Since they first appeared on screens over fifty years ago, the films of the Nouvelle Vague have never gone out of fashion. Over the years, generations of moviegoers have discovered and appropriated the looks and attitudes of the movement. Here we take a spin through the three key trends that defined a generation of masculine style...

French Gangster Style:

|

Lino Ventura and Jean Gabin in Touchez pas au Grisbi (1954) |

As tough as Cagney, as quixotic as Bogart, as cool as MacQueen, as steely as Marvin – through the years the French tough guy has proved himself a worthy match for his Hollywood counterparts. From Jean Gabin in Pépé le Moko (1937) to Lino Ventura in Classe tous risques (1960), Jean-Paul Belmondo in Breathless (1960) to Alain Delon in Le Samourai (1967), French cinema has had its share of hardboiled gangsters and existential loners who live by their own rules and to hell with the consequences.

Elements of French Gangster Style

Clothes:

Hair:

- slick or sleeked back with Brylcreem

, a la Delon, Gabin, or Ventura , a la Delon, Gabin, or Ventura

- alternatively, artfully mussed a la Belmondo

Cologne:

Attitude:

- uncompromising, steely, resolute

|

|

|

For the French movie tough guy, his style is a reflection of his natural dominance and flair for creative risk-taking. French cinema of the 1950s is rife with examples. One look at Jacques Becker’s Touchez pas au Grisbi (1954), for example, and one can't help but be impressed by the immaculately cut Camps de Luca suits worn by battling rival gangsters Gabin and Ventura. Or think of Yves Montand in Le Salaire de la peur (The Wages of Fear, 1953), transporting explosive nitro-glycerine through the steamy South American jungle wearing a stylish white vest and jaunty neckerchief. These are men who would cut a dash no matter how perilous the circumstances.

And it's not just his appearance that concerns the French tough guy. While the hardboiled American gangster is quick to impress that he is too tough to care about the traditional pleasures of home and hearth, by contrast creature comforts are essential to the existence of the Gallic gunman. There is an unforgettable scene in Touchez pas au Grisbi when Gabin’s character and an accomplice, on the run from both the police and underworld rivals, retreat to a hideout for the night. Here Gabin first proceeds to rustle up an appetising dinner of pâté on continental toast with accompanying bottle of wine. Then, when it’s time for bed, he produces an immaculate pair of pyjamas, towel and toothbrush for both himself and his friend! His friend doesn’t find it at all surprising to be treated with such hospitality; the French gangster never stints on these things.

It is more than his concern with the finer things in life, however, that sets the French tough guy apart. There’s also his absorption in the deeper philosophical questions of life. Unsurprisingly, as these characters spring from the country that brought us existentialism, ennui is never far below the surface. In Bob le flambeur, when Bob (Roger Duchesne) looks at himself in the mirror and comments, “A real hood’s face!” he is not making a joke. This is a statement of great melancholy, and one by which he takes stock of his entire life. But this sense of world-weary fatalism, rather than softening his edge, only adds to the Gallic tough guy’s charismatic appeal.

|

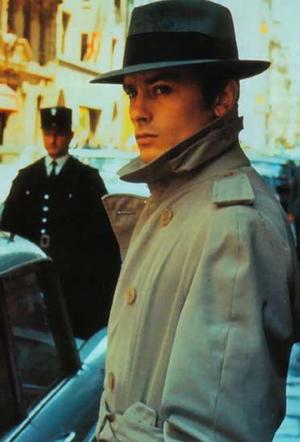

Alain Delon in Le Samourai (1967) |

The French screen gangster as style icon reached his apotheosis in the work of Jean-Pierre Melville. Taking his cue from Hollywood crime and noir movies of the 1930s and 40s, Melville’s criminal protagonists become idealised figures – knights of the underworld in belted trenchcoats and fedora hats, armed with handguns instead of swords. The director, ever attentive to every detail of his productions, designed their wardrobes himself. Tough and taciturn, these “ice-cold angels”, as the director himself described them, lived by a code of honour, of loyalty, and of courage. As embodied by Jean-Paul Belmondo, Alain Delon and others, the Melvillian loner set a new standard in cinematic cool that contemporary directors like Quentin Tarantino and John Woo, have sought to emulate ever since.

|

Jean-Paul Belmondo in Breathless (1960) |

Meanwhile, at Cahiers du Cinéma, the young band of critics weekly firing salvoes at the tameness of much of contemporary French cinema were equally passionate about Hollywood crime and noir movies. Naturally, therefore, when they came to direct their own films, some of them chose the genre as a vehicle through which to tell their own stories.

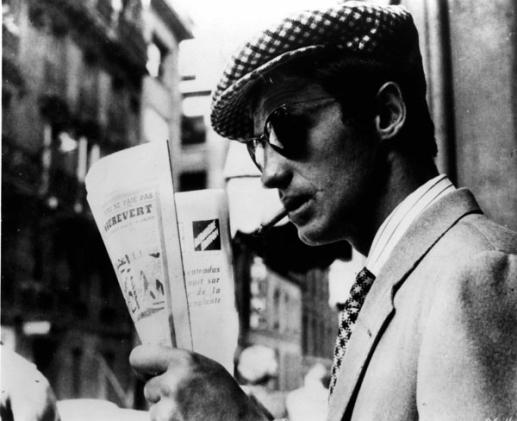

Chief amongst these was Jean-Luc Godard, who, with his black suit and tie and perennial dark glasses, looked like he might have stepped out of a B movie underworld setting himself. Not content to rework the established conventions of the genre, Godard, with his debut À Bout de soufflé (Breathless, 1960), took the basic elements – characters, props, plot-twists – and turned them on their head, creating something completely new in the process. The film made a star out of Jean-Paul Belmondo , whose unique take on the tough-guy style and persona resulted in a wave of “Belmondism” in the hipper circles of Paris.

Elements of French New Wave Dandy Style

Clothes:

Hair:

- neat and perfectly coiffed

Cologne:

Attitude:

- witty, sophisticated, cynical, urbane, laid-back, fatalistic

|

|

|

|

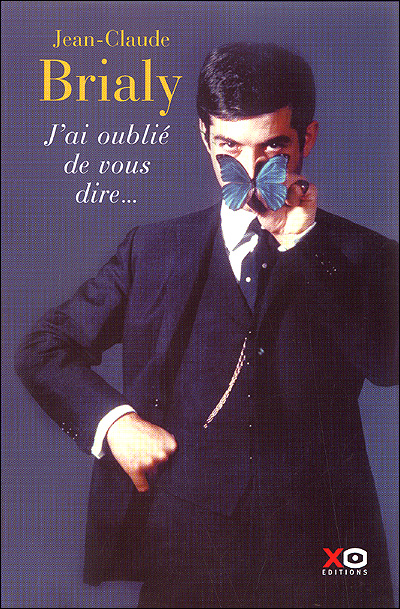

Jean-Claude Brialy |

The emergence of the Nouvelle Vague in the late 1950s heralded the arrival of a clutch of dazzling new female stars, whose cool sexiness and modern way of communicating and behaving became synonymous with this audacious new cinematic movement, helping to popularize it around the world. At the same time, an equally stylish group of young actors matched them in looks and attitude.

Hip, smart and sophisticated, these ‘dandies’ had a well-dressed, urban style and an intuitive, sometimes irreverent approach to acting that embodied the ideological and cinematic goals of the New Wave directors.

One of the most distinctive examples of the new breed was Jean-Claude Brialy. Relaxed, seductive and charming, Brialy, in films like Jean-Luc Godard’s early short Charlotte et Véronique ou Tous les garcons s’appellent Patrick (Charlotte and Véronique, or: All Boys Are Called Patrick, 1957); Claude Chabrol’s Les Cousins (1958) and Les Godelureaux (Wise Guys, 1961); and Pierre Kast’s Le Bel âge (1960), epitomized the suave seducer, the debonair playboy, the urbane socialite with a dark streak.

|

Maurice Ronet |

On-screen, Brialy always appeared effortlessly stylish, whether sporting an elegant suit and tie; polo neck, blazer and scarf; or, in Eric Rohmer’s later film Le Genou de Claire (Claire’s Knee, 1970), open necked shirt and bohemian straw hat. Off-screen, he was known as a brilliant raconteur, as an accomplished stage performer, and as a restaurant-owning, bon viveur.

|

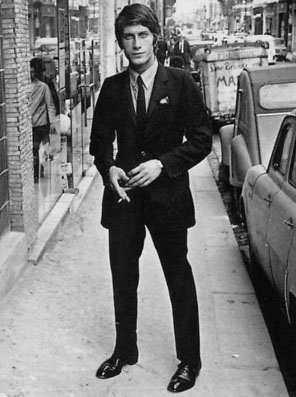

Jacques Dutronc |

Maurice Ronet, whose screen persona fell somewhere between a French James Bond and a doomed character from an F. Scott Fitzgerald story, was a variation of the type. He specialized in playing romantic loners with a fatalistic outlook. In his greatest role, Louis Malle’s Le Feu follet (1963), he played a world-weary alcoholic who has decided to commit suicide but visits his friends in Paris one last time in an attempt at finding a reason to continue living.

With his wry smile, elegant apparel and soft-spoken charm, Ronet had the kind of charisma that most men only dream about, and yet, impressing others had little value for him. He represented the dandy in hell: a wounded soul, disillusioned with a world that had failed to live up to his expectations. Like the character he played in Le Feu follet, Ronet was an alcholic who died young at the age of 55.

A generation younger, Jacques Dutronc first found fame as a pop/rock singer, scoring a string of hits in the late 1960s, notable for their catchy melodies and witty, pointed lyrics. Often pictured in a chic Renoma suit, Dutronc had Parisian mod attitude to spare. Later he would work as an actor for Jean-Luc Godard, Barbet Schroeder and Maurice Pialat.

The Truffaut-esque Hero:

Elements of Antoine Doinel Style

Clothes:

- lumberjack jacket

, battered brown leather jacket, or pea coat , battered brown leather jacket, or pea coat

- slightly scruffy V-neck vintage sweaters in bright colours or black

- brightly coloured scarves or ties

- tweed jacket

- battered fedora

or trilby or trilby - or no hat at all. - or no hat at all.

Hair:

- perpetually rumpled, or long and floppy

Cologne:

Attitude:

- poetic, rebellious, quirky, imaginative, romantic, boyish, troubled, charming

|

|

|

|

Jean-Pierre Leaud in Les Quatre cents coups (1959) |

Like any true auteur Francois Truffaut never failed to put his own personal stamp on his movies. The heroes of his films, in particular, reflected many of his own personality traits, none more so than the autobiographical figure of Antoine Doinel who first appeared in Les Quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows, 1959). Like those other great fictional teen rebels of the 1950s – Holden Caulfield and Jim Stark – Doinel is a bundle of contradictions: sensitive yet anti-authoritarian, intelligent yet inarticulate, daring yet indecisive. He longs for adult approval but cannot stop getting into trouble.

A large part of Antoine Doinel’s appeal lay in the looks, manner and style of the actor who played him. Onscreen Jean-Pierre Léaud managed to project defiance and vulnerability in equal measure. His deadpan solemnity, reminiscent of a silent movie comedian, and his instinctive, in the moment commitment to whatever situation the character was in, made him seem authentic – sometimes funny, sometimes frustrating, always real. In Les Quatre cents coups, his distinctive look – spiky hair, lumberjack coat and polo neck sweater – marked him out as both an outsider and a fashion influence. Punk pioneer Richard Hell was so inspired by the young Doinel he based his “blank generation” look on him; a look, which in turn influenced other musicians and legions of disaffected youth.

|

Jean-Pierre Leaud thoughtfully prepares a cup of tea. |

In the later films Antoine smartens up but retains a consistent air of dishevelment in keeping with the turbulent emotions smouldering beneath the surface. While on the surface his appearance conforms perfectly with our idea of a stylish young Parisian of the time, there is, at the same time, something old fashioned in his dress and way of acting. This is no accident. As Truffaut himself explained in his forward to the published Doinel scripts:

“It is precisely because of his anachronism and romanticism that I found Jean-Pierre so appealing. He is a young man of the nineteenth century. As for myself, I am a nostalgic. I am not tuned in on what is modern, it is in the past that I find my inspiration”.

No wonder then that he returned again and again in his films to period settings or that, even in his contemporary films, his leading protagonists seem to have stepped out of an earlier more sincere and romantic era.

|