<< continued from page one

Auteur Theory

Alfred Hitchcock

...

|

For the New Wave critics, the “concept of the auteur” was the key theoretical idea underlying their aesthetic viewpoint. Although Andre Bazin and others had been arguing for some time that a film should reflect the director’s personal vision, it was Truffaut who first coined the phrase “la politique des auteurs” in his article "Une certaine tendance du cinéma français". He maintained that the best directors have a distinctive style, as well as consistent themes running through their films, and it was this individual creative vision that made the director the true author of the film.

Howard Hawks

|

At the time auteur theory was considered a radical new approach to cinema. Before, it had been the screenwriter, or the producer, or the Hollywood studio, who was seen as the principle creator of a picture. The Cahiers critics applied the theory to directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks who had previously been seen as merely excellent craftsmen, but had never been taken seriously as artists. By uncovering the complex depths in the work of directors like these, the young writers broke new ground, not only in the way a film was understood, but in how cinema itself was perceived.

Mainly as a result of this radical new way of looking at cinema, the reputation of Cahiers du Cinéma began to grow. In Hollywood the review became essential reading and directors like Fritz Lang, Joseph Mankiewicz and Nicholas Ray were photographed with a copy of the magazine in their hands. Filmmakers like these weren’t used to people discussing their work with such accuracy and depth. They were deeply impressed by these young enthusiasts with their strong opinions and perceptive insights into the art of cinema.

Inevitably, as the ideas and writing of the Cahiers critics became better known, there was a backlash. The aggressiveness of the review was felt to be too extreme by some. It brought about a feeling of resentment, and even hatred, in those targetted. As a result a kind of warfare raged between the young radicals and the old guard of French cinema.

The young group of writers at Cahiers du Cinéma were not content however, with merely being critics. They wanted to be filmmakers too. At the time there were two recognised routes to becoming a director. You could go through a long apprenticeship as an assistant director until, after many years, you were finally deemed ready to call the shots yourself. This approach was antithetical to the desires of impatient young directors with ideas of their own and a disdain for the conservative material they would have to work on.

Les Sang des Betes [1949]

...

|

The other method was to apply for a short film funding scheme. This government approved scheme ensured all films were made to a professional standard and was equivalent to a number of assistant positions. In the end, it enabled the candidate to obtain the work card needed to make features. Some of the older members of the New Wave began this way by making critically acclaimed documentaries: Georges Franju (Les Sang des bêtes, Hôtel des Invalides), Alain Resnais (Night and Fog, Toute Le Mémoire du Monde, Le Chant du Styrene), and Chris Marker (Les Satues Meurent Aussi, Dimanche a Pekin, Lettre de Siberie), and Pierre Kast (Les Femmes du Louvre). Others soon followed their example including Louis Malle (Le Monde du Silence), Agnes Varda (La Pointe-Courte), and Jacques Demy (Le Sabotier du Val de Loire).

The Cahiers group, however, rejected both of these approaches. They knew they would have to bypass the rules of the system if they wanted to break into the industry and make the kind of films they wanted to make. While still writing for the magazine, they gained experience and contacts. Chabrol worked as a publicist at 20th Century-Fox, Godard worked as a press agent, Truffaut worked as an assistant for Max Ophuls and Roberto Rossellini, and Rivette worked with Jean Renoir and Jacques Becker.

Les Mistons [1957]

...

|

Sooner or later, though, they realised, if they wanted to direct, they would have to start by making short films, raising money anyway they could. Rohmer began in 1950, directing Journal d’un Scélérat, followed by Charlotte et Son Steak. Rivette, working with a script by Chabrol, directed Coup du Berger. In 1952 Godard directed a documentary called Operation Beton about the building of the Grande Dixene dam in Switzerland. He made the film with funds he earned by working as a labourer on the dam. After selling this, he had the means to make two dramatic shorts: Une Femme Coquette and Tous Les Garcons S’Appellent Patrick. As they gained experience, their films became more sophisticated. Rohmer made Bérénice in 1954, La Sonate a Kreuzer in 1956, and Véronique et son Cancre in 1958, to increasingly high standards.

Meanwhile, Truffaut had set up his own film company, Les Films du Carrosse, with the help of his wealthy new father in law, and in the summer of 1957, shot Les Mistons, based on a story by Maurice Pons. Pleased with the success of the film, its financial backer suggested he make another. Truffaut began making a short comedy set against the backdrop of the flooding that had been taking place in and around Paris at the time, but had trouble finding the right tone and handed over the footage he’d shot to Godard. Godard felt no obligation to follow Truffaut’s script however, and created an unconnected story with an off the wall commentary that broke all the conventions followed by traditional filmmaking. This film, Une Histoire d’Eau, was the most original, and most New Wave, of all the short films produced at the time.

Other important shorts made at this time, and in subsequent years, included Le Bel Indifferent (1957) by Jacques Demy, Pourvu Qu’On Ait L’Ivresse (1958) by Jean-Daniel Pollet, and Blue Jeans (1958) by Jacques Rozier. These were followed by by first films from Maurice Pialet (Janine, 1961), Jean-Marie Straub (Machorka-Muff, 1963), and Jean Eustache (Du Cote de Robinson, 1964).

When the New Wave directors graduated from making short films to feature films in the late 1950’s, their ability to do so came about largely as the result of a combination of fortunate coincidences. Up until this time, filmmaking had always been an expensive business and it was necessary to have the backing of a major studio. Now, new circumstances came into play that enabled them to bypass this stumbling block.

After the war, the Gaullist government had brought in subsidies to support homegrown culture. A further act, 1958’s "Constitution of the Fifth Republic", resulted in more money being available for first time filmmakers than ever before. Private investment money became more readily available and distributors were keen to back new directors.

At the same time, technological developments meant filmmaking equipment was becoming cheaper. New, lightweight, hand-held cameras, developed for use in documentaries, such as the Eclair and Arriflex were now available, as were faster film stocks which required less light, and portable sound and lighting equipment. These advancements meant filmmakers no longer needed a studio to make a film. They could now go out and shoot on location using smaller crews set against authentic backdrops. Working fast on low budgets encouraged experimentation and improvisation and gave the directors more control over their work than they might have had otherwise.

Et Dieu... Crea La Femme

(And God Created Woman) [1956]

....

|

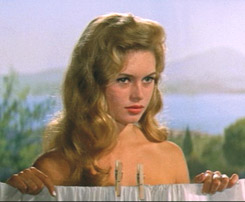

Et Dieu... Crea La Femme (And God Created Woman) (1956) is often cited as the first New Wave feature film. Directed by a 28 year old writer-director named Roger Vadim, and starring his then wife, 22 year old former model and dancer, Brigitte Bardot, it celebrated beauty and youthful rebellion and proved that a low budget film made by a first time director could be a success both at home and abroad. Although now somewhat dated, at the time the film was an inspiration to young directors hoping to make their first film on their own terms.

An even more inspiring figure was Jean-Pierre Melville, whose 1956 crime caper Bob Le Flambeur (Bob The Gambler) was a landmark in the French thriller genre. Shot on location on the streets of Paris and in the director’s own home made studio, its portrayal of the doomed gambler of the title, was both grittily realistic and audaciously stylized. The New Wave critics quickly recognised that Melville was the real deal: a maverick with an authentic cinematic vision all his own.

Worlds away from Melville's tough gangsters were the strange, haunting films of Georges Franju. Co-founder of the Cinématheque Francais, Franju had graduated from archivist to film-maker with shorts like Le Sang des Bêtes shot in a Parisian slaughter house. His ability to combine the poetic and the graphic, and to evoke the uncanny in a realistic setting, were seen to full effect in La Tête Contre Les Murs (Head Against the Wall) (1958), and Les Yeux Sans Visage (Eyes Without a Face) (1959).

Le Beau Serge [1958]

|

Louis Malle made his name working with marine scientist Jacques Cousteau on the Palme d’Or-winning underwater documentary Le Monde Du Silence (The Silent World) . Coming from a wealthy background, Malle was able to raise the money to make his feature film debut Ascenseur Pour L’Echafaud (Elevator to the Gallows) in 1957 when he was still only 25 years old. Featuring a breakthrough performance from Jeanne Moreau in the lead and Miles Davis groundbreaking soundtrack, the picture – a fatalistic film noir – was a success. He followed this up with Les Amants (The Lovers) in 1958, again starring Moreau. The film provoked considerable controversy over its frank treatment of sexuality, and partly as a result of this, became an even bigger success, marking out the young director as a rising talent.

Claude Chabrol was the first of the Cahiers critics to make the move into feature films. Using money inherited from his wife’s family, Chabrol wrote, directed and produced Le Beau Serge (Beautiful Serge) (1958), featuring Jean-Claude Brialy and Gerard Blain in the lead roles, despite having no previous filmmaking experience. Shot on location in a provincial village, using natural light, the film upset the professional establishment by breaking the rules of what they considered good film-making, and it was refused entry to Cannes. However, the director took it to the festival himself where it was well received, earning enough in sales to finance his next feature, Les Cousins (The Cousins) (1959).

Set in Paris, Les Cousins again starred Brialy and Blain, in a plot that effectively reversed the scenario of Le Beau Serge. The film was both a critical (it won the Golden Bear at the 1959 Berlin Film Festival) and commercial success. Having broken through as a director, Chabrol used the production company he had set up to support the debut films of Jacques Rivette (Paris Nous Appartient) and Eric Rohmer (Le Signe du Lion).

Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows) [1959]

|

The term New Wave first appeared in 1957 in an article in L’Express entitled “Report on Today’s Youth.” The article, by the journalist Francoise Giroud, and the book she published the following year called The New Wave: Portrait of Today’s Youth, had nothing to do with cinema, but was about the need for change in society. However, the term was borrowed by journalists who used it to apply to the young directors creating a storm at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival, and soon the phrase caught on internationally.

The film most responsible for bringing the attention of the world to this new cinematic movement was Francois Truffaut’s Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows) (1959). It caused a sensation at the festival that year. Its young star, Jean-Pierre Leaud,was carried out of the screening in triumph and Truffaut won the best director award. Suddenly the world’s media were talking about the New Wave. Ironically, Truffaut had been banned from the festival the previous year because of his uncomplimentary remarks about French cinema in Cahiers. Now he was a star director and those who had opposed him were rapidly pushed aside.

Also screened at Cannes that year was Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima, Mon Amour, which was awarded the International Critics’ Prize. Resnais had already made a name for himself as a documentary director with Nuit Et Brouillard (Night and Fog) (1955), the first film to focus on the Nazi concentration camps of the Second World War. Like the documentary, his debut feature film used innovative use of flashback, to illuminate themes of time and memory and the horror of war. The film was acclaimed for its originality and became an international hit.

continues on page 3 >>

|