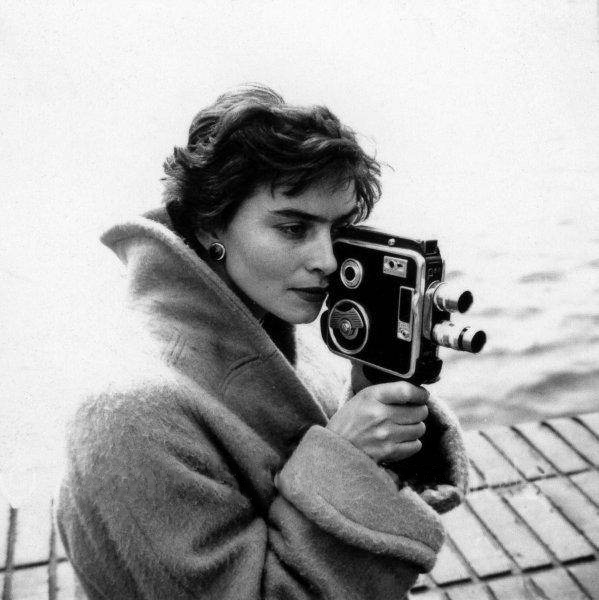

Czech New Wave directors including Vera Chytilova (center), Milos Forman

Czech New Wave directors including Vera Chytilova (center), Milos Forman

(second from right), Evald Schorm (to his left), and Jiri Menzel (far right).

The Czechoslovak New Wave was a cinematic movement that emerged in the 1960s. It was characterized by bold and experimental storytelling, a focus on social and political issues, and a dedication to exploring personal freedom and individual expression. This movement developed within the broader context of the political liberalization occurring during the 1960s in Czechoslovakia, culminating in the Prague Spring of 1968. |

|

Key Czech New Wave Directors |

Their Key Films of the Period |

| Věra Chytilová |

Something Different (1963)

Daisies (1966)

Fruit of Paradise (1969) |

| Evald Schorm |

Courage for Every Day (1964)

The Return of the Prodigal Son (1967)

End of a Priest (1969) |

| Miloš Forman |

Black Peter (1964)

Loves of a Blonde (1965)

The Firemen's Ball (1967) |

| Ivan Passer |

Intimate Lightning (1965) |

| Jaromil Jireš |

The Cry (1963)

The Joke (1969)

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970) |

| Jan Němec |

Diamonds of the Night (1964)

A Report on the Party and the Guests (1966)

Martyrs of Love (1967) |

| Jiří Menzel |

Closely Watched Trains (1966)

Capricious Summer (1968)

Larks on a Train (1969) |

|

|

Historical Background

1948 Czechoslovak coup d’état

|

Post-War Czechoslovakia and Communism: After World War II, Czechoslovakia was re-established as an independent state but fell under Soviet influence in 1948 following a Communist coup d'état. For over a decade, the country was tightly controlled by the Communist Party, with censorship imposed on the arts. During the early years of Communist rule, film was used as a tool for socialist propaganda, adhering to the strict guidelines of Socialist Realism, which emphasized ideological purity, heroism, and a positive depiction of the proletariat. However, by the 1960s, political and cultural tensions were mounting, giving way to a loosening of restrictions, especially in the arts.

The Thaw and Political Liberalization: The political changes in Czechoslovakia were closely linked to the broader liberalization movements happening in Eastern Europe, particularly the Soviet Union's Khrushchev Thaw. In Czechoslovakia, the early 1960s saw the rise of a younger, more critical generation of filmmakers who had grown frustrated with the limitations imposed by the government. This coincided with a cultural renaissance in literature, theatre, and art, as intellectuals and artists began pushing the boundaries of what could be expressed under the Communist regime.

The catalyst for the New Wave was the relatively progressive leadership of Czechoslovak President Antonín Novotný, who, despite being a Communist hardliner, allowed for a brief period of cultural openness in the 1960s. This era culminated in the Prague Spring of 1968, a period of political and social reform under Alexander Dubček, who sought to create "socialism with a human face." Although the Prague Spring was short-lived due to the Warsaw Pact invasion in August 1968, the Czechoslovak New Wave had already made a profound impact on world cinema.

Cinematic Background

Jan Hus [1954]

|

During the 1950s, Czechoslovak cinema was dominated by state-approved films that often glorified socialism. These included Otaker Vávra's trilogy Jan Hus (1954), Jan Žižka (1955), and Against All (1956), historical epics about national heroes. However, many filmmakers found this style creatively stifling, and a growing sense of dissatisfaction began to permeate the industry.

By the late 1950s, a new generation of filmmakers, influenced by the political thaw following Stalin's death in 1953, began pushing back against the rigid constraints of socialist realism. This period, known as the "Cultural Spring," allowed for more creative freedom, with artists and intellectuals beginning to question the status quo and explore new forms of expression.

Key to this transition was the establishment of the Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts (FAMU) in Prague, one of the oldest film schools in the world. FAMU became a breeding ground for young, experimental filmmakers who would eventually spearhead the Czech New Wave. Directors such as Miloš Forman, Věra Chytilová, Jiří Menzel, and Jan Němec studied at FAMU and were heavily influenced by the works of European auteurs like Jean-Luc Godard and Federico Fellini, as well as the Italian Neorealist movement. These young directors sought to break away from the propagandistic formulas of the past, favouring personal, unconventional, and often politically subversive narratives.

The Sun in a Net [1963]

|

During this time, a number of important films were made that hinted at the forthcoming revolution in Czechoslovak cinema. One such film was The Sun in a Net (1963) by Štefan Uher, which is often cited as the first example of the Czech New Wave. Its realistic portrayal of everyday life, combined with innovative narrative techniques and a focus on personal rather than collective experiences, represented a significant break from the socialist realist tradition. The film's exploration of emotional and existential themes resonated with a generation of young people disillusioned by the rigid structures of Communist society.

The Emergence of the Czechoslovak New Wave in the 1960s

By the early 1960s, Czechoslovakia's political climate had softened, allowing for more openness in cultural production. The Czech New Wave, emerging in this context, was characterized by its rejection of traditional cinematic conventions and its embrace of experimental narrative structures, naturalistic performances, and a deep sense of irony and absurdity. Influenced by the French New Wave, Italian Neorealism, and other international movements, the films of this era often tackled themes of political repression, existentialism, and personal freedom.

The Czechoslovak New Wave: Leading directors and their films

The directors discussed below were predominantly born in the 1930s, with Věra Chytilová (born in 1929) being the sole exception. They emerged as key figures of the Czechoslovak New Wave, making their debut feature films in or around 1963—the year widely regarded as the movement’s official starting point. Each of these filmmakers studied at FAMU, where they honed their craft and developed the distinctive artistic sensibilities that would come to define the movement.

Additionally, under each director is s a curated list of their films frequently considered part of the Czechoslovak New Wave. These films either contributed to the early development of the movement, were released toward its later years, or hold particular significance in understanding the broader evolution of Czechoslovak cinema during this transformative period.

Věra Chytilová

"You don't really begin working creatively until you are at a point where you don't know."

Věra Chytilová

|

Věra Chytilová was one of the most innovative and provocative filmmakers of the Czech New Wave, known for her avant-garde style and fearless critique of social conventions. As one of the few prominent female directors of the movement, Chytilová carved out a unique voice in a male-dominated industry, pushing the boundaries of cinematic form and narrative with her bold, experimental approach. Her films, particularly from the 1960s, reflected the radical spirit of the time, blending surrealism, satire, and feminist commentary to address the absurdities of life under socialism and the restrictive roles imposed on women by society.

Věra Chytilová was born on February 2, 1929, in Ostrava, Czechoslovakia, and grew up in a middle-class family. Initially, she studied philosophy and architecture in Prague but soon found her true passion in film. After various jobs, including working as a fashion model, she applied to the prestigious film school FAMU in Prague, where she was admitted despite initial rejections. At FAMU, Chytilová trained under notable filmmakers and honed her craft, becoming part of a new generation of directors who would later lead the Czech New Wave. She developed an unconventional and radical style early on, focusing on social criticism and gender issues and pushing the boundaries of cinematic form. These elements would define her career as one of Czech cinema's most important and provocative voices.

Something Different (1963)

Věra Chytilová's feature debut, Something Different (O něčem jiném), was an early indication of her radical style and thematic focus on women's lives. The film is a split narrative that intertwines the stories of two women, one a professional gymnast training for competition and the other a housewife stuck in the mundane routine of domestic life. Through parallel editing, Chytilová juxtaposes the physical rigor and discipline of the gymnast with the emotional monotony of the housewife, creating a subtle yet powerful commentary on the roles women are expected to play in society.

Daisies [1966]

|

Daisies (1966)

Chytilová's most iconic and internationally celebrated film, Daisies (Sedmikrásky), is a dazzling and subversive work that exemplifies the spirit of the Czech New Wave. Released in 1966, the film follows two young women, both named Marie, who engage in a series of anarchic pranks and indulgent behavior as a form of rebellion against the conformist, patriarchal society they live in. The film's narrative is loose and fragmented, with the characters gleefully defying logic and convention as they wreak havoc on social order, playing with food, men, and societal rules with reckless abandon.

Daisies is celebrated for its avant-garde style, characterized by bold visual experimentation, rapid editing, and surrealist imagery. Chytilová employed a wide range of cinematic techniques, including colour filters, collage effects, and abrupt changes in tone and style, to create a playful yet subversive critique of the emptiness and absurdity of consumerism and authoritarianism. The film also contains a strong feminist undercurrent, with the Maries' refusal to conform to traditional female roles challenging the objectification and control of women in society.

Despite its anarchic spirit and humour, Daisies was not without controversy. The Czechoslovak government saw the film's irreverent tone and anti-authoritarian message as a political threat. Its depiction of waste, particularly in scenes involving the destruction of food, was viewed as an affront to the communist regime's values. As a result, Daisies was banned for a time, though it gained international recognition and became a cult classic, winning the Grand Prix at the Bergamo Film Festival in Italy. Today, Daisies is considered one of the masterpieces of the Czech New Wave and a pioneering work in feminist cinema.

Fruit of Paradise (1969)

Following the international success of Daisies, Chytilová continued her experimental approach with Fruit of Paradise (Ovoce stromů rajských jíme, 1969). This film, loosely based on the biblical story of Adam and Eve, is another visually striking work that delves into philosophical and existential questions about knowledge, temptation, and freedom. Set in a surreal, dreamlike world, the film follows Eva as she becomes increasingly obsessed with uncovering the truth about her surroundings and the mysterious man she encounters, leading her to confront the limits of knowledge and human desire.

Like Daisies, Fruit of Paradise was marked by its unconventional narrative structure and visual experimentation. Chytilová used abstract imagery, fragmented editing, and symbolic motifs to create an atmosphere of uncertainty and ambiguity, reflecting the growing sense of disillusionment in Czechoslovakia following the Prague Spring and the subsequent Soviet invasion in 1968. The film's allegorical nature allowed Chytilová to explore themes of control and resistance, as well as the complexities of human relationships and the pursuit of forbidden knowledge.

Evald Schorm

“The world is terrifying, and yet it is beautiful, and that’s how it is with everything; things exist so close together, that between love and cruelty, between one thing and another there is but a tiny, negligible distance.”

Evlad Schorm

|

Evald Schorm was one of the most distinctive voices of the Czechoslovak New Wave, known for his deeply introspective and morally probing films. Unlike some of his contemporaries who leaned toward satire or absurdism, Schorm’s work was marked by a serious, almost philosophical engagement with themes of personal responsibility, faith, and existential uncertainty. His films, such as Courage for Every Day (1964) and The Return of the Prodigal Son (1967), explored the struggles of individuals caught between personal conscience and societal expectations, reflecting the growing disillusionment of the 1960s. With a restrained visual style and emotionally charged performances, Schorm captured the anxieties of a generation navigating the contradictions of life under communism.

Born in 1931 in Prague, Schorm came of age in a period of political upheaval and trained as a filmmaker at FAMU. Unlike his more internationally recognized peers, his career was tragically curtailed following the 1968 Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia. His uncompromising vision led to his effective blacklisting from cinema, forcing him to shift his creative energy toward theater and opera directing. Despite this suppression, his influence endured, and his films remain some of the most powerful examinations of moral and spiritual crisis in Czech cinema. Schorm’s legacy is that of a filmmaker who, even in silence, left an indelible mark on the artistic and intellectual life of his country.

Courage for Every Day (1964)

Evald Schorm’s Courage for Every Day (Každý den odvahu) is a key work of the Czechoslovak New Wave, reflecting the disillusionment of postwar socialist idealism. The film follows a devoted communist worker, Jarda, whose faith in the socialist system is tested as he watches his fellow comrades abandon the ideals of collectivism in favor of individualism and personal gain. Through Jarda’s struggles, Schorm critiques the rigid ideology of the regime and highlights the emotional toll of ideological disillusionment. The film’s raw, neorealist aesthetic and introspective character study distinguish it as one of the more poignant explorations of moral and political crisis in 1960s Czechoslovak cinema.

Schorm’s direction imbues the film with a sense of melancholy and existential questioning, elements that became central to his work. The cinematography, favoring stark compositions and naturalistic settings, underscores Jarda’s growing isolation and internal conflict. Unlike some of his contemporaries who used irony or surrealism, Schorm adopts a more serious, contemplative tone, making Courage for Every Day a sobering reflection on the fading optimism of the early socialist period. The film was banned after the Soviet invasion of 1968, further cementing its status as a politically charged and socially critical work.

The Return of the Prodigal Son (1967)

|

The Return of the Prodigal Son (1967)

In The Return of the Prodigal Son (Návrat ztraceného syna), Evald Schorm crafts an intimate psychological drama that delves into themes of existential despair and social alienation. The film follows Jan, an architect who, after a failed suicide attempt, is placed in a psychiatric hospital, where he confronts the emptiness of his life and the limitations imposed by both his personal choices and the surrounding society. Through Jan’s interactions with doctors, family members, and fellow patients, Schorm presents a haunting portrait of an individual trapped in a world that stifles both personal and artistic expression.

Schorm’s austere visual style enhances the film’s introspective mood, using stark, almost documentary-like cinematography to emphasize the protagonist’s psychological turmoil. The performances, especially Jan Kačer’s portrayal of the tormented Jan, add to the film’s emotional depth, making it a deeply affecting study of human fragility. The Return of the Prodigal Son remains one of Schorm’s most powerful works, offering a bleak yet profoundly humanistic meditation on identity, freedom, and the inability to escape one’s own existential burdens.

End of a Priest (1969)

Schorm’s End of a Priest (Farářův konec) departs from his previous somber realism and ventures into satire, blending absurdist humor with a biting critique of social hypocrisy. The film tells the story of an ordinary man who is mistakenly believed to be a Catholic priest and decides to embrace the role, quickly gaining the admiration of the townspeople. However, his deception soon leads to unforeseen consequences, exposing the contradictions and moral failings of both religious institutions and the broader community. Through its ironic premise, the film critiques the mechanisms of authority, belief, and societal expectations, drawing on influences from both Kafkaesque absurdity and Brechtian theatricality.

Unlike the psychological realism of Courage for Every Day and The Return of the Prodigal Son, End of a Priest employs a more stylized, exaggerated aesthetic. Schorm uses humor as a subversive tool, highlighting the absurdity of rigid social structures and the ease with which people accept constructed identities. The film’s irreverent tone and sharp critique made it controversial, especially in the political climate of post-1968 Czechoslovakia, leading to its suppression. Yet, it remains an essential part of Schorm’s filmography, demonstrating his versatility as a filmmaker and his ability to challenge societal norms through both tragedy and satire.

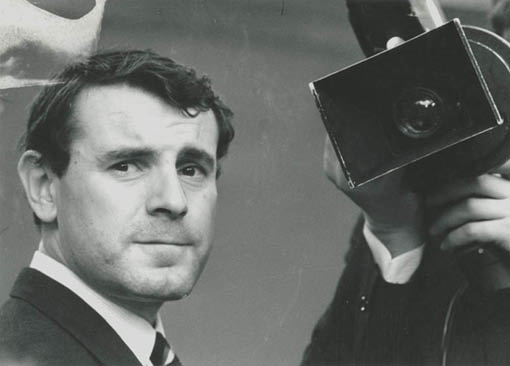

Miloš Forman

"Humor was not important only for me, humor was important for this nation for centuries, to survive, you know."

Miloš Forman

|

Miloš Forman, one of the most influential directors of the 20th century, played a key role in the rise of the Czechoslovak New Wave in the 1960s. Known for his sharp, humanistic storytelling and subtle satire, Forman became a defining voice of the movement with a handful of films that critiqued the absurdities of life under communist rule. His blend of realism, dark humour, and compassionate portrayals of flawed characters made him a standout figure not only in Czechoslovak cinema but also in the wider world of international filmmaking.

Miloš Forman was born in 1932 in Čáslav, Czechoslovakia, and experienced a tumultuous childhood. Both of his parents perished during World War II in Nazi concentration camps, an event that left a profound mark on Forman's outlook on life. After the war, he studied screenwriting at FAMU in Prague, where many future New Wave directors honed their craft. Inspired by Charlie Chaplin, Italian Neorealism, the French New Wave and cinéma vérité, Forman crafted a realistic style that highlighted the struggles of everyday people while offering darkly comic critiques of authority and societal norms.

Black Peter (1964)

Forman's first major film, Black Peter (Černý Petr, 1964), was a milestone in both his career and the Czechoslovak New Wave. The film tells the story of a shy, introverted teenage boy, Petr, who begins a summer job as a shop assistant. His primary responsibility is to catch shoplifters, but Petr is too timid and unsure of himself to confront anyone. Set against the backdrop of a small town, the film examines the awkwardness and confusion of adolescence, focusing on themes of youthful disillusionment, generational conflict, and the mundane realities of life under a rigid, authoritarian regime.

Black Peter was ground-breaking for its naturalistic performances, use of non-professional actors, and observational style. Forman portrayed everyday life in a fresh and immediate way, with a subtle critique of social expectations and the petty bureaucracies that governed daily life in communist Czechoslovakia. The film was both a domestic and international success, earning the Golden Leopard at the Locarno Film Festival in Switzerland and establishing Forman's status as a key figure in the emerging Czech New Wave.

Loves of a Blonde (1965)

|

Loves of a Blonde (1965)

Forman followed up Black Peter with the critically acclaimed Loves of a Blonde (Lásky jedné plavovlásky, 1965), a film that further cemented his reputation as a master of humanistic comedy and social critique. The story centers on Andula, a young factory worker in a small Czech town, who falls in love with Milda, a visiting pianist from Prague. After a brief affair, she travels to the capital city to surprise Milda, only to find herself unwelcome in his home and uncomfortably caught between her dreams and the harsh reality of life.

Loves of a Blonde showcased Forman's gift for blending humor with pathos, and it offered a satirical look at the social and emotional isolation of individuals in a highly controlled society. Its naturalistic style, intimate performances, and emphasis on small, seemingly insignificant moments were trademarks of the realist strain of the Czech New Wave, of which Forman was the leading exponent. Like Black Peter, Loves of a Blonde used non-professional actors alongside seasoned performers, contributing to its sense of authenticity. The film's bittersweet tone and critique of the conformist pressures placed on young women in communist society resonated with audiences both in Czechoslovakia and abroad. Loves of a Blonde was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and received widespread praise at the Venice Film Festival.

The Firemen's Ball (1967)

In 1967, Forman released The Firemen's Ball (Hoří, má panenko), a biting satirical comedy that skewers the incompetence and absurdity of bureaucracy. The film is set in a small provincial town, where a group of firemen organize a gala event that quickly descends into chaos. The firemen's well-intentioned attempts to throw a respectable ball are undermined by petty infighting, corruption, and a series of comical mishaps, including a disastrous beauty contest and a fire that the firemen fail to control.

The Firemen's Ball was Forman's most overtly political film, using the firemen as an allegory for the inefficiency and corruption of the communist system. The film's humor comes from the gap between the firemen's self-importance and their sheer incompetence, reflecting the absurdities of life under an authoritarian government. Despite its comic tone, The Firemen's Ball was a daring critique of the political system, and its subversive message did not go unnoticed by authorities.

Although the film was banned in Czechoslovakia following the Soviet invasion in 1968, it became an international sensation and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Its sharp satire and naturalistic ensemble performances made it one of the defining works of the Czech New Wave, as well as one of the last films Forman made in his homeland before his emigration to the United States.

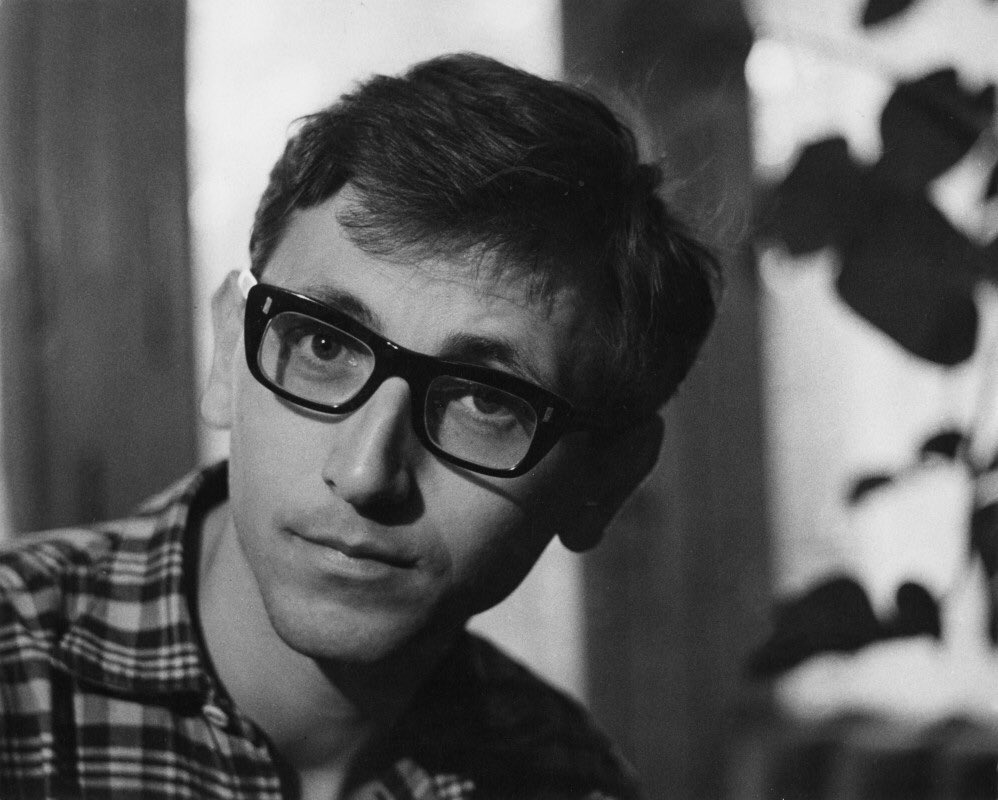

Ivan Passer

"I don't like ambitious films that end in a compromise. I like those little films which are as if by accident important. Those which you suspect of being more important than they at first glance appear to be."

Ivan Passer

|

Ivan Passer, born on December 18, 1933, in Prague, was a notable director, screenwriter, and producer. His work reflected a unique blend of humour, surrealism, and social commentary, distinguishing him within the movement. Passer's films often explore the complexities of human relationships, individualism, and the absurdity of life under an authoritarian regime.

Passer's early life was shaped by the sociopolitical climate of Czechoslovakia. He studied at FAMU, where he developed his passion for filmmaking and storytelling. During his studies, he was influenced by the avant-garde movements of the time and the principles of realism, which would later inform his cinematic style. After leaving film school, Passer collaborated with Miloš Forman, cowriting the screenplays for Loves of a Blond and The Fireman's Ball while also making his directorial debut with Intimate Lighting.

Intimate Lighting (1965)

Ivan Passer's Intimate Lighting (Intimní osvětlení, 1965), is a semi-autobiographical film that captures the quiet lives of rural Czechs during a gathering of musicians. The film is centred on a music teacher named Karel, who returns to his hometown to participate in a small concert. Passer expertly portrays the characters' interactions, using the rustic landscape's backdrop to evoke nostalgia and introspection.

Intimate Lighting is characterized by its gentle humour, warm humanism, and an appreciation for the everyday lives of ordinary people. The film's relaxed pace and focus on character relationships reflect Passer's belief in the importance of personal connections, making it a poignant exploration of the complexities of friendship and creativity. While initially overlooked, Intimate Lighting later gained recognition as a significant film of the Czech New Wave, establishing Passer as a vital filmmaker in the movement.

Jaromil Jireš

"The damage done to a person cannot be repaired like a broken pavement, because human hearts have their own memory."

Jaromil Jireš

|

Born on December 10, 1935, in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, Jaromil Jireš emerged as a central figure in this creative revolution, known for his unique blending of reality and surrealism, as well as his exploration of deeply personal, psychological, and political themes. Jireš's films often grappled with questions of memory, identity, and the absurdities of life under an authoritarian regime, making him one of the most intellectually provocative directors of his time.

Jireš grew up in post-World War II Czechoslovakia, a time of social and political upheaval. He showed an early interest in the arts and eventually pursued filmmaking, attending FAMU. During his time at film school, Jireš was influenced by cinematic movements such as Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave. However, Jireš, like his peers, sought to create a distinctly Czechoslovak style, marked by innovative approaches to narrative and a rejection of the formulaic socialist realism that had dominated the nation's cinematic output for years.

The Cry (1963)

Jaromil Jireš made his feature debut with The Cry (Křik, 1963), a film that is often cited as one of the first works of the Czech New Wave. The film, a quiet exploration of a young couple expecting their first child, examines the intimate details of their relationship and the psychological stresses they experience. Jireš employs an experimental narrative structure, blending real-time events with flashbacks and dreams, creating a fluid and subjective view of the characters' internal worlds.

The Cry marked Jireš as a bold and innovative filmmaker, with its striking use of sound and image to reflect the emotional and psychological landscape of its characters. The film's intimate, personal subject matter and its formal experimentation aligned it with the broader trends of the Czech New Wave, as directors moved away from the state-mandated propaganda films and embraced a more humanistic, individual-centred approach. Jireš's debut earned critical acclaim, signalling his arrival as one of the movement's most promising talents.

The Joke [1969]

|

The Joke (1969)

Jireš's most politically significant film of the 1960s, The Joke (Žert, 1969), is an adaptation of Milan Kundera's novel of the same name. The film follows the life of Ludvík Jahn, a man whose life is ruined when he makes a sarcastic joke about the Communist Party and is expelled from university, sentenced to hard labour, and isolated from his friends and family. Years later, Ludvík attempts to exact revenge on the man who betrayed him, but his plans backfire, leading to a deeper reflection on power, cruelty, and the absurdity of totalitarianism.

The Joke is a darkly satirical look at the devastating consequences of political authoritarianism, using the personal story of Ludvík to critique the broader mechanisms of the Czechoslovak communist regime. Jireš captures the Kafkaesque absurdity of life under a repressive system, where trivial actions can have catastrophic repercussions. The film's stark, unflinching portrayal of the cruelty and arbitrariness of political persecution resonated deeply in Czechoslovakia, especially in the wake of the Prague Spring and the subsequent Soviet invasion of 1968.

Given its overt critique of the communist system, The Joke was banned shortly after its release as part of the broader crackdown on Czech filmmakers following the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact invasion. Despite the censorship, The Joke is now regarded as one of the most important films of the Czech New Wave, both for its artistic achievement and its powerful political message.

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970)

Though technically released in 1970, Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (Valerie a týden divů) is one of Jireš's most famous films and exemplifies the more surreal, fantastical side of the Czech New Wave. Based on a novel by Vítězslav Nezval, the film is a phantasmagorical coming-of-age story about a young girl named Valerie, who navigates a dreamlike, Gothic world filled with vampires, priests, magical objects, and sexual awakenings.

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders is often described as a fairy tale for adults, combining elements of horror, fantasy, and eroticism. The film defies conventional narrative structure, instead weaving together a series of surreal episodes that blur the line between reality and fantasy. Visually stunning and filled with symbolic imagery, the film explores themes of adolescence, sexuality, and the loss of innocence, all while maintaining an enigmatic, almost hallucinatory atmosphere.

Although the film was released just after the peak of the Czech New Wave, it remains one of Jireš's most beloved works, celebrated for its visual daring and imaginative storytelling. It has since gained a cult following, with its influence seen in later surrealist and fantasy cinema. At the time of its release, however, Valerie and Her Week of Wonders was largely ignored, as Jireš, like many of his peers, was sidelined by the new political regime following the 1968 Soviet invasion.

Jan Němec

"I am concerned with man's reactions to the drastic situations in which, through no fault of his own, he may find himself."

Jan Němec

|

Jan Němec was one of the most avant-garde and politically daring filmmakers of the Czech New Wave. Born on July 12, 1936, in Prague, Němec became a prominent figure in the 1960s as a director who pushed the boundaries of both form and content in cinema. His work is characterized by surrealism, experimentation, and a fearless critique of authoritarianism, making him one of the most subversive and radical voices in the movement. Throughout the decade, Němec challenged not only the norms of socialist realism, which dominated Eastern European cinema at the time, but also the broader conventions of filmmaking, creating works that remain influential and provocative to this day.

Jan Němec's early life was shaped by the political turmoil of mid-20th-century Europe. He was born during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia and later came of age under the shadow of Stalinist repression. His family experienced the hardships of both regimes, which would leave a lasting impression on his worldview and cinematic work. Němec studied filmmaking at FAMU, where he was part of a generation of filmmakers who would collectively form the Czech New Wave. His early student films displayed a penchant for unconventional narratives, existential themes, and political subtext, qualities that would define his later work.

Diamonds of the Night (1964)

Němec's feature debut, Diamonds of the Night (Démanty noci, 1964), was based on a novella by Czech writer Arnošt Lusti; the film is an intense, harrowing portrayal of two young Jewish boys who escape from a Nazi transport train during World War II and struggle to survive in the wilderness. What sets Diamonds of the Night apart is its near-total lack of dialogue and its immersive, fragmented narrative that shifts between reality, memory, and hallucination. Němec used disjointed editing and dreamlike sequences to explore the psychological trauma of his characters, creating an atmosphere of existential dread and disorientation.

The film's radical style and structure were groundbreaking, as it departed from traditional war films by focusing less on action and more on the internal, subjective experiences of its protagonists. The film's stark, poetic visuals and its exploration of themes such as fear, survival, and the dehumanizing effects of war create a haunting and immersive experience that lingers in the mind long after viewing.

A Report on the Party and the Guests [1966]

|

A Report on the Party and the Guests (1966)

Němec's second major feature, A Report on the Party and the Guests (O slavnosti a hostech, 1966), is perhaps his most overtly political and controversial work. The film is a biting allegory of totalitarianism, set in a seemingly idyllic countryside where a group of bourgeois picnickers is gradually drawn into a surreal and sinister situation. They are accosted by a strange man and his authoritarian cohorts, who subject them to increasingly absurd and coercive demands, culminating in an elaborate "banquet" hosted by a powerful, omnipresent figure. As the characters are pressured to conform and submit, the film becomes a dark commentary on the mechanisms of control, power, and complicity under repressive regimes.

A Report on the Party and the Guests was a clear critique of the totalitarian mindset, with its allegorical structure pointing to the absurdity and arbitrariness of the power dynamics in communist Czechoslovakia. The film's minimalist style, surrealism, and Kafkaesque atmosphere heightened its impact as a critique of social control. However, its political message did not go unnoticed by the authorities. The film was banned in Czechoslovakia soon after its release, and Němec became a target of state censorship. Nevertheless, the film gained international recognition, earning acclaim at film festivals and becoming an enduring symbol of artistic resistance to oppression.

Martyrs of Love (1967)

After the sharp political critique of A Report on the Party and the Guests, Němec took a different approach with Martyrs of Love (Mučedníci lásky, 1967). The film is a surreal, episodic narrative that follows three separate stories, each centred on a character's search for love and meaning in a chaotic, indifferent world. The film eschews linear storytelling, instead embracing absurdity, visual experimentation, and dreamlike sequences. Martyrs of Love has often been compared to the work of surrealist filmmakers such as Luis Buñuel for its whimsical, sometimes nonsensical scenes that blur the line between reality and fantasy.

Though less politically charged than A Report on the Party and the Guests, Martyrs of Love is a continuation of Němec's exploration of existential themes, such as isolation, longing, and the elusive nature of happiness. The film did not achieve the same level of attention as his earlier works. Still, it further solidified Němec's reputation as an avant-garde filmmaker who refused to conform to conventional cinematic storytelling.

Jiří Menzel

"A person becomes most human, often against his own will, when he begins to founder, when he is derailed and deprived of order".

Jiří Menzel

|

Jiří Menzel was one of the leading figures of the Czech New Wave, a filmmaker whose work blended a profound humanism, wit, and subtle political critique. Born on February 23, 1938, in Prague, Menzel grew up in a culturally rich environment. At FAMU, he studied under legendary Czech filmmakers such as Otakar Vávra and absorbed the new trends in world cinema, including Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave. These influences would shape Menzel's humanistic, observational approach to filmmaking.

Upon graduation, Menzel joined the wave of young directors who sought to subvert the traditional boundaries of Czechoslovak cinema by focusing on ordinary people and their lives, often tinged with absurdity and humor. His early career was closely associated with the works of writer Bohumil Hrabal, whose stories Menzel adapted into some of his most significant works. His films, especially those made during the 1960s, are seen as classics of the Czech New Wave and have left a lasting impact on world cinema.

Closely Watched Trains (1966)

Menzel's breakout film, Closely Watched Trains (Ostře sledované vlaky, 1966), is one of the best-known films of the Czech New Wave and a key work of 1960s European cinema. Based on a novel by Bohumil Hrabal, the film is set during World War II in a small railway station in German-occupied Czechoslovakia. It follows the coming-of-age story of Miloš Hrma, a young and inexperienced railway apprentice who is preoccupied with his sexual insecurities while being oblivious to the broader wartime events around him. As he navigates his personal struggles, he becomes unwittingly involved in a resistance effort against the Nazis.

Closely Watched Trains masterfully combines elements of comedy, pathos, and tragedy, a trademark of Menzel's style. It reflects Menzel's ability to focus on the absurdity of everyday life while simultaneously addressing larger, more profound historical and political themes. The film's light, almost playful tone contrasts with the gravity of the war, creating a layered narrative that reflects both the personal and the political. Closely Watched Trains was a massive success internationally and won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1968, establishing Menzel as a major figure in world cinema.

Capricious Summer [1968]

|

Capricious Summer (1968)

Following the success of Closely Watched Trains, Menzel directed Capricious Summer (Rozmarné léto, 1968), another adaptation of a literary work, this time based on a novel by Vladislav Vančura. The film is a gentle, humorous exploration of the lives of three ageing men who spend their summer days in a small town by a river, engaging in philosophical conversations and contemplating the passing of time. Their monotonous existence is interrupted by the arrival of a travelling circus performer and his beautiful assistant, leading to a series of comical yet melancholic episodes as the men grapple with their fading youth and unfulfilled desires.

Capricious Summer showcases Menzel's ability to create richly detailed, character-driven stories set against the backdrop of seemingly inconsequential events. Like Closely Watched Trains, the film blends humour with a sense of melancholy, exploring themes of ageing, nostalgia, and the passage of time. While not as internationally renowned as Closely Watched Trains, Capricious Summer was well-received for its witty dialogue, gentle humour, and its reflection on human nature.

Larks on a String (1969)

Menzel's next major work, Larks on a String (Skřivánci na niti, 1969), was a much more overtly political film. Another collaboration with writer Bohumil Hrabal, the film was a biting satire of the communist regime and its absurdities, set in a scrapyard where political prisoners and "enemies of the state" are forced to work. The characters, from intellectuals to dissidents, form a diverse group whose lives under repression are depicted with dark humour and irony. The film directly critiqued the communist regime's treatment of individuals and its bureaucratic absurdity, making it one of the more politically charged films of the Czech New Wave.

Because of its political content, Larks on a String was immediately banned by the Czechoslovak authorities following the 1968 Soviet invasion, which brought an end to the relative freedom of expression that characterized the early years of the Czech New Wave. The film remained suppressed for over 20 years and was only officially released in 1990, after the fall of communism. Despite its initial censorship, Larks on a String won the Golden Bear at the 1990 Berlin Film Festival upon its eventual release, and it is now regarded as one of Menzel's finest works.

A selection of other important films associated with the Czechoslovak New Wave

The Sun in a Net (1963)

The Sun in a Net (Slnko v sieti, 1963), directed by Štefan Uher, is a visually striking and introspective drama that explores themes of love, isolation, and societal change. The film follows the emotional turmoil of two young lovers, Fajolo and Bela, whose relationship is tested by distance and personal disillusionment. Through poetic imagery, nonlinear storytelling, and innovative cinematography, the film captures the complexities of human connection and the quiet frustrations of everyday life. The contrast between urban and rural settings reflects deeper social tensions, while the use of light and shadow enhances the film’s meditative tone. With its subtle critique of conformity and its focus on personal emotions, the film stands as a landmark in Czechoslovak cinematic history, foreshadowing the style and themes that would define the emerging New Wave.

The Cassandra Cat [1963]

|

The Cassandra Cat (1963)

Directed by Vojtěch Jasný, The Cassandra Cat (Až přijde kocour, 1963) is a whimsical yet subversive fantasy film that blends magical realism with biting social commentary. The film is set in a small town where a mysterious traveling circus arrives, accompanied by a cat that, when it removes its sunglasses, reveals the true nature of the townspeople by changing their colors. Those who are deceitful or hypocritical are marked in shades of red, blue, or yellow, depending on their flaws. While at first glance, The Cassandra Cat may appear to be a light-hearted fairy tale, it is in fact a sharp critique of the social conformity and hidden vices in Communist society. Its bright colors, imaginative storytelling, and allegorical nature make it an underrated gem of the New Wave, balancing charm with subversive political insight.

Lemonade Joe (1964)

Lemonade Joe (Limonádový Joe aneb Koňská opera, 1964), directed by Oldřich Lipský, is a surreal and satirical Czechoslovak Western that parodies the classic tropes of American Western films while blending absurd humour with political commentary. Set in the Old West, the film tells the story of Lemonade Joe, a sharp-shooting, teetotaling cowboy who promotes Kolaloka, a non-alcoholic lemonade, as a healthier alternative to whiskey, thereby bringing order to the lawless town. The film's vibrant use of colour, slapstick comedy, and exaggerated characters give it a cartoonish quality, while its absurd plot serves as a critique of both capitalist advertising culture and Western genre clichés. As a product of the Czechoslovak New Wave, Lemonade Joe is known for its inventive visual style and subversion of mainstream cinematic conventions, all while maintaining a light-hearted, comedic tone. It remains a cult favourite for its unique blend of satire, musical numbers, and genre parody.

The Shop on Main Street [1965]

|

The Shop on Main Street (1965)

The Shop on Main Street (Obchod na korze, 1965), directed by Ján Kadár and Elmar Klos, is a powerful and poignant Czechoslovak drama set during World War II in Nazi-occupied Slovakia. The film tells the story of Tóno Brtko, a simple, morally conflicted carpenter who is appointed by the fascist government to take over a small shop owned by an elderly Jewish widow, Mrs. Lautmannová, as part of the Aryanization of Jewish businesses. Unaware of the larger political context and her impending fate, Mrs. Lautmannová believes Tóno is her new helper, not realizing the gravity of the situation. As Tóno becomes entangled in the moral dilemma of protecting the old woman or complying with the Nazi regime, the film explores themes of guilt, complicity, and the devastating human cost of oppression. The Shop on Main Street won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1966.

Pearls of the Deep (1966)

Pearls of the Deep (Perličky na dně, 1966), is a landmark anthology film of the Czechoslovak New Wave, directed by five emerging filmmakers—Jiří Menzel, Jan Němec, Evald Schorm, Věra Chytilová, and Jaromil Jireš. Based on short stories by renowned Czech author Bohumil Hrabal, the film consists of five vignettes that explore the lives of ordinary people in postwar Czechoslovakia, blending absurdist humour with surreal and poignant moments. Each segment reflects the distinctive style of its director, but together they present a common thread examining the quirks, dreams, and disappointments of everyday life, often with a subtle critique of social conformity. Pearls of the Deep is celebrated for its innovative storytelling, its lyrical cinematography, and its reflection of the New Wave's emphasis on individualism, spontaneity, and the exploration of human eccentricities.

Marketa Lazarová [1967]

|

Marketa Lazarová (1967)

Marketa Lazarová (1967), directed by František Vláčil, is an epic medieval drama that immerses viewers in a brutal yet poetic vision of the past. Adapted from Vladislav Vančura’s novel, the film tells the story of a young woman, Marketa, who becomes entangled in the violent conflicts between warring clans and the encroaching forces of Christianity. With its striking black-and-white cinematography, fragmented narrative, and dreamlike atmosphere, the film eschews traditional storytelling in favor of a more immersive, almost hallucinatory experience. Its raw depiction of medieval life—filled with bloodshed, faith, and destiny—creates a haunting and visceral portrait of an era where survival and morality often collide. Widely regarded as one of the greatest historical films ever made, Marketa Lazarová is a monumental cinema achievement.

The Cremator (1969)

The Cremator (Spalovač mrtvol, 1969), directed by Juraj Herz, is a haunting and surreal masterpiece of the Czechoslovak New Wave that combines elements of horror, dark comedy, and political satire. The film follows Karel Kopfrkingl, a meticulously mannered crematorium worker in 1930s Prague, whose obsession with death and the liberation of souls through cremation becomes intertwined with the rising tide of Nazi ideology. As he becomes increasingly delusional, Kopfrkingl is manipulated into committing horrifying acts under the guise of duty and purification. The film is renowned for its striking black-and-white cinematography, innovative camera work, and a chilling performance by Rudolf Hrušínský as Kopfrkingl. The Cremator offers a profound critique of totalitarianism. It explores how ordinary individuals can become agents of evil, making it a powerful and unsettling commentary on conformity, manipulation, and the corrupting influence of ideology.

Birds, Orphans and Fools [1969]

|

Birds, Orphans and Fools (1969)

Birds, Orphans and Fools (Vtáčkovia, siroty a blázni, 1969), directed by Juraj Jakubisko, is a visually striking and surreal film that reflects the anarchic spirit of the Czechoslovak New Wave, offering a poignant and tragicomic exploration of freedom, love, and the absurdity of life under oppression. Set in a bleak, postwar world, the film follows three carefree and eccentric characters—a man, a woman, and an orphan—who live together in an unconventional ménage à trois, trying to escape the horrors of reality through a life of playfulness and fantasy. Their seemingly innocent and absurd existence, however, is overshadowed by the looming presence of political repression and societal collapse. Known for its chaotic, dreamlike imagery and avant-garde style, Birds, Orphans and Fools uses surrealism and allegory to critique the loss of individual freedom under authoritarian regimes, capturing the disillusionment and despair of the 1960s in Eastern Europe. The film was banned shortly after its release due to its subversive themes but has since gained recognition as a significant work of the Czechoslovak New Wave.

Case for a Rookie Hangman (1970)

Case for a Rookie Hangman (Případ pro začínajícího kata, 1970), directed by Pavel Juráček, is a surreal and allegorical adaptation of Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, reimagined as a bold critique of bureaucracy and authoritarianism within a totalitarian regime. The film follows Lemuel Gulliver as he stumbles into the strange, dystopian land of Balnibarbi, where absurd laws, rigid systems, and nonsensical customs rule. Blending Kafkaesque themes of alienation with dark, satirical humour, the film presents a nightmarish vision of a world where individual freedom is crushed by oppressive societal forces. Through its avant-garde style, dreamlike narrative, and pointed commentary on political repression, Case for a Rookie Hangman resonates as a reflection on life in Czechoslovakia during the Soviet occupation. Banned soon after its release, the film remains a vital work of the Czechoslovak New Wave, known for its daring critique of conformity and its exploration of the absurdity of power.

The Ear [1970]

|

The Ear (1970)

The Ear (Ucho, 1970), directed by Karel Kachyna, is a critical reflection on the paranoia of life under a totalitarian regime. The film follows a couple, a government official and his wife, as they host a dinner party that takes a disturbing turn when they discover a hidden microphone in their home. This discovery spirals into a tense exploration of trust, betrayal, and the oppressive nature of the state. The Ear is marked by its claustrophobic atmosphere and psychological intensity, showcasing Karel Kachnyna's ability to blend dark humor with a chilling critique of the totalitarian regime. The film's use of sound and visual metaphor emphasizes the pervasive surveillance and lack of privacy experienced in a repressive society. Despite its innovative storytelling and thematic depth, The Ear faced censorship due to its political implications, and it was banned shortly after its release. However, it later gained acclaim for its daring portrayal of life under an oppressive system and is considered one of the essential works of the Czech New Wave.

The End of the Czechoslovak New Wave

The end of the Prague Spring

|

The Czechoslovak New Wave flourished during a period of relative political freedom and intellectual openness in the 1960s. However, this brief period of freedom came to an end in 1968 with the Prague Spring, a movement led by reformist Communist leader Alexander Dubček, who attempted to create "socialism with a human face." His policies sought to liberalize the country's political and economic systems, allowing for greater freedom of expression and dissent. During this time, artists and intellectuals were emboldened, and the film industry thrived with its critiques of authoritarianism, censorship, and conformity.

The optimism of the Prague Spring was brutally crushed in August 1968 when Soviet and Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia, putting an end to Dubček's reforms. The invasion marked the beginning of a period known as "normalization," a reassertion of hardline Communist control over the country. This had immediate and devastating consequences for the Czechoslovak New Wave.

Censorship and Repression

After the invasion, the government began to reassert strict control over the arts, implementing censorship and suppressing any work deemed critical of the regime. Filmmakers who had previously enjoyed relative freedom were now subject to heavy scrutiny. Many films that had been produced during the height of the New Wave were banned, often for decades, and those who had made them were either blacklisted or forced into exile.

Some filmmakers, such as Miloš Forman and Ivan Passer, left the country and found success abroad, particularly in Hollywood. Others, like Věra Chytilová and Jiří Menzel, stayed in Czechoslovakia but faced significant difficulties in continuing their careers. Chytilová, for example, was banned from filmmaking for several years, while Menzel struggled to get projects approved under the repressive regime.

Filmmakers who remained in Czechoslovakia were either forced to conform to the ideological demands of the state or found themselves working on projects with little political relevance, often far removed from the bold and innovative work that had characterized the New Wave.

The Banning of Films

One of the most direct consequences of the crackdown was the banning of several key films. Films like The Firemen's Ball (1967) by Miloš Forman, The Joke (1969) by Jaromil Jireš, and Larks on a String (1969) by Jiří Menzel were shelved for years, as they were seen as critical of the Communist regime and too subversive for public release. Larks on a String, for example, was banned for over 20 years and wasn't shown publicly until 1990, after the fall of Communism. The film, a biting satire on the absurdities of the socialist system, was seen as too dangerous during the era of normalization. Similarly, The Joke, based on a novel by Milan Kundera, critiqued the Stalinist purges and the cruelty of political retribution, making it a target for censorship. These films, which had once represented the cutting edge of Czechoslovak cinema, were now hidden away, only to be rediscovered after the Velvet Revolution in 1989, when the Communist regime finally fell.

The Aftermath: Exile, Compromise, and Legacy

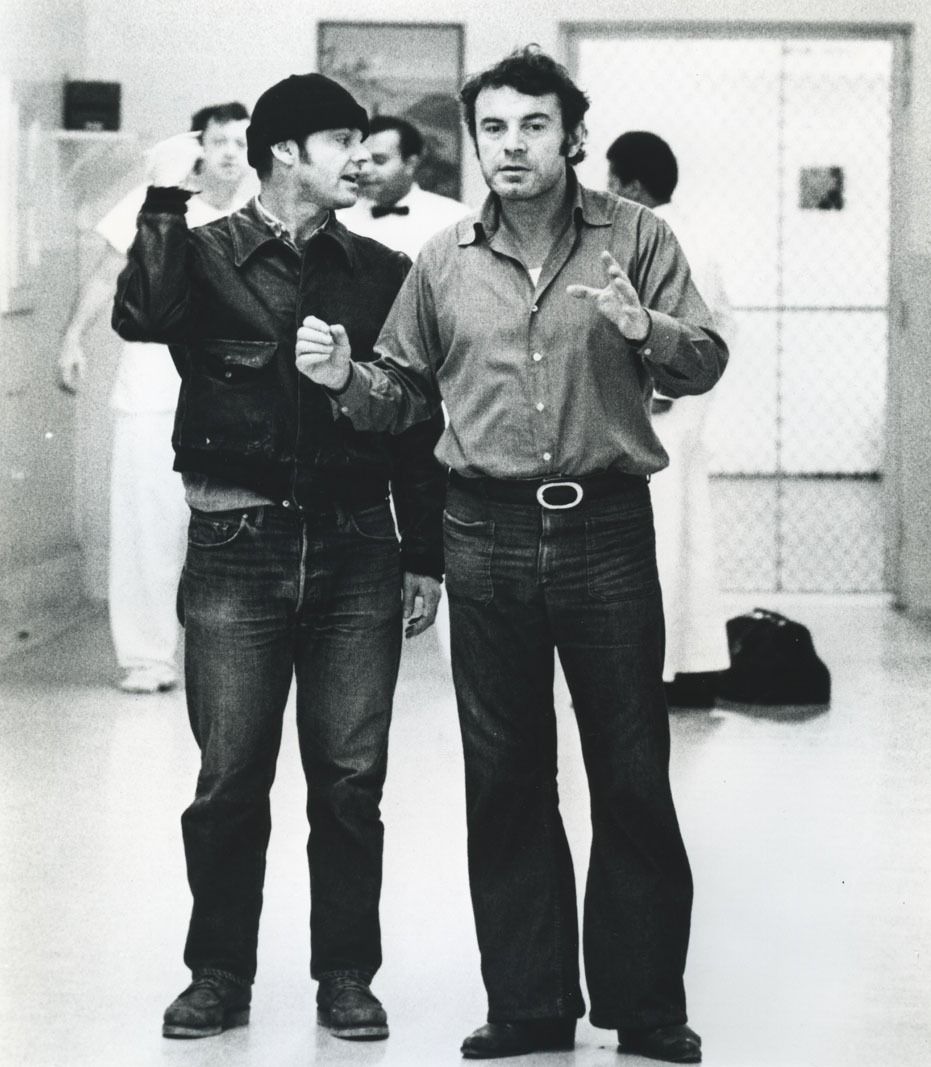

Milos Forman on the set of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

|

Filmmakers in Exile

For some directors, the political climate in Czechoslovakia became untenable, leading them to seek creative freedom abroad. Miloš Forman, perhaps the most prominent figure to emerge from the New Wave, left Czechoslovakia for the United States after the invasion. There, he went on to have an illustrious career, directing iconic films such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975) and Amadeus (1984), both of which won Academy Awards. Forman's success in Hollywood exemplified the artistic resilience of New Wave filmmakers, but it also underscored the cultural loss for Czechoslovakia, which was deprived of some of its most talented artists. Ivan Passer also moved to the United States, where he became a respected independent filmmaker, although he never achieved the same level of recognition as Forman.

Filmmakers Who Stayed

For directors who remained in Czechoslovakia, life became far more difficult. Věra Chytilová, known for her anarchic and feminist film Daisies (1966), was effectively blacklisted for several years. Despite this, she refused to leave the country or compromise her artistic vision. After a period of inactivity, she eventually returned to filmmaking, though her later works were subject to intense scrutiny by the censors. Chytilová remained defiant throughout her career, continuing to critique the regime subtly even in her later films.

Jiří Menzel, another prominent figure of the New Wave, also faced restrictions. His film Larks on a String, which had been banned in 1969, wasn't released until after the fall of Communism in 1990. During the normalization period, Menzel was allowed to work, but the content of his films was often sanitized and apolitical, far from the daring work of his earlier career.

Larks on a String (1969)

|

The Rediscovery of Suppressed Films

With the Velvet Revolution of 1989 and the subsequent collapse of the Communist regime, many of the banned and suppressed films of the Czechoslovak New Wave were rediscovered and reappraised. Films like Larks on a String, The Joke, and The Cremator were finally released to the public, revealing the depth and brilliance of a movement that had been prematurely curtailed.

These films, which had been hidden for decades, began to circulate in international film festivals and retrospectives, allowing a new generation of viewers to appreciate their artistry and their political significance. The late release of these works also provided insight into the experiences of artists working under totalitarianism and the personal costs of political repression.

Legacy of the Czechoslovak New Wave

Despite its abrupt end, the Czechoslovak New Wave left a profound and lasting legacy on world cinema. Filmmakers such as Forman, Menzel, and Chytilová not only made significant contributions to the global film canon but also influenced future generations of filmmakers with their blend of surrealism, dark humor, and political critique. The movement's themes—individualism, resistance to authoritarianism, and the absurdity of life under a repressive system—remain relevant today. The New Wave's fearless experimentation with narrative structure, its blending of realism and fantasy, and its sharp social commentary continue to inspire filmmakers worldwide. Moreover, the rediscovery of the movement's films in the 1990s and beyond has allowed them to be appreciated not only as historical documents of a tumultuous political era but also as timeless works of art that resonate across cultures and generations.

Return to: 'International New Wave'.

|