|

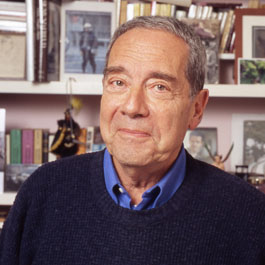

director Alain Jessua |

Alain Jessua once described himself “as a UFO” in the French cinema of his time. Commercially and critically successful, though neither mainstream nor avant-garde, Jessua is a maverick whose work, like that of the great American maverick director Samuel Fuller, explores controversial subjects in a bold, cinematic style.

However, unlike Fuller, his career has yet to receive the kind of reassessment and serious study it deserves, and, as a result, his compelling and highly-original films, which include La Vie à L’envers (Life Upside Down, 1964), Jeu de massacre (The Killing Game, 1967), Traitement du choc (Shock Treatment, 1973), Les Chiens (The Dogs, 1979) and Paradis pour tous (Paradise For All, 1982), are rarely screened and largely unavailable on English-subtitled DVD.

Recently Monsieur Jessua kindly agreed to the following rare and exclusive interview with newwavefilm.com in which he talks about his remarkable life in cinema.

>> Read Alain Jessua's biography.

Can you tell me about your early years?

I was born in Paris. World War II had a strong presence throughout my childhood since I was seven at the onset of the war and eleven when Paris was liberated. I come from a Jewish family so we had to flee and hide during the occupation. We stayed with friends who saved our lives.

Did you have an interest in the cinema as a child?

Yes, when I was little some of my friends had small film projectors and we used to watch silent films like Metropolis (1927). It was my first initiation to cinema.

At what point did you decide to become a filmmaker yourself?

After the war, one of my friends and I - he was the nephew of film director Julien Duvivier - would sneak on to Duvivier’s film sets and watch him and his crew at work. That’s when I decided to become a filmmaker. To me, the film studios were factories manufacturing dreams. I loved the smells on set and the atmosphere really fascinated me.

Did you go to film school?

When I finished school I had the option of either going to film school, which weren’t well regarded at the time, or starting work experience on film sets. I choose the latter.

You worked for Jacques Becker and Max Ophuls as an assistant. What did you learn from them?

|

Casque d'Or (1952) |

The first film I worked on was Casque d’Or (1952) by Jacques Becker. I was seventh assistant, meaning that I did all the menial work, but I learnt a lot through observation. In fact, that’s how I learnt to be of a film director; I learnt on the job.

It was amazing to experience Becker’s passion for cinema. He loved his art but worked really slowly. He had been working on Casque d’Or for ten years and the producers threatened to withdraw funding if he did not speed things up, so it was interesting to see him come to grips with this financial pressure. The way Becker directed actors was very different from the way Ophuls directed them. Becker was very detail-oriented and loved playing with the actors’ intonation. He would make them say the same line with ten different intonations resulting in ten different meanings.

I was very lucky to be given the opportunity to become Max Ophuls’ second assistant on Madame de... (1953). Max Ophuls’s way of directing was rather distinctive: before shooting a scene, the actors would rehearse on set without the rest of the film crew, which was a very modern way of doing things. Working on the film, I was able to follow all the final stages of production, including dubbing and editing, which was an amazing experience.

Cinema was very hierarchical then; it was almost like being in the army. I was fortunate Becker and Ophuls were very open-minded. They liked sharing ideas with assistants and worked closely with them. My films are at loggerheads with Ophuls’s but he remains the strongest influence on my work.

|

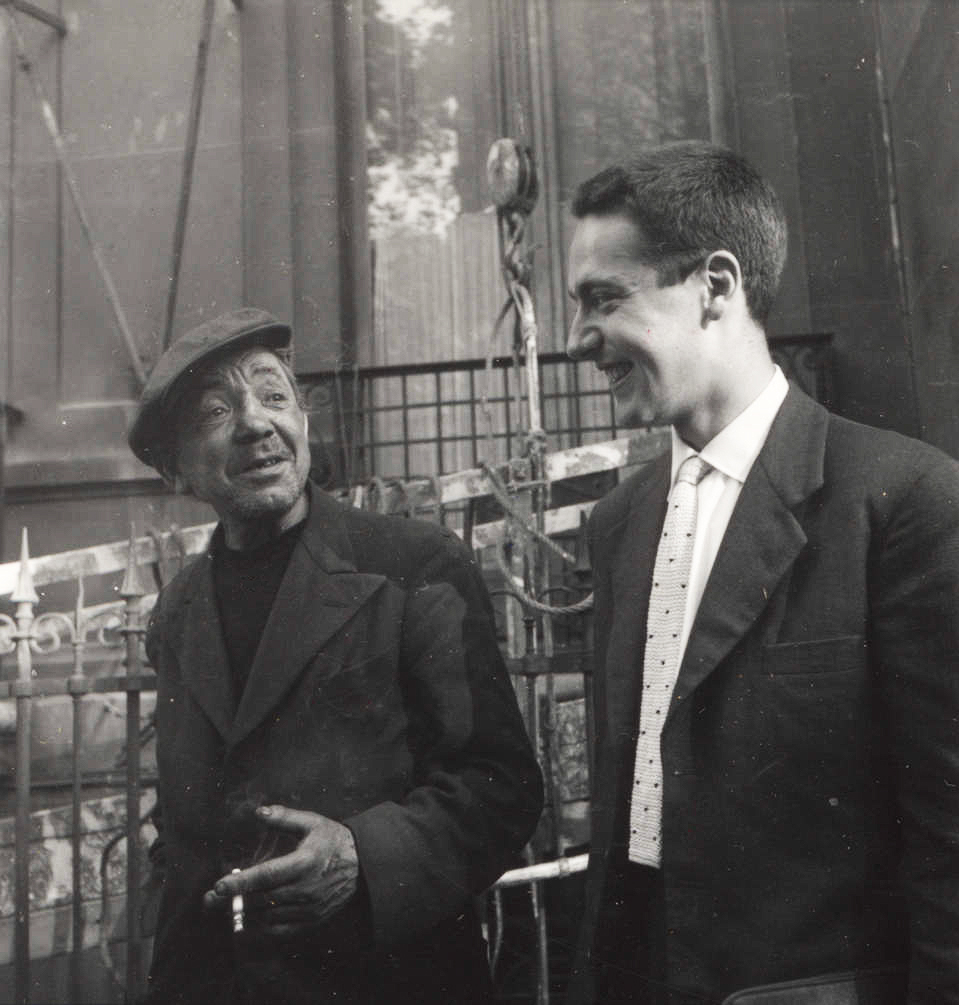

The tramp Leon Boudeville and a young Alain Jessua, 1956 |

Your first short film was Léon la Lune (1956) about a day and night in the life of a tramp. Can you tell me how the film came about?

One day, while I was on set doing some assistant work, it suddenly occurred to me that I was becoming a film technician and that was not my goal when I started working in cinema. That was my wakeup call. That’s when I decided to make a short film.

It so happened that I was in a severe car crash, while working on an Yves Allegret film (Mam'zelle Nitouche, 1954), and I was immobilized for a while. Luckily I had subscribed to a life insurance a couple of days before the accident so I used the compensation to fund my first short film.

Léon la Lune’s story is based on the real lives of tramps at the time. Some of them chose to live on the margins of society and in loneliness; it was a lifestyle.

You collaborated with the poet Robert Giraud on the film – what was it like to work with him?

Robert Giraud was a specialist of the unusual Paris. He lived at night and he actually introduced me to the tramp starring in the film. He was a real fountain of knowledge when it came to the Parisian underbelly.

The film won the Prix Jean Vigo in 1957. It must have given you quite a lot of confidence to win an award for your first film.

Yes to a certain extent but not exactly. Filmmaking has never been an easy process for me. I have never felt I should rest on my laurels. In fact, I was not able to make another short film after Léon la Lune. What the film gave me though, was the possibility to dedicate more time to scriptwriting. I still did some work for the likes of Marcel Carné but with the success of Léon la Lune and funding from the Malraux legislation (1962) that supported filmmakers I was able to write my first feature length film.

There were seven years between Léon La Lune and your first full-length film. In that time the Nouvelle Vague came to prominence. Did you feel part of the movement or separate from it?

Prior to the Nouvelle Vague, you needed more than ten years of experience as an assistant to contemplate the prospect of directing a full-length film. Most first time film directors were in their forties so French cinema was starting to feel rather arthritic. Since the Nouvelle Vague filmmakers were usually 25 to 30 years old, people came to realize younger film directors were perfectly able to make good films with smaller budgets and more freedom.

I never really felt part of the Nouvelle Vague. I befriended some of its prominent proponents but I never identified with the movement. I think its most important contribution to cinema was the revolution in film editing that Jean Luc Godard brought about. Thanks to him people realized that all the cinematographic language that had been enforced up to that point could be completely shattered. There was no need to show everything to your audience, no need for fade-in and fade-out or clear-cut transition. You could show a couple having dinner in one scene and in bed in the next; the audience is clever enough to bridge the transition for themselves.

Godard completely changed cinematographic grammar. After Breathless (1960) came out, all kinds of other filmmakers, such as René Clément with Plein Soleil (1960), embraced his elliptical editing technique.

|

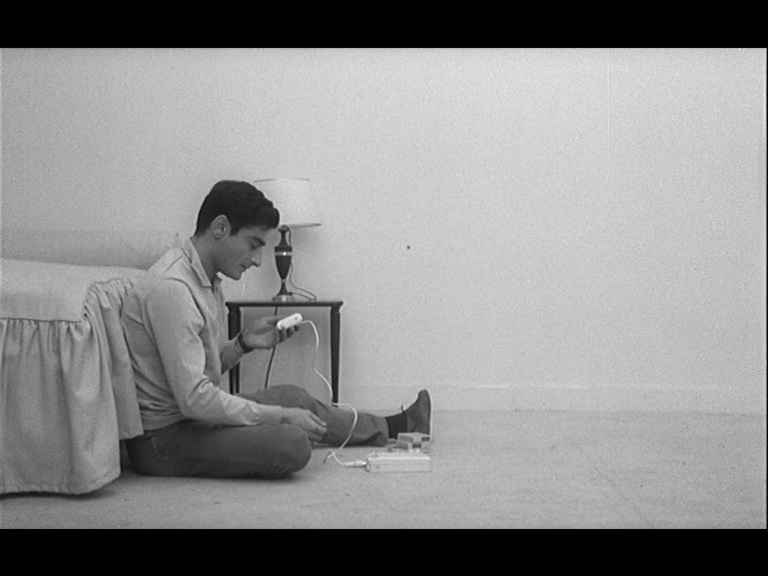

Charles Denner in La Vie à l’Envers, 1964 |

Your first feature film La Vie à l’Envers is still one of your best-known and most popular films. Can you describe the circumstances that led to the making of the film and what inspired you to write the screenplay?

I love suspense films so I wanted to make one. I optioned the rights of a novel by Robert Simon telling the story of man with multiple identities but that fell through. So my only option was to make an indoor suspense film, that’s how I wrote the screenplay of La Vie à l’Envers. The screenplay has now been turned into a book and the film is screened in medical schools in France and in psychiatric institutes in Chicago to illustrate schizophrenia.

The main character is an outwardly successful person who rejects his life and chooses instead to live a life of solitary contemplation, but everyone else thinks him mad. It seems deliberately ambiguous as to whether he is or not. Was that your intention?

Yes, right from the start. That’s what I find really fascinating with psychosis. The line between normal and abnormal is very fine indeed. When I started writing the film, I paid a visit to a psychiatrist friend who told me we all have the potential to become neurotic or psychotic. He recommended searching in myself to find inspiration for my character. With La Vie à l’Envers I was interested in showing the ambiguity between normal and abnormal.

You said in another interview: “The everyday bores me. For me a hero is someone who is different” – in La Vie à l’Envers the lead character is example of this. Is there something about characters most people would consider mad or delusional you identify with?

Absolutely, I identified with the protagonist. I do not mean to sound immodest but I think that’s the strength of great playwrights, filmmakers, and novelists. Flaubert used to say: “Madame Bovary it’s me”... that says it all.

What was it like to direct your first full-feature film? Was it what you expected it to be?

It’s one thing to learn technique but there comes at time when one has to face the demands and restrictions of the creative process. You realize you have to fight against the film technicians’ conformism. That’s something I felt really early on. At the time, films where in black and white, with very contrasting lights and lots of shadows, and I wanted to make a film in grey and white with almost no shadows. It took me a long time to find a head cameraman who would agree to shoot in grey and white – people thought I was mad. I think it’s the same with theatre companies, when you want to create an original production you have to fight against conformism.

|

Michel Duchaussoy in Jeu de Massacre (1967) |

Your next film, Jeu de Massacre, was stylistically quite different; it’s in colour and the pace is faster and more dynamic. Did you consciously change your method of directing for this film?

Jeu de Massacre was a completely different learning experience from La Vie a l’Envers. At first I wanted to make the film in black and white but the co-producer insisted it should be in colour. In the end this worked in the film’s favour, as I was inspired to recreate the look of comic books. Unfortunately there was not enough of a budget to transform the image exactly as I wanted it – I could not create blue grass and red sky, which is possible with digital technology today – but the trick was to work with filters to try and make scenes inspired by comics more colourful.

Like many of your films it has a memorable soundtrack – how did that come about?

The comic featured in the film, created by Guy Peellaert, was inspired by Pop Art so I needed a soundtrack to mirror Peellaert’s style. We found an English pop band (The Alan Brown Set) whose music matched the comic perfectly.

The film was quite a success, winning you the award for best screenplay at Cannes. You’ve written or co-written most the films you made. Why did you choose to make films from your own stories rather than adapt books?

Actually I now believe I should have tried to find inspiration in someone else’s work more. I’ve been a novelist for the past ten years and I feel I always have the same obsessions. I think finding inspiration in someone else’s work is essential to renew one’s style. There are also commercial reasons: it’s easier to pitch a film to a producer if it’s already been published as a book; it gives you something concrete to work with.

Your next project was La Planete Bleue, a science fiction screenplay you wrote that Carlo Ponti was interested in producing. Can you tell us about this project and why it never went into production?

After Jeu de Massacre I wanted to make my dream film so I wrote La Planete Bleue. I wanted to cast Julie Christie as the lead but the project was aborted. It was a really harsh experience for me. For a year or so I lived like a luxury tramp, producers took me to Rome, London and New York for endless meetings but the film never came about. There came a point when I’d had enough. I felt that even if the film had gone ahead, it would have been a bad one because I was already too emotional invested in it.

I also tried to secure financing for the film in Hollywood but It was a case of bad timing. The American film industry at that time was producing an increasing number of independent films with smaller budgets and La Planete Bleue would have been really expensive with lots of special effects. There are worse things in life, but this was probably the most distressing film experience I ever had.

Traitement de Choc was inspired by your own experiences of a health clinic wasn’t it?

|

Alain Delon and Anna Girardot in Traitement de Choc, 1973 |

Yes, after La Planete Bleue I was really exhausted so I spent a week in thalassotherapy. While I was there I had the idea of turning the experience into a horror film set in health clinic.

It’s quite a damning attack on the rich who exploit others to enhance their own standard of living. Do you think a film should have a moral point?

Whatever the film there is always a moral point, whether it’s made consciously or not. All of my films illustrate a moral except En Toute Innocence (1988), where I wanted to tell a simple story with good actors. But that was quite unusual for me.

I find it difficult to write a film without a moral stance. Traitement de Choc incorporates a lot of black humour, which is a great way to make your point, while also entertaining your audience.

The film starred two of France’s then biggest actors: Alain Delon and Annie Girardot. How was it working with them?

It was fantastic. They were both really professional and open-minded actors so everything went smoothly. Actors can’t stand it when they feel technique is more important to the film director than their own interpretation of their character. It’s really important to respect the artistry of an actor and to establish a good working relationship with them. That’s when miracles occur. That’s when actors will give you the best of their art – when they give it all. As a film director, you need to get to this point where you reach a complete understanding with the actor. This is something I experienced with Patrick Dewaere on Paradis Pour Tous (1982). It was a beautiful experience.

Your next film was Armaguedon (1977), which was an adaptation of the novel The Voice of Armegeddon by David Lippincott. What drew you to the story?

I read the book and I became fascinated by it and wanted to adapt it. I wanted to create a critique of voyeurism, of our society where life feels more and more like a reality TV show. Things have become very sensationalized and there no longer seems to be any difference between public life and private life. That’s what I denounce in the film.

Les Chiens (1979) shows how a breakdown of law and order inspires an even fiercer clampdown when residents of a suburb begin acquiring attack dogs to guard them. This looks even more relevant now than it was in the 1970s with ever increasing levels of violence and urban paranoia. What gave you the idea for the film?

I was recording the music for Armaguedon in Milan and I noticed that in the evenings there were dogs on leashes outside cafés. I was told the elderly took their dogs with them to protect them against potential muggers, so I simply pushed reality further.

|

Gerard Depardieu in Les Chiens (1979) |

How was the film received at the time?

No one believed in the film then; people thought it was unrealistic. Years later the violence showed in the film became reality. In France there were lots of accidents with people who had acquired attack dogs to protect them. It was a premonitory film if you like.

Despite the fascist overtones of his ideology I must admit if found Depardieu’s character, the dog trainer, quite sympathetic.

That’s great; that’s exactly what I set out to do. I want to make my audience empathize and somehow identify with my characters, whether they’re heroes or villains. Everyone is attracted to power to a certain extent and I think that’s why the audience is drawn to Depardieu’s character.

There are some gripping scenes of confrontation between people and dogs. Were they difficult to shoot?

Yes, shooting with dogs is challenging. The world of dog training is dangerous; dog owners tend to be rather deranged and they pass their aggressiveness on to their dogs. The canines are trained to bite, attack, hurt and aggressive behaviour is rewarded. It’s a strange world. The owner of the main dog in the film was a man in his thirties who had left his fiancée for the dog. The dog you see at the end of the film was a hybrid - half dog, half wolf – and its owner was covered in cuts. The dog was really unstable and dangerous.

|

Patrick Dewaere in Paradis pour tous, 1982 |

Paradis pour tous (1982) concerns a character played by Patrick Dewaere who is cured of depression by a new method called “flashage”, which seems like a miracle cure at first but leaves its recipients stuck in a permanent state of serene indifference. The film, released in 1982, seems extraordinarily prescient given the modern trend for medicalizing mental and emotional problems. It also targets consumer society and the world of business. What inspired you to write the script?

I was in California staying in a villa in Bel Air, casting actors for a film that never went into production. On a Saturday morning I went food shopping and at the till the cashier asked me how my day was and I said not so well. His reaction made me realize that by complaining I was breaking a social code. On the West Coast everyone is tanned, it’s sunny; on the surface everyone is happy. So I got the idea to create a film where everyone seems happy even if it’s a shallow and superficial form of happiness.

When Patrick Dewaere told me he wanted to be in the film I was delighted but I knew I would have to fight to see the film through to the end. His role is really difficult because his character is always happy but Dewaere had to show different nuances of happiness. His acting had to be extremely subtle but he nailed it. We got on really well and by the end of the shoot we did not even need to speak to each other; he would read my mind.

How did Frankestein 90 (1984) come about? Were you a fan of the earlier versions of the story?

I had to make a film because Paradis pour Tous was a really expensive and had also left me rather exhausted, so I needed a breath of fresh air. Frankenstein 90 is more of a producer’s film than a director’s film. It was an entertaining experience, working with actors I really liked, but it felt more like a break. I liked the earlier versions of the story and I really enjoy horror films, so it was a really pleasurable and refreshing experience. Unexpectedly, the film was a triumph in India.

|

Michel Serrault and Nathalie Baye in En Toute Innocence (1988) |

En Toute Innocence (1988), starring Nathalie Baye and Michel Serrault, is a comedy/thriller in the Hitchcockian style. Had you always wanted to make film of this type?

Yes, I wanted to show I could make a thriller but without an overarching moral. The film is indeed Hitchcockian, with the action set behind closed doors and this psychological war going on between a man and his stepdaughter. I thought Michel Serrault’s performance was outstanding and the story really appealed to the public.

When you were directing films did you like to improvise on set or did you prefer to storyboard every scene?

I really liked having a French-style script breakdown with scenes in the left side column and sound in the right side column and precise descriptions. Having said that, for really important scenes, I would always rehearse with actors and often the content would change. The storyboard was a reassuring aide-memoire to work from. If I were making films now I would have a completely different way of directing – with digital cameras I would improvise much more since one can shoot films more quickly.

Your last film, Les Couleurs du Diable (1997), is about a painter who makes a Faustian pact to become famous and successful. Can you tell us more about it?

The film was a rather bizarre and disappointing experience. I am not happy with it at all. I really liked the novel but these types of fantasy novels are really difficult to shoot in France. I was only able to shoot the film in Italy. I lacked funding and some special effects to make certain scenes really spectacular. The head cameraman, who had worked with Visconti, had really high expectations but my vision for the film was limited by our budget. Although I do have really fond memories of being on set and working with the Italian film technicians who are really passionate about what they do, I am really dissatisfied with the film itself.

Since the release of Les Couleurs du Diable in 1997, you have focused on writing novels. How does novel writing differ from scriptwriting for you?

When you write a script your style is very elliptical; there is no need to describe the mindset of characters as you know the actors will be able to convey their emotions. Novel writing is a much more in depth writing process. Film directors often adapt novels because the novelist gives them more material to work with than just an original screenplay. The novelist usually spends a couple of years perfecting a novel and that’s what’s missing with an original screenplay: it lacks depth.

How do you feel about the current state of film industry?

|

Armaguedon, 1977 |

Unquestionably there is an unprecedented pressure to make a film a commercial success and as a result a lot of interesting films are not even released in cinemas. It’s getting easier and easier materially speaking to make films and more and more difficult to distribute them. That’s exactly the problem encountered by French cinema at the moment: more than 300 French films are made every year and only 60 or so are shown in cinemas. It’s the same with literature: fewer publishers are willing to take risks and the majority prefers publishing books in a genre that has already proven commercially successful. It’s very paradoxical.

What would you say are some of the main themes and ideas you have tried to convey with your films and writing?

I am deeply interested in finding the uncanny in the ordinary: that little something unusual that occurs when reality is slightly shifted and seeing what would happen as a result. In that sense, some of my films are premonitory. I can’t make cinema that is too realistic. The poetic realism of pre-World War II French cinema expressed the mentality of the people at the time. It idealized French society and the way people perceived it. The dream was more telling about reality than a realistic film would have been. That’s what I’m interesting in. I like films that open up a different door onto reality and show a new world.

Interview by Simon Hitchman, © 2014, translation by Melissa Tricoire - please do not reprint or reuse without permission. |