|

Geoff Andrew, BFI Head of Film Programme |

In anticipation of BFI Southbank’s major retrospective of the work of Martin Scorsese, newwavefilm.com interviews the season’s curator and Programmer-at-large at the BFI, Geoff Andrew, about the qualities that make Scorsese one of the greatest and most influential American directors of his generation.

As the curator of this two-month Scorsese retrospective here at the BFI, can you give a brief overview of what the season will include and recommend some highlights for our readers?

It will include most but not absolutely everything that he has done. We've worked together with his team and there were some things that they were not so keen for us to show – certain short films and some of the television stuff – but it's pretty complete. We're certainly showing all the features and the major documentaries, and we're reviving two or three of them as extended runs. So we're doing Taxi Driver and Goodfellas, and we're also showing Silence, the new film, which is fascinating, so it's good that we're able to screen that at the time of the retrospective. We also thought it would be quite nice to celebrate his work in preservation and conservation through the World Film Foundation, so we invited him to choose a selection of films that they have helped to restore. There's a real mixture, some of it is international, quite a lot of it is American, but there's some real rarities in there too.

Scorsese often talks about the extraordinary impact movies had on him when he was growing up. Like Francois Truffaut he seems to have been completely immersed in cinema from a young age and he has an encyclopedic knowledge of the medium.

Yes, if memory serves, I think he suffered from asthma as a child and had to take a fair amount of time at home, where, apart from reading, he also liked watching films on television. And because he came from an Italian-American family, he wasn't just watching Westerns; they were also, in those days, watching neorealist films from Italy. So he seems to have got the film bug very early on in life, and it's never left him. He still seems to keep very much abreast of what's happening. I know that because I've spoken to various filmmakers and they said that when they met Scorsese he seemed to know their films. So he obviously tries to watch a lot, even now.

And his upbringing in Little Italy in New York was another formative influence wasn’t it?

|

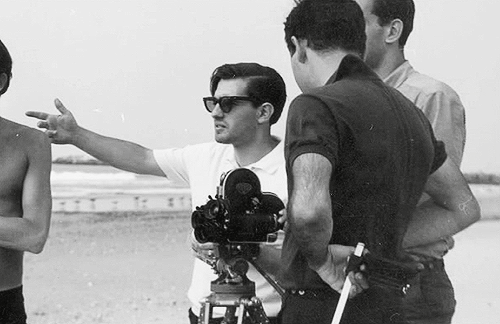

A young Scorsese directing What's A Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? (1963) |

Well, yes, he always said that the options open to him were fairly limited. He could have become a gangster, or he could have gone into the church and become a priest, but because he discovered this passion for films he decided that he would take a third route and try to become a filmmaker. So he went to film-school where he made short films like It's Not Just You, Murray!; What's a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This and The Big Shave, and he managed to get noticed. Then he made a low-budget feature called Who’s That Knocking at My Door, which grew out of one of his student shorts. Then he was hired to work on Woodstock as an editor along with Thelma Schoonmaker. Following that he made Boxcar Bertha for Roger Corman, which was sort of an exploitation picture really, though actually a rather good one. Then it was John Cassavetes who famously advised him that he should make his own films rather than somebody else’s projects. So then he started making films that were far more autobiographical and very much about the world he knew and the things he was interested in. So you got films set in New York like Mean Streets, you got films about movies like New York, New York, or about music, that reflected his passions. And he very quickly established himself as an original voice in the American cinema at the same time when Spielberg and George Lucas and De Palma were all coming along. And I think a lot of us at the time thought that Scorsese was actually the most interesting and that's probably been born out in a way. He's certainly the most enduring and probably the most consistent.

As you mentioned, Mean Streets was the first film in which Scorsese really established himself as an original new voice in American cinema. What are some of the elements, do you think, that make this film so original and unmistakably Scorsesesque?

|

Mean Streets (1973) |

I think there's a certain intensity to it that comes partly from the fact that it is about something he knows – the world he knows and the sort of people he knows – so it has a rawness that a lot of American cinema at that time didn't have. And, I mean, there was a lot of really great American cinema at that time, but Mean Streets always seemed a little bit more raw than the sort of stuff that Robert Altman, or people like Arthur Penn or Bob Rafelson were doing, and in a way rather more personal. That isn't to deny that those directors’ own films weren't personal in different ways, but the whole thing about Catholic guilt and how that fits in with more earthly desires, and the responsibility for looking after your friends who may actually be involved in things you don't actually approve of; that semi-autobiographical thing comes through very strongly. But also, of course, it was very important that he was working with Robert De Niro – that really was a match made in heaven for quite a few films. He's always worked quite closely with particular actors, but De Niro really was his dream actor for a while I think. Also there's just the sheer love of cinema and the way he uses music in the film, the way he uses camera movements and colours, and the way he references other films – like the famous fight in a bar, which was inspired by a similar fight in a Sam Fuller film. He's always filled his movies with allusions or borrowings from other movies that he likes, and he's been quite open about where those borrowings come from – it's not as if he's trying to do things without letting on; he's been quite open about it – but I think he does it in rather a more interesting way than someone like Tarantino. With Tarantino there's a slight side of him that wants to show off how hip he is, but with Scorsese the allusions and borrowings are more closely woven in to the narrative

Scorsese’s next film was Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, which was well-received but was something of a departure for him. But then he returned to New York to make Taxi Driver which was one of his most controversial but also most popular films, and for many this is still their favourite Scorsese movie. What do you think it is about Taxi Driver that continues to resonate so much with people?

|

Scorsese directs Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver (1975) |

Well, it's funny, I was writing the notes for our booklet on this film – I'm not sure if it was before Trump's victory or just after – but it felt incredibly relevant. The sense that there might be somebody out there who's deeply alienated and listening to all sorts of propaganda messages and rhetoric, and you don't know what's going on in their head, who could end up doing something really horrible. So I do think Taxi Driver is quite prescient in some ways and it still feels very relevant in that respect, perhaps more now than it did ten years ago. And it's interesting that when Travis Bickle does take interest in a girl, she’s actually somebody who's working for a campaign for a political candidate. So that's always resonated strongly for people and it's certainly one of the reasons why the film has lasted so long. But also, perhaps even more so than Mean Streets, Scorsese's real cinephilia comes through. From the opening credits, where you've got this yellow cab going along in slow motion and the smoke billowing out on the streets; it's a vision of hell on earth. And, of course, it benefits from having a great script by Paul Schrader as well, and another wonderful De Niro performance. But it's really Scorsese firing on all cylinders: the use of slow motion in certain scenes; the use of colour; the very famous scene where you've got De Niro talking to himself in the mirror; the cutting that he uses. I think, having been around at that time watching films, that there were other directors doing really interesting things – I've mentioned Altman and De Palma and Spielberg and Arthur Penn – but I think Scorsese was more up front about cinematic style. And when he uses style it's nearly always at the service of the content; it does actually tell us something, he's not just showing off. And you get a real sense of Travis Bickle's fragmented sense of reality, this detachment from reality.

It’s fascinating how Scorsese controls viewpoint in the film, shifting between a kind of objective documentary-style realism and a more subjective expressionistic style.

Yes, absolutely. I do think of Scorsese as an expressionist really. He’s very good at using the camera and the sound and the music and cutting to put us inside the heads of his characters, and also to see how they are shaped and how they interact with society around them.

Throughout the seventies and up to the present Scorsese has made documentaries alongside his features, many of which will be showing in this retrospective. Can you talk a little bit about the documentaries – do you think they’re an important part of his output?

|

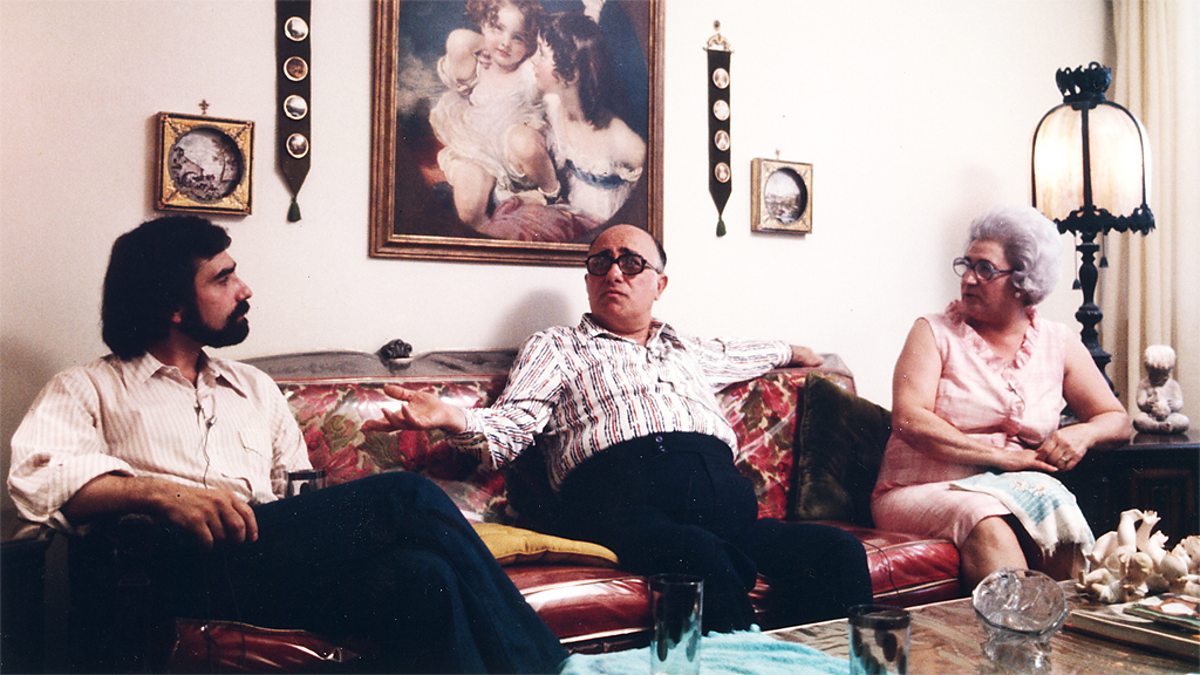

Scorsese with his parents on the set of Italianamerican (1975) |

I think they are because they often help us understand the features in a way. I mean Italianamerican is about his parents; the two of them sit on a sofa and talk for a bit. And from that we see where Marty came from, and the sort of world he grew up in, and where he got his talkativeness from. And then there’s American Boy which is about Stephen Prince – the guy who plays the gun trader in Taxi Driver – and again it shows Scorsese’s then fascination with violence. I do think he’s lost that fascination now having grown older and matured, but he certainly had a very ambivalent attitude towards violence in those early films. And as time has gone on his documentaries have become, still about him, but they relate to his passions: so he’s made films about film history and about music people that he likes. I also really like the recent one about The New York Review of Books called The Fifty Year Argument. So I do think we learn quite a lot about where he’s coming from.

In 1979 Scorsese made Raging Bull about the boxer Jake la Motta. The violence in the film is often visceral and difficult to watch, and the main character is not at all likeable. But it’s a film that people love and some people consider it one of the greatest films ever made. What would you say are the skills that Scorsese brings to his filmmaking in a work like this that make it so compelling and watchable?

|

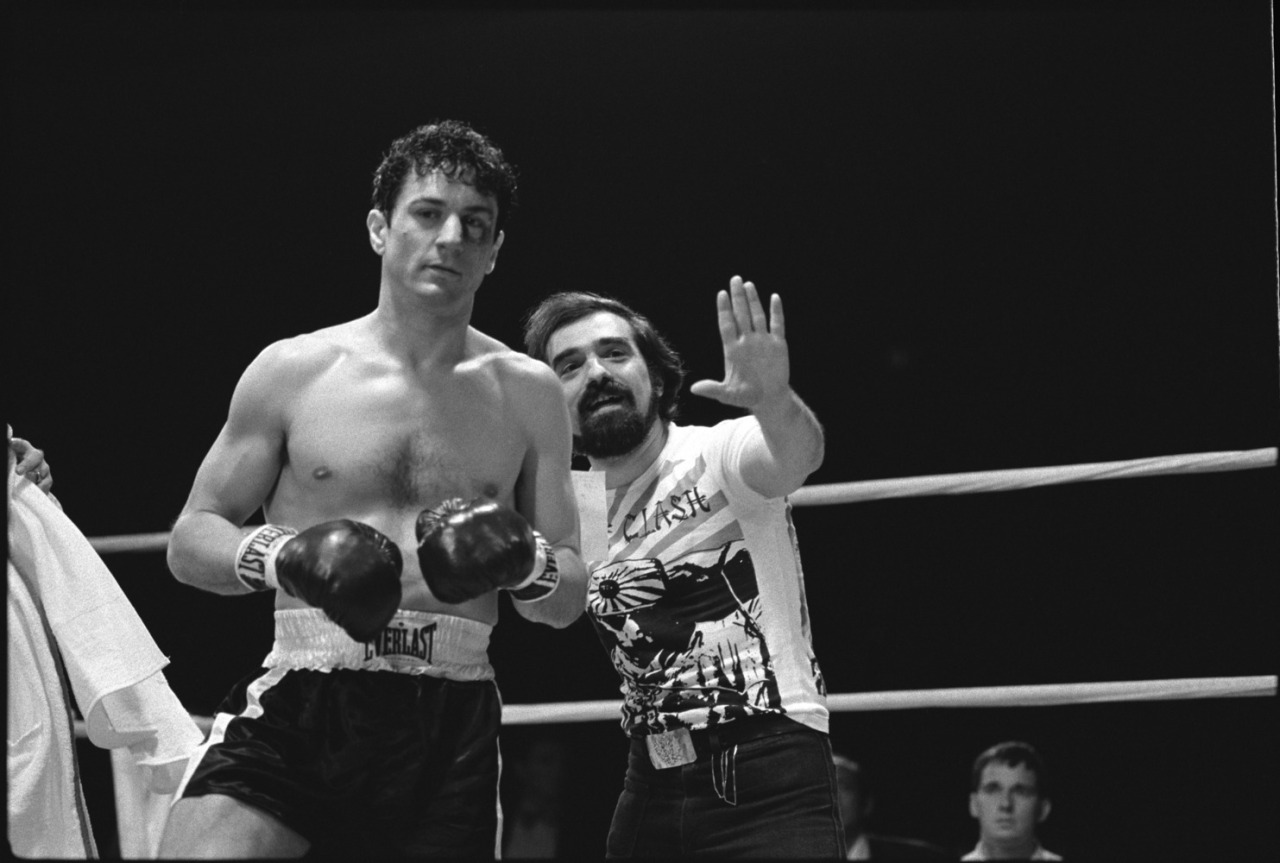

Scorsese directing De Niro again, this time in Raging Bull (1980) |

Yes I do think it’s a greater film than Taxi Driver or Mean Streets. I think the really great thing about Raging Bull is that it’s here that he’s really beginning to lose his fascination with violence, although La Motta is presented as a very violent person. I mean the violence is ugly in this film, not only in the ring, but also directed against women. But he manages, with no little help from Robert De Niro, to make this rather monstrous man still very much a person that we should think about and ask: why is he like this? I also think it’s one of the great American films about masculinity, particularly about masculine insecurity and neurosis. It also shows how people who can’t express themselves well – because they haven’t had the right upbringing, or education, or whatever; or because they’re part of a certain sort of society or culture – if they can’t express their anger and frustration verbally, then they often find other ways of doing it, and I think that’s what we see with La Motta in this film. He’s very much a human being, a fairly awful one maybe, but we have to accept that people like this do exist. And Scorsese manages, as you said, to make a film about somebody who’s not very sympathetic, but who still calls upon our attention. I mean, the last time we spoke we were talking about Eric Rohmer and he did something similar with The Green Ray, which is a film about somebody who’s actually very intensely irritating a lot of the time, but we’re made to feel for them and to understand them. And I think Scorsese, in a very different way, does that with Jake La Motta. And quite often those are the sort of films that are really special because the American mainstream – Hollywood or whatever you want to call it – usually specializes in making films where we root for somebody. It’s heroic drama usually and actually usually very simplistic. But, I think, Scorsese has consistently made us wonder about his protagonists and ask: are they heroes or are they villains? Sometimes I think he himself is confused as to which they are, but I think in a film like Raging Bull he got it absolutely right

Scorsese has always been interested in religion and spiritual questions, particularly in films like The Last Temptation of Christ, Kundun, and in his new film Silence. Can you talk about how important spirituality is as an ongoing theme in his work?

Yes, I think it is there quite a lot, but I think we shouldn’t overemphasize it. I mean, a few people have – there was an exhibition at the Cinémathèque Francais where it pointed out how many images there are in Scorsese films that are reminiscent of the crucifixion from Boxcar Bertha onwards – but I don’t think spirituality comes up that much really in Scorsese’s work. Certainly there’s a little bit of it in Mean Streets, but that’s more about pure Catholicism and whether you can you ever not be a Catholic and loose your Catholicism? Spirituality is certainly there in Last Temptation of Christ and Kundun, and indeed in the new one Silence, but I don’t think it’s giving away too much to say his new film is by far his most philosophical film yet and it is an extended exploration of faith. What responsibility that entails and where does it come from and how does it operate in a world that challenges your faith all the time. So it’s an element in some of his films but I think it would be wrong to read too much into them.

Lastly, I wanted to ask if you had a favourite Scorsese film and why?

|

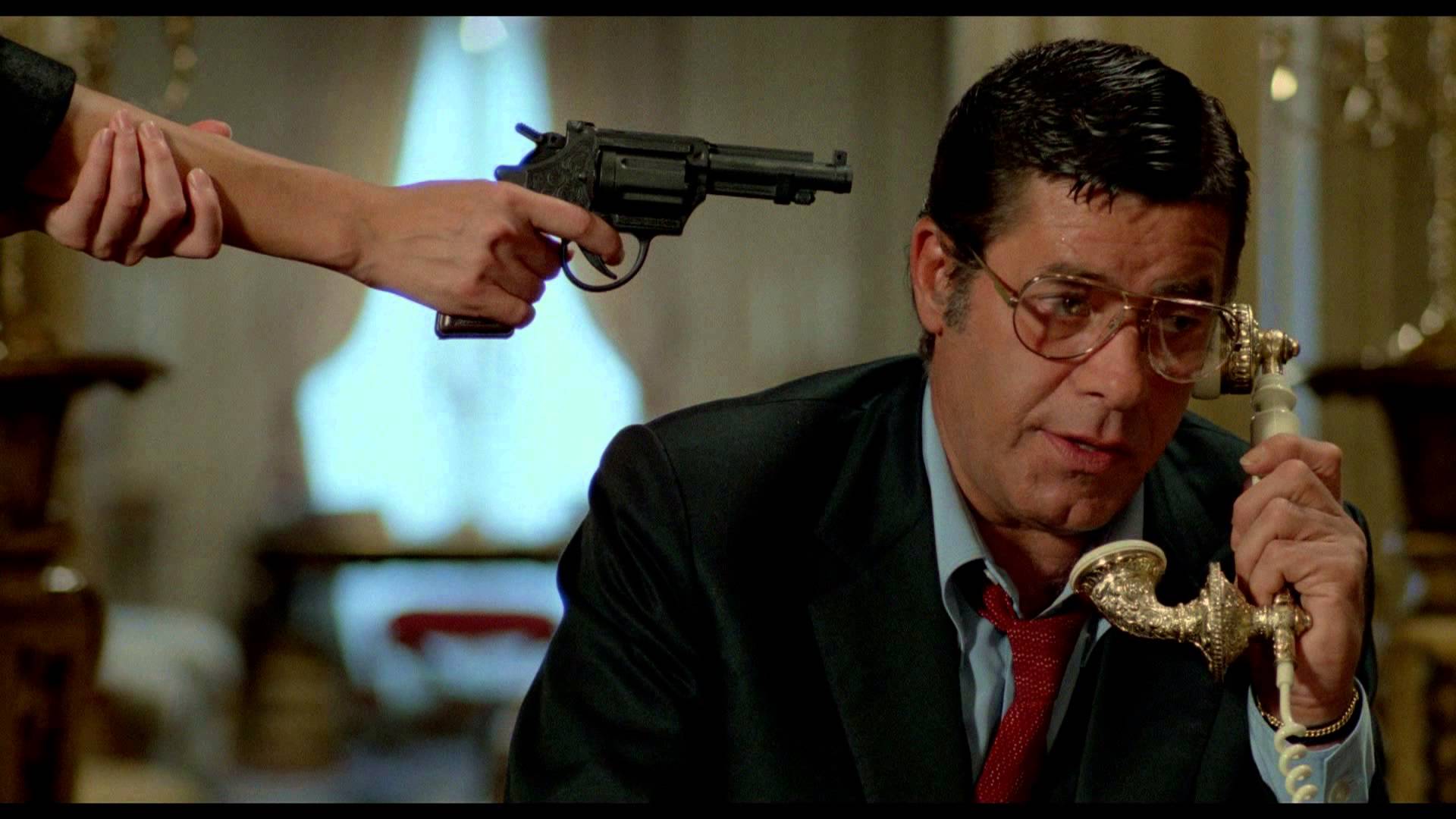

Jerry Lewis in King of Comedy (1982) |

I always tend to mention King of Comedy and Age of Innocence, both of which I think are amongst his very best films and actually quite underrated. I remember King of Comedy coming out and I remember it slightly bemused people. Before that with Taxi Driver and New York, New York, Scorsese had been moving the camera around all over the place and a lot of King of Comedy was shot with a static camera. Actually I think the camera style in that film and the cutting are absolutely perfect but it was unexpected. And also it was called King of Comedy and it was sort of funny but in a very creepy way. Also it’s a very adventurous film, and actually very prescient, you know, just as prescient as Taxi Driver, and in fact more so because it’s concerned with celebrity and the inability of people to distinguish between what they see on television and the world they actually live in. I think Age of Innocence is underrated for different reasons. I think in its own way it’s just as concerned with violence as many of his other films, but it’s violence of a very different sort, which is expressed through words and control and through very strict social codes. And again the style is really perfect for what the film is doing, which is to create this sense of oppression in this well-to-do society, which is almost stifling some of the time. And it sort of shows that Scorsese didn’t need De Niro to have great performances. I mean Day Lewis is great, Day Lewis is great in a lot of things, but Scorsese also got a wonderful performance out of Michelle Pfeiffer, which is perhaps a little more surprising, and Winona Ryder as well. I mean, I’m not saying they’re not great actresses, but where are their other really great performances? There’s not that many of them. But Scorsese did that and I think it’s a work of great subtlety. So I think those two, for me, along with Raging Bull, are probably the three great Scorsese films.

Interview by Simon Hitchman, © December 2016 - please do not reprint or reuse without permission. |