|

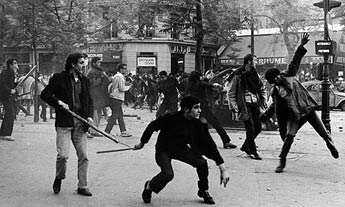

Paris Riots 1968 |

This piece was written as a response to a lecture by noted film scholar, author and previous editor of Les Cahiers du Cinema Antoine de Baecque at the "Nouvelle Vague: 50 Years On conference at The French Institute Cine Lumiere. March of 2009, London.

The world in the 1960s was a world on fire with change and revolution. It does seems strange, then, that when discussing the French New Wave the point of politics often receives only the lightest brushstrokes. Many are familiar with the Left Bank Group and their political leanings towards socialism and the radicalism of the left. Most fans of the Nouvelle Vague are aware of Godard's radicalisation later in his career. But what about Truffaut, Chabrol, or Godard before 1968? Were they really, as is sometimes murmured in academic circles, right-wing radicals and fascist sympathisers? How could they be fascists, when their films were so humane? What happened to Godard in the late 1960s? And if the Cahiers directors were so preoccupied with truthfully representing life, how could they do this without having some consciousness about the political world around them?

Content versus style

To begin with, it's probably helpful to get a rough idea of what it meant in 1950s France to be either "left-wing" or "right-wing". Every country, every time period, and every group has its own slightly unique take on the political spectrum. In the contemporary United States, for example, one might understand that to be "right-wing" is to uphold traditional and often religious social values, and to emphasise as little government interference as possible with either fiscal activities or people's every day lives. "Left-wing" thinking, on the other hand, might be said to emphasises fairness and equality for both majority and minority groups, progressive social values, and a government that is designed to interfere in order to keep greed and human failings in check.

For our purposes, however, we can understand that in post-war France, intellectuals tended to fall on one of two specific sides: "Left-wing" humanists, who believed that all art should have a social purpose or message, and "right-wing" freedomists, who believed that art should be able to exist for its own sake, or in fact only to express the truth.

In film, this boiled down to the question: which is more important? A socially progressive film? Or an aesthetically progressive one? Politics had drawn a line between the filmic camps of "content" and "style".

Chabrol and the "little theme"

|

Roland Barthes |

While The 400 Blows breakout success at Cannes in 1959 is often cited as the official start of the French New Wave, most consider the first film of the Nouvelle Vague to be Claude Chabrol's Le Beau Serge (1958), a film about a man, Francois, who returns home to his village after a long absence, only to find everyone still living in poverty and misery. Francois attempts to transform the lives of the villagers by organising them, and although he succeeds to some small degree, it is without much cooperation from the villagers themselves and most of the characters are left in the end to contend with their own stupidity. Leftists like Luis Bunuel and philosopher Roland Barthes immediately leapt on this film as right-wing propaganda - claiming that it imposed a static image of man and, specifically, a static and uncompassionate image of the poor. Roland Barthes wrote in his critique:

The peasants drink. Why? Because they’re very poor and have nothing to do. Why this misery, this abandon? Here the investigation stops or becomes sublimated: they are undoubtedly stupid in essence, it’s their nature. One certainly isn’t asking for a course in political economy on the causes of rural poverty. But an artist should acknowledge his responsibility for the terms he assigns to his explanations. [The political Right have] this fascination with immobility, which makes one describe outcomes without ever asking about, I won’t say causes... but functions.

|

Claude Chabrol |

But more than opposing the content of New Wave films, the Left opposed the anarchic style of the films, and they hated the way the Cahiers directors often seemed to prioritise style over substance, or rather to derive their substance from style itself. The Cahiers group were not exploring grand moral themes, they were exploring "little themes" and "micro-realities" and they were drawing few conclusions about what they found there. This, to the 1950s french bourgeois Left, was irresponsible and a reprehensible occupation for art.

But not everyone believed that art was indentured to social purpose. Chabrol responded to Barthes in the Cahiers du Cinema, by then already sporting a reputation as a "right-wing" film journal, by saying that "there is no such thing as a 'big theme' and a 'little theme', because the smaller the theme is, the more one can give it a big treatment. The truth is, truth is all that matters.” That, simply, was the crux of the argument between Left and Right. The Left wanted a utilitarian art of grand moral transformation, the Right only wanted to play with, examine, and expose reality as an exercise in truth.

While he didn't explore the conflict between Barthes and Chabrol specifically, in his recent lecture on the politics of the French New Wave, writer and film scholar Antoine de Baecque did make a list of properties that the members of the Cahiers group informally associated with the kind of film they wanted to make: properties which directly opposed the manifestos and ideologies of their left-wing contemporaries. These things are not, in themselves, a manifesto, but they do shed some light on what might have been going on in the minds of the Cahiers directors in those early years:

- a film's moral position should be in its form and style, not in an underlying social message in its narrative

- content is subject to style (aka "dandyism")

- short sentences and "micro-realisms" are preferrable to long discourses or discussions in film

- asking questions is more important than finding answers

- emphasise complexity

- emphasise confusion

- present what is real without trying to orient the audience

This was the stuff to short-circuit the tempers of the bourgeois Left! Underlying all of these ideas, said de Baecque, was less an antithetical ideology than a spirit of youthful, anti-bourgeois rebellion, a desire to shake things up and kick down the old guard in any way it could. It was not around Chabrol, however, that this spirit would eventually coalesce. It was Truffaut.

Truffaut, the fascist communist

|

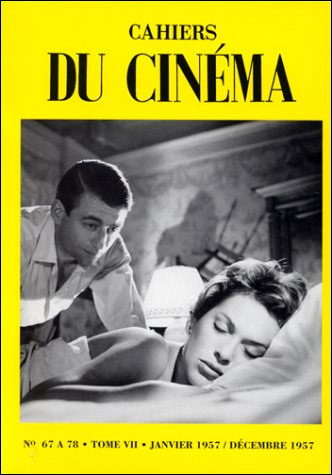

the Cahiers du Cinema |

While Godard, Malle, and many of the "Young Turks" were born into comfortable, middle class families, Truffaut's childhood reads very much like the plot of the (mostly autobiographical) 400 Blows: he was born to an unwed and impoverished mother who mostly ignored him; he endured regular beatings and scorn from his stepfather, was institutionalised in a home for "problem children" as an adolescent, later joined the army, deserted and was discharged dishonourably, and was then treated for venereal disease after contracting it from a variety of prostitutes. His early life was about as far a cry from Louis Malle's "silver spoon" upbringing as one could imagine.

He was also, while the youngest member of the Cahiers group of directors, the indisputable leader of the movement. In his early 20s, with almost no formal education, he was hailed as one of the greatest film critics of the twentieth century and his words were fuelled by a burning desire to shake up the status quo.

And shake it up he did. Over the course of his career as a critic, he wrote 528 articles for Arts-Lettres-Spectacles and 170 for Cahiers du Cinema, both considered bastions for the right-wing intelligentsia of the time. Many of these articles were brutal attacks on the French "cinema of quality", the type of high-minded, literary period films supported by the Left and held in esteem at festivals, often regarded as "untouchable" to criticism. These included films by directors such as Claude Autant-Lara, Jean Delannoy and Yves Allégret and screenwriters such as Jean Aurenche and Pierre Bost, and Truffaut hated every one.

His famous 1954 article “Une Certaine tendance du cinéma française” (“A Certain Tendancy of the French Cinema”) in Cahiers lambasted the "cinema of quality" and electrified many of his colleagues into action. Truffaut's restless and youthful spirit infected Godard and Rivette and others at Cahiers and, heeding his call, many were inspired to move beyond simply writing about film and to become directors. "The Nouvelle Vague was youth, it did not recreate it," said de Baecque in his lecture. " The New Wave were only able to capture the spirit of youth, of their time and of history, because they were against history." One thing was clear: with "Une Certaine tendance", the New Wave had formally declared war on what were currently perceived as France's greatest "artistic" films, the Left's "cinema of quality". And, once the gauntlet had been dropped, it was only a matter of time before the Left responded. Churning out pages of vitriolic criticism, they denounced the New Wave, and even accused Truffaut of being a fascist.

Truffaut, of course, adored the attention. He so loved stirring up the self-righteousness of the bourgeois Left that he even went out of his way to antagonise them. He defended censorship imposed on American films, praised a film text written by a Nazi collaborator and even paid tribute to the French monarchy. In short, he gave them every excuse to call him a fascist. But Truffaut's true political inclinations were somewhat more complex.

|

Directors on strike at the Cannes film festival, in solidarity with French students, May 1968.

(from left): Claude Lelouch, Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Roman Polanski and Louis Malle (standing). |

Truffaut's mentor and surrogate father figure after he left the army (and indeed the one who helped to get him out in the first place) was Andre Bazin. In the late 40s and 50s, Bazin was one of the most influential cinema critics in France and in 1951 went on to found the Cahiers du Cinema. Bazin was a leading intellectual and wrote a number of favorable essays about both western and eastern bloc works. He was also a Catholic, and refused to bend to the Leftist pressure which mounted after the war at many of the film magazines, a milieu which demanded that critics positively review Russian and European communist pictures for their moral messages, but negatively review American films for their capitalist bent, even if they were thought to have aesthetic value. Because Bazin praised films by Orson Welles and Howard Hawks for their form and stylistic innovation, both he and his theories were labelled "right-wing" by the Stalinist old guard. Although he himself would not identify with the label, it was Bazin's perceived "right-wing anarchist" values -- values of freedom and aesthetics in film -- that inevitably permeated Cahiers du Cinema and all of its writers -- especially its editor, Eric Rohmer and of course its most important critic and Bazin's protege, Truffaut.

These "right-wing" values, however, did not stop Truffaut in 1960 from signing the Manifesto of the 121, a document written by and signed by the leading left-wing intellectuals of the day, in opposition to the Algerian War. It nearly ruined his career and cost him several friends, but as a previous army deserter himself, Truffaut felt he must defend a soldier's right to object to fighting. In 1968, when the right-wing French culture minister André Malraux under Charles de Gaulle attempted to replace Henri Langlois as head of the Cinematheque Francais, Truffaut became involved in the Leftist student protests which culminated in the events now known as les evenements Mai 1968.

In Truffaut's biography, de Baeque writes:

As a public personality, Francois Truffaut was often asked to take a position regarding important issues in the political life of his country. But though he was passionately interested in politics and read the papers assiduously, he never ceased being wary of political commitment. In 1967, he turned down membership in the Legion of Honour from Minister of Cultural Affairs, Andre Malraux. "I gladly accept rewards for any of my films, but it is not the same where the duty of the citizen is concerned... it would be dishonest of me to solicit any national honour." What most bothered him about any poltical commitment was the simplification of reality, the Manichaeism implied in any militant discourse; for, as he put it, "life is neither Nazi, Communist, nor Gaullist, it is anarchistic."

In others words, if a left-wing cause moved him, Truffaut would take a stand. He refused, however, to let his art become shackled to any one ideology. This did not make him fascist or even apolitical. It made him... complex.

Complexity

"It is a paradox of the New Wave," said de Baecque, "that most modernity is born from the Left. The New Wave, however, because it was born of freedom, created modernity from the Right."

The politics of the New Wave is, undeniably, marked by complexity -- and this is not the only paradox. One of the most interesting things about the politics of the Cahiers group was that while through their antagonism of the Left they defined themselves as somewhat "right-wing", their actual beliefs and the beliefs espoused in the content of their films were a lot muddier, and certainly not ideologically "Right".

|

Anna Karina and Michel Subor in Godard's Le Petit Soldat |

De Baecque gave a couple of examples, namely Godard's Le Petit Soldat and Chabrol's Les Cousins, though there are many other films from this early time period that could be analysed in a similar way.

Godard's Le Petit Soldat, released in 1961 and banned in France for many years, is in some ways the epitome of right-wing anarchism. Created almost entirely on the fly, with Godard often coming up with action and dialogue the morning before shooting, there was little or no rehearsal for the actors. Le Petit Soldat is often called "chaotic" and "undisciplined" in style and some consider it an exercise in almost absolute freedom. And, confusingly, the story is at once both political and apolitical. The protagonist, a photojournalist and member of a pro-French anti-terrorist commando group, is ordered to kill a pacifist named Palivoda who is opposed to the Algerian War. Bruno has previously deserted the French army, professes to have no political ideals, and is suspected of being a double agent; thus, his colleagues assign him this particular task in order to test his loyalty. Palivoda encourages desertion from the Army and supports the Algerian Front de Liberation Nationale (FLN). Bruno, who would rather discuss art and the paintings of Paul Klee than fight or kill, meets and falls in love with a Leftist girl named Veronica (played by Anna Karina) who is also involved with the FLN. After Bruno is caught and tortured by the FLN (after failing to kill Palivoda), he escapes to Veronica's apartment. Later, he tries to explain how difficult it is to live as a man with none of his own ideals. He wonders whether he is "happy because he is free, or free because he is happy?". Planning to obtain escape visas from his commando group for himself and Veronica to escape to Brazil, Bruno decides at last to kill Palivoda. While he pursues and eventually kills Palivoda, however, his "friends" in the commando group discover Veronica's ties to the FLN and kidnap, torture, and murder her. At the end, Bruno explains that he has learned not to be bitter about the horrible things that have befallen him, and that at least he is young and has more time to live and find happiness.

The Algerian war was ongoing when Le Petit Soldat was released, and the French government was not happy with the way its army was portrayed, especially the film's exposure of both the army's and the FLN's use of torture on its captors. Censors who banned the film explained, "At a time when young Frenchman are being called upon to fight and serve in Algeria, it seems quite impossible to allow this oppositional conduct to be exposed, presented, and finally justified. The fact that [the protagonist] is paradoxically engaged in a counterterrorist action does not change the fundamental problem."

"Paradoxical", again, was exactly right: De Baecque described Bruno as a romantic character who "thinks on the left in a right-wing situation". Bruno has no interest in killing anyone. He himself is a deserter more interested in art and love than fighting. He is, however, only "half on the Left" because he lacks any personal ideals, and because he seems more interested in his own freedom and happiness than any kind of greater social good. Veronica's character is left-wing and sympathetic, and her death at the hands of Bruno's fellow soldiers is portrayed as a great injustice. The ending, however, is unexpected and confusing. We might expect that Bruno will vow to seek revenge for Veronica's death, or that he will join the FLN himself, or even that he will vow to eradicate the FLN on behalf of the French army -- really, any action which might portray him to have taken on an ideology of his own. Instead, Bruno decides to do nothing and escapes from the experience still free from ideals and happy, in fact, to be young and free.

|

1962 newspaper reporting on left-wing demonstrations against the Algerian War. |

This may not have been an attempt on Godard's part to justify Bruno's behaviour. De Baecque points out that Godard has always been fascinated with the losers of history - or rather, those who have been made wrong by history. But instead of trying to explain or justify a particular political point of view, he was really just interested in exploring the complexity of human nature. People are sometimes static, sometimes indecisive, sometime unheroic, sometimes all of those things and also their opposites. Le Petit Soldat is confusing, because people are confusing. Sometimes, neither Left nor Right have got it completely correct, and sometimes destruction results from both ideologies and non-ideologies alike. The world is a complex place, and Godard was concerned with exploring that complexity, without trying to engineer a filmic reality to fit a particular conception of it.

Many of the other Cahiers directors were of a similar mind, whether or not they signed the Manifesto of the 121. "Left" and "Right", to them, were "labels that politicians used to conveniently parse up reality," explained de Baeque. These labels were used to simplify conflicts, to stir up support, and to divide people without enlightening them, so that they could be controlled. "What politicians say does not necessarily encompass what is true," said de Baecque. Thus the New Wave viewed the 'political spectrum' as too simplistic to be an accurate reflection of the more multi-dimensional map of real orientations and beliefs. It would be wrong to call their films apolitical. It would probably be more correct to say that just as the New Wave were stylistically and narratively inventive, they were politically inventive as well.

But where did all of this inventiveness come from? And why did it happen when it did? What did the New Wave have to do with the 1960s?

The "Spirit of Youth"

"The Nouvelle Vague was youth, it did not recreate it. The New Wave was able to capture the spirit of youth, of their time and of history, because they were against history."

|

Maurice Ronet in Malle's Le Feu Follet |

Youth was a recurring theme of the lecture, and De Baecque was particularly interested in what it was about the 1960s that had proved such fertile soil for creativity of the young Cahiers directors. He talked a bit about the character of Alain Leroy in Louis Malle's Le Feu Follet, who laments he has "had it with mediocrity!" Like the Cahiers directors, Leroy is trapped in a bourgeois existence and his despair, said de Baecque, stems from a vague feeling that there is nowhere left, in post-war France, to prove himself and what he is made of. De Baecque argued that Godard, Truffaut, and the other directors of the New Wave who grew up in the shadow of World War II, realized that when they came of age, there were no real revolutions left to fight. On the one hand, they were living in peaceable times: the war had been won and technology had made life easy and convenient. Peace meant that most of their heroes were fictional and detached from the real world, and most young people were content to live in fantasy. On the other hand, the idea of Hiroshima seemed at once to make the future uncertain and any old ideas about war obsolete; wars need no longer be fought, but total destruction was still possible and perhaps even imminent. De Baecque contended that the idea of a possible nuclear war, both as preventative to any personal involvement in a classical revolution and as a threat to the stability of a longterm future, created a kind of anarchic punk mentality in the minds of the Cahiers generation, facilitating the idea that there might be "nothing to be expected from the future."

De Baecque quoted Alain Resnais, who said: "Hiroshima taught me that the world was neither serious nor lasting. I turned 20 at the end of civilisation." That is to say, what is there to conquer in the wake of the possibility of nuclear holocaust? Rather than driving the directors of the Nouvelle Vague to nihilism, however, de Baecque thought that it drove them to take on intellectual and artistic revolution as a way of embracing the freedom and life of the "now".

The French New Wave, then, was a seed from which the rebellious youth culture of the 1960s grew, not because it invented it, but because it articulated what was already there. De Baecque noted that because the New Wave were youth and spontaneity and rebellion, and because their style was, formally, a politics of revolution, one could say that while none of them filmed the event, they were, aesthetically, with the protests of May 1968 in spirit. The youth of the 1960s found themselves more or less "in synch" with what the Nouvelle Vague was creating, and because each identified with each other, the two were able to create a new form of French mythology.

"Chabrol's decadence, Resnais's guilt, Truffaut's nostalgia, Godard's rebelliousness - these were all things that appeared 'out of synch' with what was, at the time, considered modern," said de Baecque. Namely, modern Leftist sentiment. "However," he continued, "by daring to by 'out of synch', they in fact created a new way of being 'right on time'."

Godard, and shifting to the left

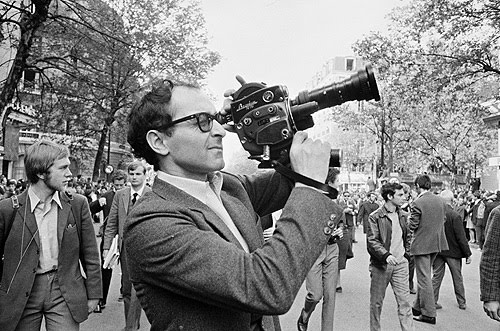

|

Godard takes to the streets. |

One of the luxuries of being unfettered by a specific ideology is retaining the freedom to change one's mind, or rather the freedom to let one's mind evolve over time.

By the mid 1960s, it became difficult for the writers of the Cahiers du Cinema to ignore that the world around them was radically changing. The still staunchly Bazinite Eric Rohmer was ousted as editor of the magazine in 1963 and Jacques Rivette took the helm. In order to broaden the scope of Cahiers, Rivette shifted its focus and the writing began to take into account developments in European cinema, moving away from aesthetically based Bazinian criticism towards a more politically centered Brechtian model. After Rivette left in 1965, and after losing a large portion of its readership, Cahiers finally settled in the 1970s into what is still referred to as the magazine's "Mao decade", a decade marked by its commitment to liberal Leftist politics. The magazine's previous, and rather precarious, commercial position as "aesthetically right-wing" or "right-wing anarchic", which fit neither the attitude of de Gaulle's Right or that of the bourgeois Left of the 1950s, had become impossible to reconcile in a changing world which was being increasingly defined as being at "social war". Bazin's attitudes suddenly seemed less revolutionary or important than Vietnam or May 1968, and so Cahiers was, at least for a time, absorbed into the Left.

|

Anne Wiazemsky in Godard's La Chinoise |

Meanwhile, while many of the first Cahiers critics, now well-established directors, remained politically ambiguous, Godard was undergoing a political change of heart. With his youth behind him and his career secure, Godard no longer needed to shock or provoke and it became increasingly hard for him to ignore that in contemporary France, to be right-wing meant more than just prioritising aesthetics over content. Why it became hard for him to ignore this was both a personal and an intellectual revelation. He was mobilised, in part, by the atrocities of the Vietnam War and the increasingly repressive policies of de Gaulle's government. He had also split with Anna Karina, and -- much like his hero in Le Petit Soldat -- Godard fell in love with a Leftist girl, soon afterward befriending a young Maoist literary critic for Le Monde named Jean-Pierre Gorin. The Leftist girl, Anne Wiazemsky, was a student and the star of one of Godard's favourite films, Bresson's Au Hasard Balthazar. Like Karina, for a period Wiazemsky was his muse, starring in La Chinoise and appearing in both Week End and Sympathy for the Devil. She was also a Maoist, and through his love for her, and the influence of Gorin and the political energies of the time, Godard became radicalised. In fact, many believe that La Chinoise, a 1967 film about a student Maoist cell whose members discuss and commit acts of terrorism, was a key influence on the 1968 student rioters. La Chinoise was the beginning of Godard's Dziga Vertov period, so named after the Maoist Dziga Vertov Group he formed with Gorin and several others. He has, however, continued to make political films throughout his career -- although they became more about individual freedoms and less about social upheaval after his split with Wiazemsky and once he began his relationship with Anne-Marie Miéville, who inspired him to take his creativity in other directions.

Godard's evolution through the so-called political spectrum exemplifies how the New Wave transcended political labels in exchange for a more realistic and human take on politics. All of the directors of the Nouvelle Vague were interested in people, and the truth of how individuals could honestly react in both ordinary and troubling situations. The radical climate of the 1960s often brought the best and worst of human nature into sharp relief, and the New Wave evolved as the reality of the world evolved. Godard once said, “At the cinema, we do not think, we are thought." Rather than working to progress a particular agenda, the New Wave helped to hold up a mirror to the complex, conflicting political and critical ideas that grew out of a period of great change. And just as any mirror can be angled to start a fire, the New Wave used art to inspire and catalyse 20th century cultural revolution. |