left Bank group, and others in France who were associated with the movement, made from the early 1960s through the early 1970s. There are many other films associated with the movement. For our complete list of French New Wave films, you can see our Films Encyclopedia. And for more in-depth lists of recommended movies, take a look at our Top 10 French Film lists. International films and film lists will be coming soon.

The Cahiers du Cinema Directors

Although opinions differ as to which directors belong in the Nouvelle Vague and which don’t, all are agreed that the five directors (Claude Chabrol, Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette) who wrote for Cahiers du Cinema, are the core of the movement. The following is a selection of key films by those directors which helped define the New Wave during its heyday.

|

Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows, 1959) Francois Truffaut

This smash hit of the 1959 Cannes Film Festival may not have technically been the first New Wave movie, but it was the first to gain widespread attention and is often cited as the real beginning of the Nouvelle Vague. Truffaut drew on inspiration from his own troubled childhood for this classic story of youthful rebellion. |

|

|

|

À Bout De Souffle (Breathless, 1960) Jean-Luc Godard

In one of the most audacious directorial debuts in film history, Godard redefines the rules of cinematic storytelling in this thrilling homage to American gangster flicks which made a star of Jean-Paul Belmondo and continues to influence film and fashion. |

|

|

|

Tirez Sur Le Pianiste (Shoot the Piano Player, 1960) Francois Truffaut

Comedy and tragedy go hand in hand in Truffaut’s eloquent and playful homage to Film Noir. In the lead role Charles Aznavour is brilliant as Charlie, the washed up pianist, who is forced to face up to the past he has tried to forget, when his gangster brother comes to the bar where he works one night. |

|

|

|

Les Bonnes Femmes (The Good Girls, 1960) Claude Chabrol

New Wave realism meets Hitchcockian suspense in this compelling drama chronicling the lives and loves of four Parisian shop girls over the course of several days. The unsentimental portrayal of contemporary young women proved too distressing for some and the film provoked a backlash which saw Chabrol retreat into more escapist material until the late 60s. |

|

|

|

Jules et Jim (Jules and Jim, 1962) Francois Truffaut

Truffaut’s enduring masterpiece is a captivating story of love and friendship between three people over the course of twenty-five years. A stylistically thrilling work of cinema, brimming with charm, full of innovative storytelling techniques, and running the gamut of emotions, from joie de vivre to tragedy. |

|

|

|

Vivre Sa Vie (My Life to Live, 1962) Jean-Luc Godard

Twelve Brechtian tableaux chronicle the life and death of a young woman, beginning as a cinema verite documentary and ending as a Monogram style B movie. A fierce critique of consumerism in which people become just another commodity to be bought and sold. |

|

|

|

Le Mépris (Contempt, 1963) Jean-Luc Godard

Brigitte Bardot gives one of her best performances in Godard’s emotionally raw account of a marital break up set against the intrigues of the international film industry. With its beautiful soundtrack by Georges Delarue, and sumptuous Mediterranean colours, it has the weight and resonance of classical tragedy. |

|

|

|

Bande à Part (Band of Outlaws, 1964) Jean-Luc Godard

Anna Karina teams up with a couple of petty crooks played by Sami Frey and Claude Brasseur in this freewheeling crime caper thriller set in and around the streets of Paris. This is one of Godard’s most playful movies, full of off the cuff invention and memorable set pieces. |

|

|

|

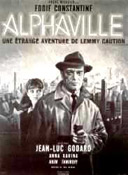

Alphaville (1965) Jean-Luc Godard

Science-fiction and film noir collide in the bizarre city of Alphaville where free thought and individualist concepts like love, poetry, and emotion have been eliminated. Can secret agent Lemmy Caution fulfil his mission to kill Professor Von Braun and destroy the evil computer Alpha 60? |

|

|

|

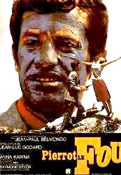

Pierrot le Fou (1965) Jean-Luc Godard

One of Godard’s greatest achievements, this pulp-noir anti-thriller has been described as cinematic Cubism Shot in dazzling primary colours and loaded with references to literature, painting, other movies and pop culture, Pierrot Le Fou is, amongst other things, about the struggles of the artist, Vietnam, and the death of romance. |

|

|

|

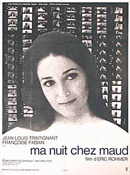

Ma Nuit Chez Maud (My Night With Maud, 1969) Eric Rohmer

A brilliantly insightful and sublime meditation on adult indiscretions. Jean-Louis Trintignant plays a chaste engineer who believes he has found his perfect woman, yet finds his certainty challenged while accidentally spending a night with the intelligent and seductive Maud. |

|

|

|

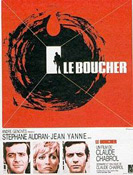

Le Boucher (The Butcher, 1970) Claude Chabrol

A village schoolteacher begins to suspect that her close friend, the local butcher, might enjoy carving up more than steak and porkchops. Widely considered Chabrol's greatest work, this Hitchcock-inspired thriller is rich in both authentic atmosphere and nerve-jangling suspense. |

|

|

Although the Cahiers du Cinema directors became the most celebrated members of the Nouvelle Vague, another loose contingent of brilliant and highly original filmmakers were also associated with the movement. This was the Rive Gauche or Left Bank Movement whose core members included Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Agnes Varda. These filmmakers had backgrounds in documentary and literature, an interest in experimental storytelling, and an identification with the political left. (Although it is worth noting that the label "Left Bank" was constructed by journalists years after the fact. At the time the friends did not consider themselves part of any group). Other associates of the movement included Alain Robbe-Grillet, Marguerite Duras, Henri Colpi, and, by virtue of his marriage to Agnes Varda, Jacques Demy. The following is a selection of films to watch by this group made during the New Wave era. For more suggestions visit our Top 10 Lists and the French New Wave Encyclopedia.

|

Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) Alain Resnais

An intense love affair between a French actress and a Japanese architect in postwar Hiroshima leads to painful revelations about past love and wartime suffering. A highly original and visually stunning masterwork from Resnais. |

|

|

|

Lola (1961) Jacques Demy

Jacques Demy’s auspicious debut is “a musical without music” set in the port city of Nantes, and staring Anouk Aimee as the title character, a cabaret singer awaiting the return of her long-absent lover from overseas. Meanwhile she is being courted by a childhood friend and an American sailor. Will she wait for her true love or settle down to a new life... |

|

|

|

L’Année Derniere à Marienbad (Last Year at Marienbad, 1961) Alain Resnais

A complex cinematic mystery story that breaks all the rules of traditional narrative film-making. In it, a man meets a woman who he may or may not have had an affair with many years before. Watch carefully and make up your own mind... |

|

|

|

Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cleo from 5 to 7, 1962) Agnes Varda

Cleo, a beautiful singer, anxiously awaits the results of a medical exam. For 90 minutes, in real time and across real geography, the film follows her as she walks through Paris, meets with friends, returns home to a rehearsal with musicians, and begins to feel overwhelmed by her thoughts and her fear. She finally meets a soldier on leave from the war in Algeria who shares her fear of imminent death. |

|

|

|

La Jetée (The Pier, 1962) Chris Marker

In a post-apocalyptical world a man is chosen to undergo a time-travel experiment by virtue of his one enduring childhood memory: a woman’s face at the end of the pier at Orly airport. Once seen this unique film is never forgotten. The inspiration for Terry Gilliam's Twelve Monkeys. |

|

|

|

Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, 1964) Jacques Demy

A wistfully melancholic love story in which every line of dialogue is sung. This romantic musical is the perfect introduction to the enchanting world of Jacques Demy. If you like this,try the equally enchanting Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (The Young Girls of Rochefort) |

|

|

Before the phrase was ever invented, there was in fact already a "new wave" of directors in France breaking with the traditional modes of production and setting an example that others would follow. Although vastly different in both content and style, the films of directors such as Jean-Pierre Melville, Jean Rouch, Louis Malle and Alexandre Astruc were visionary and innovative. Later these directors became associated with the Nouvelle Vague movement, although some of them, such as Jean-Pierre Melville, rejected the label.

After the New Wave became a success, a whole new generation of filmmakers in France were inspired to follow their example. Over 20 directors released their first films in 1959 and this number doubled in the following year. In 1962, a special edition of Cahiers du Cinema was released in which 162 new French Filmmakers were listed. Inevitably many have not stood the test of time, however the best of them went on to have long and enduring careers.

What follows are some key films by these directors leading up to, during, and immediately after the Nouvelle Vague period.

|

Bob le Flambeur (Bob the Gambler, 1955) Jean-Pierre Melville

Suffused with wry humour, Melville’s film, set in a morally ambiguous world of smoky bars and late night gambling dens, melds the toughness of American gangster films with Gallic sophistication, laying a roadmap for the French New Wave to follow. |

|

|

|

Et Dieu... Créa la Femme (And God Created Woman, 1956) Roger Vadim

Vadim’s directorial debut broke box office records and censorship taboos in its teasing display of sex and eroticism in Saint-Tropez. Its success lauched the career of Brigitte Bardot and gave independent producers the confidence to back the up-coming films of the New Wave |

|

|

|

Ascenseur Pour l'Échafaud (Elevator to the Gallows, 1958) Louis Malle

In his debut feature, Louis Malle captures the beauty of Jeanne Moreau, the brilliant camerawork of Henri Decae, and the musical genius of Miles Davis in a tightly constructed film noir.] |

|

|

|

Les Yeux sans Visage (Eyes Without a Face, 1960) Georges Franju

Secluded in the French contryside, a brilliant, obsessive doctor attempts a radical plastic surgery to restore the beauty of his daughter’s disfigured face, but at a horrifying price. Franju’s lyrical horror film has become a classic of the genre. |

|

|

|

Adieu Philippine (Goodbye Phillipine, 1962) Jacques Rozier

As a young man awaits his army call-up he begins a romance with two girls who are close friends. This beautifully shot ode to lost innocence is one of the quintessential works of the Nouvelle Vague. |

|

|

|

Le Feu Follet (The Fire Within, 1963) Louis Malle

A melancholic study of a self-destructive writer who resolves to kill himself and spends the next twenty-four hours trying to reconnect with a host of wayward friends. Maurice Ronet gives an outstanding performance as Alain who has spent his life “waiting for something to happen”, but refuses to accept the compromises of adulthood. |

|

|

|

Un Homme et une Femme (A Man and a Woman,1966) Claude Lelouch

Claude Lelouch scored an award-winning international hit with this eloquent love story which became famous for it’s lush visuals, the performances of its two leads Anouk Aimee and Jean-Louis Trintignant, and its unforgetable musical theme. |

|

|

|

Le Samourai (1967) Jean-Pierre Melville

Alain Delon is the ultimate existential loner in Jean-Pierre Melville’s ultra-cool crime classic. Combining 1940s American gangster films and 1960’s French pop culture with Japanese warrior philosophy, Melville’s hip, stylish thriller has often been imitated but never bettered. |

|

|

|

|

|