|

To enjoy 2-for-1 tickets to any films in the season simply quote when ordering tickets via phone or the BFI website.

|

La Terra Trema (Luchino Visconti, 1948) |

1. As the curator of this two-month Italian Neorealism retrospective at the BFI, can you give a brief overview of what the season will include and recommend some highlights for our readers?

In this two-month retrospective we’ll show 20 titles of the best Italian cinema from one of the most crucial decades in film history. The season will include some canonical titles as well as lesser-known gems that haven’t been screened in UK in decades (some never before, as far as I could track down), so audiences will be able to rediscover or discover for the first time these seminal films on the big screen and on the best available formats. There will be some new 4K restorations and a few 35mm prints imported from Cinecittà. Some highlights include the classics, such as Rossellini’s “War Trilogy” (Rome, Open City, Paisà and Germany Year Zero) and Visconti’s La Terra Trema, but also works by the often-overlooked Giuseppe De Santis (A Tragic Hunt; Rome 11:00) and Alberto Lattuada (The Bandit).

2. What do you feel were the primary circumstances or influences that led to the emergence of Neorealism in the years following WWII.

Neorealism was the response to a very specific moment in Italian history. In 1945, after the Liberation, most of Italy (and Europe) was in ruins. After 20 years of fascist dictatorship, Italians, liberated from the censorship of the regime, were keen to break all ties with the past. In politics this was known as “Italian spring”. The film industry, which at that point was in a state of complete chaos, came to play an important role in the rebirth of Italy: filmmakers could finally focus on contemporary social problems such as divisions in society, poverty and unemployment. Reality appeared on screen for the first time.

|

Rosselini directing Rome, Open City (1945) |

3. Can you talk a bit about the defining features or hallmarks of Italian neorealism in terms of storytelling, cinematography, and character portrayal, and how the movement challenged or departed from the traditional filmmaking practices of its time?

Neorealists wanted to represent the lower classes of Italian society, bringing to the centre of the scene problems and characters that had never been the subjects in Italian cinema up to that point - dominated as it had been by “white-telephone” comedies and historical triumphant films.

The “innovations” that are usually associated with neorealism had already emerged previously, but the international distinction of the movement outlined these aspects as it hadn’t been done before. The defining hallmarks vary greatly depending on the directors and scriptwriters, but often included: shooting on location, a mix of professional and non-professional actors, a willingness to improvise scripts (Rossellini mostly), colloquial dialogue (often dialect), dubbing in post-production, ellipses, micro-actions, open endings, exasperate variation of tones and implied or open social criticism.

However, these can also be challenged as commonplaces: many neorealist films relied on the performances by highly experienced actors, shooting often used studio sets and these films were not made on a particularly low budget. As Italian neorealism never formed a coherent movement or group, there were very different styles, which created many different “neorealisms”.

|

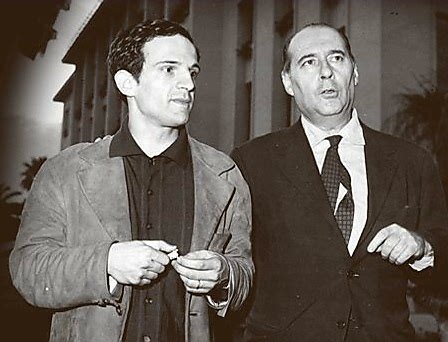

Vittorio De Sica & Cesare Zavattini

|

4. Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, and Luchino Visconti are considered to be the three most important Italian neorealist directors. Can you talk about the similarities and differences between these three directors in their style and approach to directing.

The three canonical directors - Rossellini, Visconti and De Sica - couldn’t have been more different in their style and approach to directing. They were united mostly in the name of a new moral position towards reality. As Rossellini said: “There are many kinds of neorealism; everyone has his own.” He blended fiction and actuality into his unvarnished form of neorealism with a rough-edged aesthetic, while Visconti’s work was renowned for its classic beauty and scale, its compositional rigour, indebted to naturalist tradition. On the other hand, De Sica, whose neorealist work is inseparable from his scriptwriter Cesare Zavattini’s, made deeply humanistic films with rigorously structured screenplays. One thing they all share is that, as Cesare Zavattini put it, “we want, all together, to purify and renew”.

|

Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948) |

5. Could you highlight a few landmark films that epitomize the essence of Italian neorealism and explain their significance?

Many of the titles in the season can be considered landmark films but the key titles here are definitely Rome, Open City (1945), which the BFI are re-releasing at selected cinemas UK-wide as part of the season, Bicycle Thieves (1948) and La terra trema (1948), respectively by Rossellini, De Sica and Visconti. Individually, these are landmarks for different aspects of neorealism but overall they are particularly significant as, each in its own way, they represent the “purest” examples of neorealism (if such a thing even existed) in the crucial years 1944 – 1948, before the Andreotti law of 1949 (from the US-backed Christian Democracy party) forced the exhaustion of the neorealist impulse. After that, the main auteurs took a different direction: Miracle in Milan (1951) by De Sica is in this context a remarkable example of one of the variations that evolved from neorealism, magic neorealism, in which fantastical and supernatural elements blend with evocations of everyday life.

|

The Bandit (Alberto Lattuada, 1946) |

6. You’ve included some lesser-known directors and films in the season, can you talk a little more about these films and how they broaden our understanding of neorealism?

There are two overlooked directors that I included in the season that deserve to be better known: Giuseppe De Santis and Alberto Lattuada. They both have been only rarely celebrated in retrospectives but more often simply forgotten, unjustly. De Santis, who started as a film critic, understood that through cinema he could communicate directly to the people he cared most about: the peasants, the workers (see A Tragic Hunt). Lattuada, whose career traversed more than four decades of Italian cinema, expanded the boundaries of neorealism blending it with popular storytelling (see The Bandit and The Mill on the Po). Both directors experimented with genres and assimilated American and Soviet influences, injecting noir tension and melodrama into neorealism.

7. How was Italian neorealism received initially, both domestically and internationally? Were there any significant challenges or criticisms it faced?

Most of these neorealist classics were overlooked when they were released in Italy and, initially, they were box office failures (despite critical success). At the beginning, with Rome, Open City, for audiences it was too early to talk about those stories: the daily fight for survival of the characters was too close to the lives of the actual people on the streets. When the first American films started reappearing in Italy after the war, audiences wanted escapism and were completely uninterested in the reality of what was going on in Italy. But when these reached international audiences, they were major successes, gathering Oscar nominations (and winning in various cases). Thanks to the international recognition the success of the films bounced back to Italy, where they were eventually acknowledged as masterpieces.

|

Truffaut & Rosselini |

8. What impact did Italian neorealism have on the global cinematic landscape and on subsequent generations of filmmakers such as the French New Wave?

Neorealism had a profound and ramified influence in most international cinema: it spread across the world, radically transforming the cinematic landscape worldwide. Its impact can be found in most of the national waves that came after it, such as French New Wave, the Cinema Novo of Brazil, the Third Cinema of Argentina, the Free Cinema in Britain, the Mexican films of Buñuel (such as Los Olvidados, 1950), Satyajit Ray and Indian Parallel Cinema, the Polish Film School, and the list goes on to the present day in the films from countries with extremely strict censorship codes like Iran (ie Neorealism, Iranian style).

The auteurs of the French New Wave were greatly inspired by Italian neorealism, particularly the films of Roberto Rossellini, although they had an ambiguous relationship with neorealism of dependence and contrast, of admiration and aversion.

9. Have there been shifts in critical perception or understanding of neorealist films over time?

The animated critical debate that neorealism sparked began with the release of Rome, Open City in 1945 and continued into the ‘50s. In Italy neorealist films were frequently greeted with hostility by Catholic critics and in some cases boycotted by exhibitors under pressure from the government. Luckily, the reception abroad was different and free from the influence of the Catholic church, which allowed them to be recognised internationally for their inestimable contribution to cinema. The critical understanding of neorealist films over time has demystified some of the most common misconceptions and generalisations around neorealism. Some of the myths have been challenged, which showed even more clearly how these were films of contrasts and not reducible to a coherent set of principles.

|

Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945) |

10. Finally, I wondered what draws you personally to the films of the Italian neorealism movement? Are there any particular neorealist films or filmmakers that have left a lasting impact on you and why?

As Italians, neorealism is rooted in who we are, it’s inextricably part of us, historically but even visually, of our shared culture. So, as an immigrant in the UK, going back to these films, was like a homecoming in a way. Researching and selecting the films for the season gave me the chance to revisit them from a new perspective. It was especially revelatory rewatching Rome, Open City, still so relevant today, almost 80 years later.

Interview by Simon Hitchman, © May 2024 - please do not reprint or reuse without permission. |