|

Serge Toubiana |

Serge Toubiana has been at the centre of French cinema culture for over forty years. He was co-editor of Cahiers du cinema with Serge Daney from 1973 to 1981, and then its editor from 1981 to 1991. In 2003 he took over the directorship of the Cinémathèque Francaise, a position he held until 2015. He is the co-author of Truffaut: A Biography and the co-director of the documentary Francois Truffaut: Stolen Portraits.

Ahead of the release in cinemas of the documentary Hitchcock/Truffaut, for which he co-wrote the screenplay, newwavefilm.com spoke to M. Toubiana about the film and his friendship with Francois Truffaut.

(Special thanks to The French Institute in London for arranging this interview. The Cine Lumiere often screens French New Wave films

as part of their regular programme.)

How did you become involved in co-writing the script for Hitchcock/Truffaut?

|

Truffaut, Hitchcock and Helen Scott, photo by Philippe Halsman |

Maybe two years ago the French producer Olivier Mille asked me if I could help with the project. It was supposed to be made by an American filmmaker named Gail Levin. She worked on the project in New York and I worked in Paris, but then she died – suddenly she died. After that I said to my French producer that he should co-produce the documentary with Cohen Media because I know Charles Cohen. And Charles Cohen had the idea of Kent Jones to direct the film. I’ve known Kent for a long time, since I was the Cahiers du cinéma editor. Kent is very nice, and he’s very involved in French cinema, and close to Scorcese, and so on.

So I wrote the project because my point of view is very specific because I am the guy who found the tapes a long time ago. It was in 1992. I was making a documentary on Truffaut at the time and I was working in the archives of Truffaut’s office in Les Films du Carrosse with a friend Michel Pascal who co-directed the documentary: Francois Truffaut: Stolen Portraits. I was looking in the archives and I found a big box and I opened it and we saw many reel-to-reel tapes. We put one of the reels on the Nagra and suddenly the voice of Hitchcock was there. It was a miracle, you know. These were the tapes from the famous dialogue between Truffaut and Hitchcock in August 1962 in Universal Studios in Hitchcock’s bungalow. And we had the voices, the three voices: Truffaut’s voice in French, Hitchcock speaking English and Helen Scott who translated, and it was incredible material. We put just a very small extract in the movie we did at the time, and after that it was finished.

Then several years after – I think it was in 1999 – I went back to Films de Carrosse to speak to Madaleine Morgenstern, who was Truffaut’s wife; she was in charge of Films du Carrosse at the time. It was the centenary of Hitchcock and I told Madaleine we have to make something with this material. So with a very good friend of mine, Nicolas Sadaa, who was in Cahiers du cinéma when he was twenty with me, and who knows Hitchcock movies very well; he and I presented twenty-five episodes of the Hitchcock/Truffaut dialogue. We put it on the air on France Culture, which is a very famous radio program, every morning at 8.30. Half hour programs of this dialogue, and they put it on two times in the afternoon. And it was a huge success. There were a lot of cinephiles who discovered the dialogue, the real dialogue between Hitchcock and Truffaut, with the voice of Hitchcock, the voice of Truffaut, and the translation made by Helen Scott. And now if you go to the internet you can find the twenty-five episodes, and these twenty-five episodes are only part of all the material which is fifty hours of dialogue. We just put on half of it with a small presentation and it was very famous.

I read the book when I was very young in the 60s – the first edition in 1966 in France. You know the first edition is very special, it’s not Hitchcock/Truffaut, it’s Le Cinema selon Alfred Hitchcock. It was such an important book in my education of cinema. For me this dialogue is one of the most important moments in the story of cinema because you have a young French director who was also an important critic, Francois Truffaut, who was thirty at the time in 1962 and had just made three movies. And you had Alfred Hitchcock who was the master. And this young guy he wanted to make, as he said in the introduction, a cookbook of how Hitchcock made his career as an auteur. So it’s a dialogue between the French theory of auteurs and a Hollywood director who had never won the Oscar but who was very famous as an entertainment director but not an auteur. And Truffaut wanted to prove that Hitchcock was a master. So it’s a dialogue between French and American cinema.

Was it a culmination in a way of the argument Truffaut had been making since the publication of his article A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema in 1954 about auteurs and auteurism? A chance for him to prove his point once and for all through Hitchcock’s example?

The first time Truffaut went to New York was in 1960 to promote Tirez sur le pianiste (Shoot the Piano Player), the second film he made. While he was there he had many contacts with American critics and he was astonished and very angry because the American critics didn’t like Hitchcock. And so he decided after he came back to Paris to make a book with Hitchcock and to ask him questions, just to convince the American critics that they missed Hitchcock’s genius. And he did it, you know. At The Cinémathèque we have all the archive of Truffaut, the letters in French and English and so on. And the letter to Hitchcock is so beautiful. Have you read it?

Yes. [For reader reference, the letter can be read here.] It’s not surprising that Hitchcock was touched by it and agreed to do the interviews. And it’s clear from the letter that Truffaut already had the whole conception of what he wanted to do.

|

the cremation scene from Jules et Jim (1961) |

And [Truffaut] approached it like he was making a film, you know. He went to Brussels to see a lot of movies he hadn’t seen yet but he wanted to see. And like you he has five hundred questions. And the miracle is that Hitchcock said: “Okay, come”. He was editing The Birds, as you know, and I think he showed some scenes from the film to Truffaut because the beginning of the tapes is on The Birds. So Truffaut saw something, not the final version of the film, but an early version. And I think Truffaut showed Hitchcock Jules et Jim, because at the beginning of the dialogue Hitchcock asked some questions about the end of Jules et Jim. He was very shocked when they put the coffin in the fire because he is Catholic, but for Truffaut fire is a very important – it’s an important theme in Fahrenheit 451, Le Chambre Verte, and so on. So for Truffaut it was natural to show this, but for Hitchcock it was very shocking. So they talk about this question at the beginning of the dialogue. It’s not in the book of course, because after the interview Truffaut changed a lot. And what you hear in this dialogue and something I like very much: in the beginning Hitchcock is very reserved, but after some time he talks more openly with Truffaut and we feel that they became very close.

What do you think it was about Truffaut that he was able to get Hitchcock to speak to him in such candour and detail about his work? Others, including André Bazin, had tried to get Hitchcock to talk seriously, but it wasn’t until this interview that Hitchcock let down his guard as it were.

You know, it’s interesting about Bazin. Bazin was not convinced that Hitchcock was a great director like Truffaut was and Rohmer was and Chabrol and Godard also. And in 1954 when Hitchcock was shooting To Catch a Thief in the South of France, Bazin came to the set in the South of France to do an interview with Hitchcock.

|

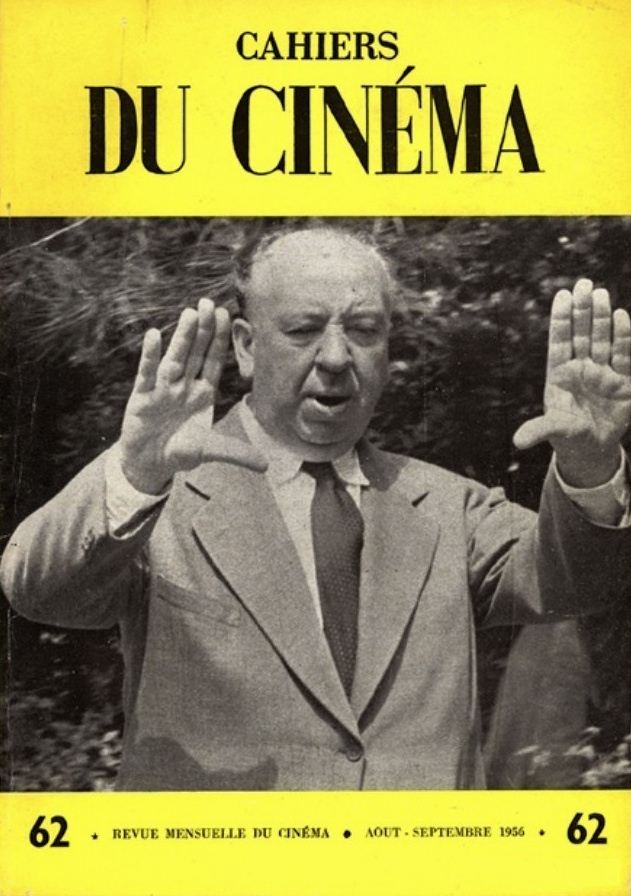

The Hitchcock 'special edition' issue of Cahiers du Cinéma |

There’s a woman who is one of the greatest script supervisors of French cinema, she is eighty-seven now, her name is Sylvette Baudrot. She was the script supervisor of all the Roman Polanski movies, Alain Resnais movies, Costa Gavras movies. One day recently she came to the Cinémathèque and she said to me, “I have letters from Truffaut I would like to give you”. And so I read the letters. Truffaut in 1954 was twenty-two, he was very young, and he had asked this woman, Sylvette Baudrot, who was script supervisor on the shooting of the Hitchcock movie and spoke English very well, to do a text for Cahiers du cinema. And so she translated the dialogue [of the interview] between André Bazin and Hitchcock, because André Bazin was not so good at speaking English. Truffaut was in charge of Cahiers du cinéma for the special Hitchcock issue and this special issue was a kind of putsch, you know. They took the power and they did it, and Bazin went to the set and he had this dialogue with Hitchcock, and [by the end] he was convinced that Hitchcock was an auteur.

After that Truffaut did an interview with Hitchcock along with Chabrol, as you know, and they became, not friends, but it was the start of their complicity. I think for their generation - Truffaut, Chabrol, Rohmer - it was obvious that Hitchcock was an auteur. He was for them, as they say in French, an inventeur du form - one of those that invented aesthetical forms like Eisenstein. But [at first] it was a big fight, because Bazin was not convinced; and there were others at Cahiers like Jacques Doniol-Valcroze who were not convinced. Pierre Kast was very aggressive against him, because for him Hitchcock was just a filmmaker and entertainer. It was a huge battle in the 50s in France, but they succeeded, and Hitchcock was very well considered by the French critics after that. But when Truffaut went to New York, he was very disappointed when he spoke to some of the most important critics. For them Hitchcock was just "the master of suspense", and that was all.

Truffaut doesn’t just listen to Hitchcock, he frequently states opinions of his own, which Hitchcock appears to listen to with great interest. Do you think that Truffaut, in a way, helped Hitchcock – the great showman known for his tongue-in-cheek sense of humour – to take himself and his own work more seriously?

|

Hitchcock directs Janet Leigh in Psycho (1960) |

No, I think no. Because Hitchcock worked in the "studio system", he had to be reserved. He had to deal with the producers, the power, so he knew very well how to manage his position in the studio system. When we listen to the tapes, Truffaut tries to talk about his ideas, but Hitchcock is very practical and he doesn't want to know. He doesn't want to have a philosophical approach to work, and he's very uncomfortable with that. At the end of the week he is more willing to talk, and the acme of the whole dialogue is on Psycho.

When Hitchcock says he is proud to have made Psycho, because he has proved that he has the power over the audience using pure cinema — it's very, very moving when you listen to the dialogue, because Hitchcock has shown he can control everything, in the look, in the eye, in the mind of the audience with this very small movie, because it was a B movie, you know. It didn't cost a lot and it was a huge success for Universal and for him also. And this moment is very, very important because we have the real Hitchcock talking about his method, his conception of mis-en-scene, and how he could control everything, second by second, because he had total control, each shot is edited to the exact frame with the music. And this film still today is so shocking, you know, the main character dying early on. But I think Hitchcock doesn't want to talk in generalities about his own work, because it's too intellectual. He preferred to be concrete and specific.

The documentary draws parallels between Hitchcock's and Truffaut’s childhood experiences of being locked up. Do you think both Hitchcock and Truffaut saw themselves as outsiders, and was that something about Hitchcock that Truffaut identified with?

Yes, of course, but Truffaut was the opposite of Hitchcock. Truffaut was a seducer; Hitchcock wanted to be one, but he couldn’t succeed – and in fact, this is very important in his movies. One of Truffaut’s theories is very good, I think, that Hitchcock had a kind of complex physically, you know, and he transformed this handicap. The sexuality is very strong in his movies; it’s obvious, but it was the French critics who were the first to see it. You know the famous sentence when Truffaut said that, “Hitchcock films scenes of love like scenes of murder, and scenes of murder like scenes of love”, which is very true. I think this kind of sensuality in the films of Hitchcock is so strong, so powerful. There is the desire, but at the same time there is also the restriction. This is the strongest idea that Truffaut and the Cahiers crew had about Hitchcock’s movies. For me this is a very, very important part of his movies. You can feel it, you know.

There are some very interesting comments in the documentary from contemporary directors who have all been influenced by the book. Most of them, however, are not directors of films one might immediately associate as Hitchcockian in style and genre. What is about the kind of cinematic language that Hitchcock created that directors working in so many different genres are able to draw inspiration from it?

|

Hitchcock's The Lodger (1927) |

I think it’s always this idea of pure cinema. You know, when Hitchcock says too many movies are just people talking, that they are like theatre not cinema. When I see movies today, most contemporary films are made with dialogue, you know, there’s nothing in terms of mise en scène, which is the way to show something to the audience with just the image and the sound, not only with the words. I think this is very important for Scorcese, for Fincher – the two who are in the documentary who say the most interesting things. It’s incredible what Scorcese says about these films, what he learned in the book from Truffaut and Hitchcock about the power of the image, you know. This is very important today. And for Truffaut and the others at Cahiers du cinema, they liked very much the English period of Hitchcock too because they recognized he wasn’t just a great director when he went to Hollywood in the 40s, he was a great director in the 30s and earlier. It’s obvious, you know. And Hitchcock talks about how he learned from silent movies to tell stories with images, you know, and how he was influenced by Fritz Lang and the first expressionist movies. And this was very important for Truffaut too. Truffaut’s obsession was to understand what was the secret of cinema, and for him the secret of cinema is in the silent movie.

The film features scenes showing the Cahiers du cinéma offices in the 1950s and reminds us how important that magazine was to the evolution and perception of cinema as an artform. As somebody who edited Cahiers for many years, do you think film criticism still has an important part to play in our understanding and appreciation of cinema?

I think so, yes. Let’s take Clint Eastwood for example. The first guy who wrote good reviews of Eastwood’s films was Olivier Assayas. He was very young and I think the film he wrote about was maybe Honkytonk Man in 1982. You are too young to remember the reviews of the early Eastwood movies, but they were very bad. For me he’s a great director, I like him very much. I like him as an actor too, but as a director his mise en scène is wonderful. But in the beginning the reviews of his films were very bad, you know, because he was a popular actor known for the Sergio Leone movies and the Don Siegel movies and so on. It was very rare to see good reviews of his movies. I met him many times, I’ve done interviews with him and he is very humble. But when you see his movies, even his westerns, they’re incredible. Incredible. So there are always some battles we have to win and to look carefully at directors like that.

The opposite of that is the tyranny of auteurs. We have to be careful because it’s too easy now to say a young director is an auteur. No, he’s not an auteur, because to be an auteur you need to make a lot of movies, but Eastwood is a very good example of how the view of a director can change. Now it’s okay to like him, but in the 70s and at the beginning of the 80s it was very hard to say good things about him because he was just an actor, you know. You like his films too?

Yes, very much. Even his first film Play Misty for Me is a very effective thriller.

Yes, it's very good.

And now he’s respected as one of the best American directors.

But in the beginning he was not considered like that because he was a popular actor and so on – he was not taken seriously.

You co-wrote what many people consider the definitive biography of Truffaut, as well as putting on an exhibition at the Cinémathèque in 2014 about his life and work. I wondered what your impressions were of him as a person – you knew him personally yourself didn’t you?

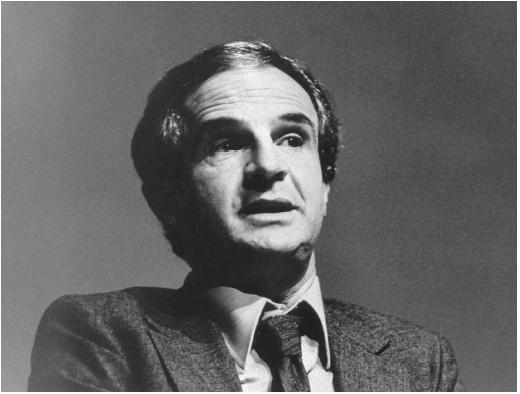

Yes, of course. I met him many times. I met him for the first time in 1975 with Serge Daney. I was very young, Serge Daney was my mentor and he was in charge of Cahiers du cinéma after the Maoist period, which was awful, you know. Truffaut was very angry against Cahiers du cinéma at the time, and I said to Daney, “Serge, we have to go and see Truffaut. We have to go and talk with him because he is part of the Cahiers du cinéma community”. Serge said, “Yes, of course, write a letter to him”. So I wrote him a letter and we both signed it and sent it to his office and his assistant gave us a call and said, “Okay, Mr Truffaut wants to see you”.

|

Francois Truffaut |

So we went to see Truffaut at his office near the Champs Elysees, and I met Truffaut for the first time. He was very shy, you know, but his look was very strong. And we said to Truffaut we would like to make a new Cahiers du cinéma and he told us, “You should create a new magazine and not use Cahiers du cinéma for publishing Maoist text on cinema because it was not the project of Andre Bazin”. So we told him what we wanted to do and he said, “Okay, you are telling me you want Cahiers to return to cinema. I am behind you, but I will remain neutral”. So we said, “Okay, thank you”. And after that we took the Metro to Bastille from Champs-Elysees, and we had nothing to say to each other. But it was very important what he said, because after that I decided with Daney to transform Cahiers du cinéma and to create a new attitude. And we did it, it took us five years, but we succeeded.

In 1980 I convinced Truffaut to give a major interview to Cahiers du cinéma, which was incredible. He came to my home, and we had all day to do the interview. In this period Godard was very aggressive against him, and he decided to answer Godard but in Cahiers du cinéma, and he said some very strong things. And this was the beginning of a new relationship between Truffaut and Cahiers. After that I met him two times a year. We had lunch when he was in Paris and became, not friends, but very close. He trusted me. He told me, “You are the most civilized critic of Cahiers du cinéma”. This was a new period for me, and at the time I loved Truffaut movies - I loved Godard films too – for me it was my culture; but at the time, because of the political views of Godard, it was difficult to like both of them – even for Daney. Daney did not like Truffaut’s movies – he preferred Godard of course.

But after I met Truffaut, he was very, very important for me, and when he died I was totally shocked because he was the first guy of the New Wave who died, and he was very young, just fifty-two. And after that I decided to make a documentary Stolen Portraits, and after that a biography, because when I went to his office after he died, his wife Madeleine allowed me to go to the archives. All the archives were there, film by film, with dossiers on Chaplin, Bresson, Renoir, Hitchcock, Gance, Rivette, Rohmer, Godard, and so on. It was kind of like La Chambre verte (The Green Room), you know, all his life was there. Les Films du Carrosse was like a protective sanctuary for him. It made me want to know the secret of this guy. And the secret, for me, was how he organized his life. Starting as a very young critic, very aggressive, very talented. Then he made his first short film Les Mistons, and after that The 400 Blows – how he constructed his strategy, you know. It’s wonderful what he did. Incredible. Then I put on the exhibition. It’s now in Frieberg in Switzerland. I came yesterday from Frieberg. And we discovered new materials, you know, letters and so on. It’s wonderful, because he kept everything, everything. And he had letters from Ray Bradbury, Jean Cocteau, Rossellini, Renoir. All his family want to give it to the Cinémathèque and it’s a treasure, you now, it’s a treasure.

Interview by Simon Hitchman, © March 2016 - please do not reprint or reuse without permission. |