|

Michael Brooke, Curator |

To celebrate the British Film Institute’s major retrospective of the work of Jerzy Skolimowski, newwavefilm.com interviewed the season’s curator Michael Brooke about the director’s remarkable career. The BFI's Outsiders and Exiles: The Films of Jerzy Skolimowski offers a rare opportunity to see the work of a filmmaker once dubbed a one man Polish New Wave, whose career has spanned more than six decades.

The season takes place at BFI Southbank from 27 March to 29 April, and is presented in partnership with the Kinoteka Polish Film Festival, which is organised by the Polish Cultural Institute and supported by the Polish Film Institute.

We have partnered with the BFI to offer 2 for 1 tickets using the code 241JERZY at the BFI website.

As the curator of this month-long Jerzy Skolimowski retrospective at the BFI, can you give a brief overview of what it will include and some highlights of the season?

Jerzy Skolimowski Jerzy Skolimowski |

It’s not complete, but it includes the vast majority of the films that Skolimowski directed between his debut in 1964 and his most recent film EO, which premiered at Cannes less than a year ago. Since this is a joint project between the BFI and the Kinoteka Polish Film Festival, I was particularly keen to focus on his Polish output, which falls into two distinct phases (1964-67 and 2008-22). That’s a complete survey, but we’ve also included his ‘French New Wave’ (albeit Belgian-made) film Le Départ (1967) and five films from his mid-career period in exile, one of which is a very rare (possibly even British premiere) screening of Dialogue 20-40-60 (1968), an experimental portmanteau feature that he made in Czechoslovakia with Zbyněk Brynych and Peter Solan, the experimental bit being that all three filmmakers were shooting the same dialogue exchange, but with actors from successively different generations (Skolimowski tackles the couple in their twenties, the male half of which is Jean-Pierre Léaud as a Slovak rock star).

Why have you titled the retrospective Outsiders and Exiles?

There was a lot of brainstorming about this, not least because I’m mindful of the fact that Ewa Mazierska’s book Jerzy Skolimowski: The Cinema of a Nonconformist (2010) takes issue at quite an early stage with the notion of Skolimowski being an outsider as an artist – she points out, reasonably, that most of his films have been made squarely within the bounds of the national film industry of whatever country they’re made in, that he’s worked with major stars, for the most part they’re very narratively accessible, and so on.

All of which is true, but it nonetheless seemed to me that if there’s a truly consistent theme running through all of Skolimowski’s films it’s that of someone alienated from the world around him (Skolimowski’s protagonists are invariably male; in fact, female leads are often played by his then partner/wife), sometimes because he’s suddenly been plunged into an unfamiliar environment (Deep End, Moonlighting, Essential Killing, EO) or at others because despite growing up in that environment he finds himself increasingly removed from it (Identification Marks None, Walkover, Barrier, Four Nights with Anna). And of course Skolimowski was himself an exile from his native Poland between the late 1960s and the early 2000s – although, unlike compatriots like Walerian Borowczyk, Roman Polanski or Andrzej Żuławski, he eventually came back, and his four most recent films (Four Nights with Anna, Essential Killing, 11 Minutes, EO) were all primarily Polish productions.

Skolimowski seems to have been very determined to make a mark in the world from an early age. Before he became a director, he was a semi-professional boxer and a published poet, and he made his first feature film while he was still at film school – something unheard of at the time. Are there aspects of Skolimowski’s dynamic personality that you see echoed in his films? What makes a film a Skolimowski film?

Although his films have varied hugely in style over the decades – on the surface, there’s very little that, say, the explosively inventive Barrier (1966) has in common with the quiet, contemplative Moonlighting (1982) – the vast majority revolve to at least some extent around a protagonist simultaneously trying to ‘fit in’ while being acutely conscious that circumstances over which they often have no control make this impossible. Sometimes this is in the form of garrulous social satire (the early Polish films), sometimes in near-silence - Vincent Gallo’s Mohammed in Essential Killing (2010) says almost as little as EO the donkey (arguably less, as EO can get quite vocal at times) – but they’re all recognisably the same character at base.

Dynamically, the films are consistently inventive and often in delightfully unexpected ways – the lengthy, virtuosic takes in the first two films (1965’s Walkover has just 29 shots in total), the splashes of strong primary colours in 1970’s Deep End (his first colour film over which he had full artistic control), the avant-garde composer played by John Hurt trying to find new sounds in The Shout (1978) by trapping a wasp in a jar, the notion of shoplifting as a game as well as a means of survival in Moonlighting (a concept inspired by Bresson’s Pickpocket), the fractured narrative of 11 Minutes (2015), whose temporal span is indeed eleven minutes but we see it from so many different and overlapping perspectives that it’s stretched out to seven times that – right from his very first shorts (1960-61) through to EO, Skolimowski’s approach has always been restless, questing, constantly trying out new ideas, but always allied to a notably strong and consistent artistic personality.

Identification Marks None (1964) Identification Marks None (1964) |

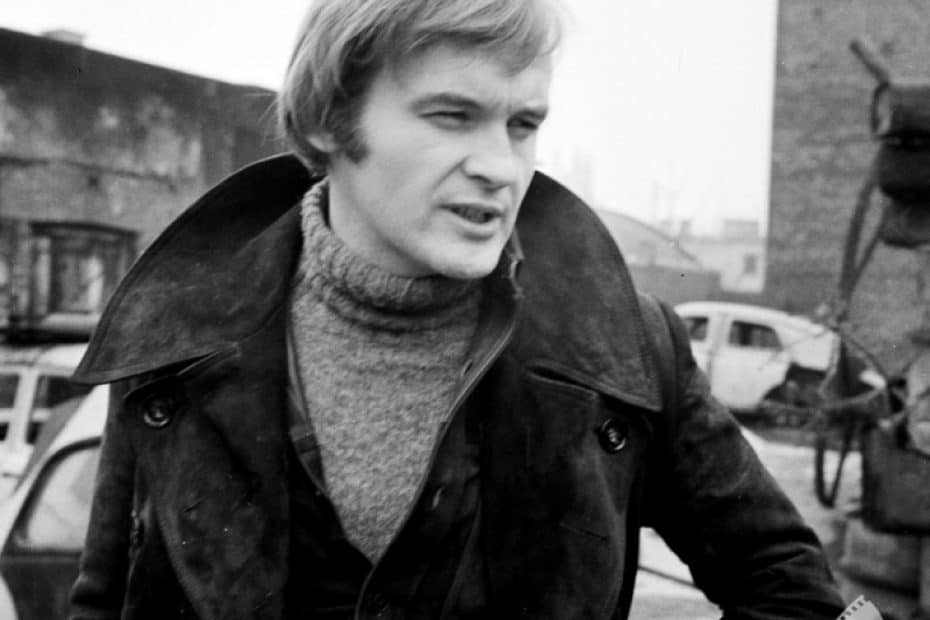

And this may seem like a comparatively trivial point, but despite the richness of their content a Skolimowski film is far more likely to be under than over 90 minutes, and on several occasions that first digit is just 7. Which also suggests a filmmaker who knows exactly what he wants to achieve, and how to express it as efficiently as possible. Talking of which, you allude to a story that’s been told a gazillion times already, but it always bears repeating – when at the Łódź Film School, Skolimowski initially made short-film exercises in the usual way (four of them are being shown in the retrospective, supporting Dialogue 20-40-60), but then hit upon the inspired and, as far as I can see, unprecedented idea of planning future film-school exercises so that they’d cut together coherently to make a feature, and that became Identification Marks None (1964). He played the lead not out of egomania but because he wanted an actor on whom he could totally rely – similarly, his girlfriend at the time, Elżbieta Czyzewska, played multiple female roles.

Between 1964 and 1967 Skolimowski made four semi-autobiographical feature films in Poland: Identification Marks: None, Walkover, Barrier, and Hands Up! These are the films that established his reputation. They were visually striking, experimental and political. Hands Up! in particular caused a stir and landed him in hot water with the Polish government. These films, until recently, have not been easily accessible. For the uninitiated, can you talk a bit about them, why they were so radical at the time and the impact they had both culturally and aesthetically?

I’m loath to say that these were the first Polish films ever to feature a writer-director-star, as that’s the kind of sweeping statement that someone will be itching to disprove – but I’ve yet to turn up an earlier example. So that aspect alone made them strikingly different not just from any previous Polish film but also from the vast majority of ‘new wave’ films being made elsewhere: the auteur was also the onscreen protagonist. (He was prevented from starring in Barrier, as he originally intended, but at one point contrives to have Jan Nowicki wrapping a poster of Skolimowski’s own face around his head, in a “director’s cameo” that’s every bit as witty, not to say downright cheeky, as Hitchcock’s “before” and “after” slimming ad in a newspaper in Lifeboat a couple of decades earlier.)

And there hadn’t really been a character in Polish cinema quite like his Andrzej Leszczyc either (the protagonist of Identification Marks: None, Walkover and Hands Up!) – there might have been hints in, say, Zbigniew Cybulski’s conflicted assassin in Ashes and Diamonds or Tadeusz Janczar’s similarly troubled Stach in Wajda’s debut A Generation (1955), but Leszczyc has far more in common with Western antiheroes like James Dean’s Jim Stark, Jean-Paul Belmondo’s Michel Poiccard, or literary models like J.D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield, in that they all embody a particular existential crisis that wasn’t at all uncommon amongst the younger generation across the board. Skolimowski has stressed that Andrzej Leszczyc is a fictional character and not a literal alter ego, but they nonetheless have much in common besides looking identical – in particular, Leszczyc’s evident uncertainty about how he wants his life to proceed matches Skolimowski’s own a few years earlier. He said that working as a lighting director for Krzysztof Komeda’s performances would have been a great job under normal circumstances, in terms of good pay for minimal effort, and that many would gladly have turned it into a full-time career, but he felt that he needed to do something more personally fulfilling without being entirely sure quite what (at least at first) – although he didn’t do what Leszczyc does in the first film, and join the army in the hope that it will give his life some focus. (It doesn’t, as the quasi-sequel Walkover goes on to demonstrate!)

Barrier has much in common with the two earlier films, albeit with the alienated protagonist this time played by a professional actor (Jan Nowicki) and a notably more fractured and overtly experimental approach, to such an extent linguistically that it’s claimed that you really have to be Polish to understand all the script’s many nuances, something that I’m not in a position to confirm or deny (but I have no reason to disbelieve it). But even if it’s hard to grasp at a first or even subsequent viewing, it’s a thrilling example of a filmmaker properly spreading his creative wings, with individual set-pieces as visually memorable as anything else being made that decade – notably the idea that inspired the film in the first place, of a man descending a ski jump on a suitcase.

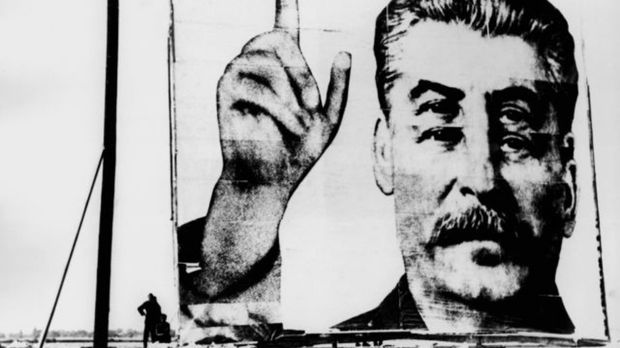

Hands Up! (1967) Hands Up! (1967) |

Politics had obliquely been referred to in the earlier films, but came to the fore in Hands Up! (1967), where Skolimowski seems to have gambled that because he was an increasingly renowned name in the West, the Polish authorities would be reluctant to criticise him – and this gambit has worked for other eastern European filmmakers: Wajda in particular was a master at this (as ruefully acknowledged by his former assistant Andrzej Żuławski, who admitted that he lacked Wajda’s diplomatic skills). But Hands Up! was considered much too near the knuckle, not so much for its satirical portrait of Stalin (whose gigantic poster with inadvertently duplicated eyes is one of the most memorable images in Skolimowski’s entire output) but for its more or less overt acknowledgement that there was an entire generation of Poles that felt alienated from Polish society, and that government policy over the last decade was a substantial part of the reason. The film was scheduled to play in competition at the Venice Film Festival, but was abruptly cancelled a few days in advance, and when Skolimowski made a personal plea to Zenon Kliszko, the country’s de facto number two, he might as well have been addressing a brick wall. Finally, in frustration, Skolimowski said that if Hands Up! wasn’t screened he’d never make another film in Poland again, and… well, that’s why he went into exile.

Skolimowski was part of a new creative generation in the 1960s in Poland that included his friends Roman Polanski and the jazz musician Krzysztof Komeda. Some have compared what was happening in Poland at that time to the new waves in France, Czechoslovakia, and elsewhere. Would you say there was a Polish New Wave film movement that Skolimowski played a part in?

You’re absolutely right about the emergence of a new creative generation, but it actually started to emerge in the mid-1950s, and when the Stalinist cultural policies that had held sway from 1949-56 were formally abolished by the incoming Władysław Gomułka administration in October 1956, this directly triggered a creative explosion across multiple media: cinema, theatre, literature, music (especially jazz and experimental music), painting, sculpture, you name it. Some huge names in Polish culture first made a splash during this period – Polanski and Komeda, as you rightly say, but also Andrzej Wajda, Andrzej Munk and Jerzy Kawalerowicz in cinema, Jerzy Grotowski in theatre, Krzysztof Penderecki in experimental music, Walerian Borowczyk and Jan Lenica in animation, and so on. And Skolimowski’s first creative output was published at about the same time, but in the form of poetry rather than anything to do with cinema (in which he’d shown no significant interest prior to the late 1950s).

Andrzej Wajda Andrzej Wajda |

But the question of whether Skolimowski himself was part of that movement is somewhat more complicated, because by the mid-1960s pretty much nobody else was making films even remotely like his in Poland, and they didn’t have that much in common with Polish films from 1957-62 either, which were collectively referred to as ‘the Polish Film School’ – the notion of a ‘new wave’ hadn’t taken root then, as this predated the French and British versions. And the Polish Film School generation all had teenage, sometimes adult and usually first-hand experiences of active service in WWII (if only as a teenage messenger for the Polish Home Army in Wajda’s case), a factor that can’t be discounted either: Skolimowski himself was only seven when it ended.

Also, and I think this is significant with regard to Skolimowski, only one of the feature films from this period was in any way experimental – Tadeusz Konwicki’s The Last Day of Summer (1958), which was still pretty restrained compared with what Jean-Luc Godard and Věra Chytilová would come up with not long afterwards. It’s short films, documentaries and animation, including Polanski’s Two Men and a Wardrobe and Borowczyk and Lenica’s Dom (1958) that leaned more in that direction. None of which is to minimise the importance of, say, Wajda’s Kanal (1957) and Ashes and Diamonds (1958), Munk’s Eroica (1957) and Bad Luck (1960) or Kawalerowicz’s Night Train (1959) or Mother Joan of the Angels (1961) – they’re great films by any sensible yardstick, but just not on the cutting edge of film form, and nor did their makers intend them to be.

But it’s thanks to Wajda that Skolimowski got his first professional leg-up – the story goes that the two men were coincidentally staying at the same writers’ retreat organised by the Polish Writers’ Union in 1959. At that time, Skolimowski was a published poet with aspirations as a playwright while Wajda, twelve years older, was wrestling with the script of his fifth feature Innocent Sorcerers (1960), which was his first with a contemporary setting. He was very conscious of the fact that this script was about young people at the turn of their twenties, but he was already in his mid-thirties and co-writer Jerzy Andrzejewski (the original novelist and subsequent co-screenwriter of Ashes and Diamonds) was pushing fifty – so he buttonholed Skolimowski, as the nearest representative of that generation to hand, and asked him if he could have a look at the script. (Incidentally, I love this 180˚ inversion of the classic “neophyte twentysomething accosts older and more established artist” trope!).

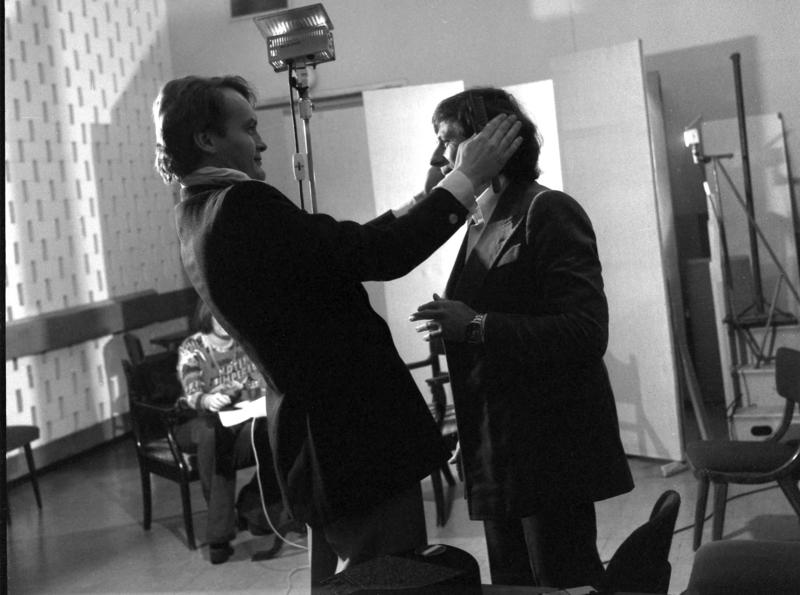

Skolimowski and Polanski Skolimowski and Polanski |

Skolimowski, unsurprisingly, was deeply unimpressed with the script’s portrait of his generation, which he said didn’t ring true at all – in particular, these young people showed no interest in jazz, which was simply not credible to him. So Wajda suggested that he tweak it, and Skolimowski seems to have rewritten it wholesale, for which presumption he not only shared an onscreen credit with Andrzejewski but also played a small part, as a boxer prevented from entering the ring for medical reasons. And when offscreen, Wajda made exactly the same suggestion to Skolimowski that he’d made to a young actor by the name of Roman Polanski back in 1954 – why didn’t he try out for the Łódź Film School, whose entrance exam was then imminent. With no great expectation of passing, Skolimowski sat the exam… and the rest is history.

Another contact he made on the Innocent Sorcerers project was Roman Polanski (who played a supporting role), who similarly asked Skolimowski to take a look at his first feature-length screenplay. There were no issues with unconvincing portrayals of young people in Knife in the Water, of course, but Skolimowski made several important suggestions, one of which was to telescope the action into a single 24-hour period. So well before he graduated from Łódź in 1964, Skolimowski had already made significant creative contributions to the work of two major Polish filmmakers.

French critics praised Skolimowski’s early films and Jean-Luc Godard famously wrote a letter to Skolimowski describing the two of them as the greatest directors in the world. Do you see parallels between Godard’s approach to filmmaking and Skolimowski’s?

Barrier (19 Barrier (1966) |

Very much so, although it appears to be coincidental; Skolimowski said that he hadn’t seen any of Godard’s films at the time when this comparison was initially made, and there’s no reason to disbelieve him. (Skolimowski has never come across as being much of a film buff). But it’s really not hard to discern very strong similarities between the likes of, say, Breathess and Bande à part on the one hand and Identification Marks None and Barrier on the other – they all exhibit the same near-miraculous combination of meticulous technical control and instinctive improvisation, allied with a film sense that seems to emerge from both men’s subconscious more than anything else. Skolimowski’s films have been strongly linked to his love of poetry and jazz, and the same impulses seem to drive much of Godard’s work – and of course both men became increasingly political as the Sixties progressed, in both cases resulting in sharp creative ruptures circa 1967 (with Skolimowski physically exiled from Poland, and Godard doing something very similar with regard to his links with the mainstream French film industry).

Although there are also significant differences: Skolimowski professes to hate analysing his own films, and actively bridles whenever anyone asks him a question along those lines, whereas Godard seemed to revel in it (however delightfully misleading his responses often were). And it’s hard to imagine Skolimowski allying with something like the Dziga Vertov Group, and equally hard to imagine Godard playing villains or mad scientists in mainstream Hollywood films like White Nights (1985), Mars Attacks! (1996) and Avengers Assemble (2012) – Werner Herzog is the only major European auteur who can match that unlikely achievement.

After the controversy surrounding Hands Up! Skolimowski left Poland and became an international director living and working in Britain, America and elsewhere. From this time on his work became more diverse and included literary adaptations. Do you think there are consistent themes that run through these films? Are there any you recommend from this period?

He made several of his best films from this period, and I’m delighted that we managed to secure many of them for the retrospective. Skolimowski himself ranks Deep End, The Shout and Moonlighting very high indeed amongst his output, and quite rightly. I’m also very pleased that we’re able to show The Lightship (1985), his only entirely US-made film and the closest he came to a pure genre piece, although with lead actors of the calibre of Robert Duvall and Klaus Maria Brandauer its other pleasures are immense as well.

Moonlighting (19 Moonlighting (1982) |

As for recurring themes: all three of the British films singled out above revolve around a protagonist who’s “apart” from the rest of the world in some way, whether it’s a shy teenage virgin (John Moulder-Brown) getting his first proper job (and a great deal of often unwanted attention from middle-aged female customers and his slightly older colleague, played by Jane Asher), or a man who’s spent years living in the Australian outback (Alan Bates) to master shamanic skills denied his less curious fellow Britons (one, of course, being a shout whose potency can literally kill those within earshot), and Nowak (Jeremy Irons), the leader of a quartet of Polish builders working illegally in London, who finds out about the December 1981 declaration of martial law back home but resolves to keep it from his colleagues, and then finds himself resorting to shoplifting after his meagre funds run out – so he’s effectively alienated from everything around him. These are themes that are also explored in his later Polish films, Four Nights with Anna (2008), Essential Killing (2010) and of course EO (2022) – species aside, there’s not a lot that separates the latter’s protagonist from the likes of Nowak; they’re both victims of circumstance who end up stranded abroad.

You mention literary adaptations, about which Skolimowski has mixed feelings – he loathes The Adventures of Gerard (1969), a very unhappy experience for him as he simply had no experience of shooting a medium-budget period drama under Western industrial filmmaking conditions, and indeed nearly got fired mid-production (Claudia Cardinale rescued him by saying “if he goes, I go”). He’s also none too keen on his adaptations of Vladimir Nabokov (1972’s King Queen Knave), Ivan Turgenev (1989’s Torrents of Spring) and Witold Gombrowicz (1991’s Ferdydurke), regarding the latter in particular as such a disaster that he took a break from filmmaking for what turned out to be seventeen years. Those films aren’t showing in the retrospective, although not because of any kind of Skolimowski-mandated veto; it was just that they were much harder to track down in terms of rights clearance and showable copies. (Since Ferdydurke has barely been seen anywhere – I’ve only seen it via a pretty terrible-quality Polish DVD - it might have been an interesting addition, although Skolimowski’s right about it being a serious tonal misfire; Gombrowicz has been a near-impossible nut for filmmakers to crack, although Andrzej Żuławski’s 2015 swansong Cosmos made a better fist of it). On the other hand, despite his general antipathy towards adaptations, he not only regards the Robert Graves-sourced The Shout as one of his best films, but hand-picked it to follow the career-retrospective Q&A in London on March 28th.

My only big regret about the retrospective is that we couldn’t get Success is the Best Revenge (1984), a fascinating film maudit that has more in common with his early Polish work than anything else that he made in exile (it’s about the fractious relationship between a Polish theatre director in exile in London and his troubled teenage son; the latter being played by Skolimowski’s own son Michał). But while we tracked down a French-subtitled 35mm print courtesy of co-producers Gaumont, we then drew a blank with the identity of the current UK rightsholder, as Skolimowski himself lost the rights when the film’s financial failure also cost him his house, triggering his move to the US, and he couldn’t help us identify the current rightsholder, which may well be some financial institution or other. So fingers are crossed that Gaumont will do something with it on Blu-ray at some point, as it would be a crying shame if that film was buried and (even more) forgotten – the film’s in English, so there won’t be a language barrier.

Despite his reputation, Skolimowski’s films have often received mixed reviews and have not always fared well at the box office. Do you think there’s something about his distinctive vision that’s incompatible with the commercial mainstream?

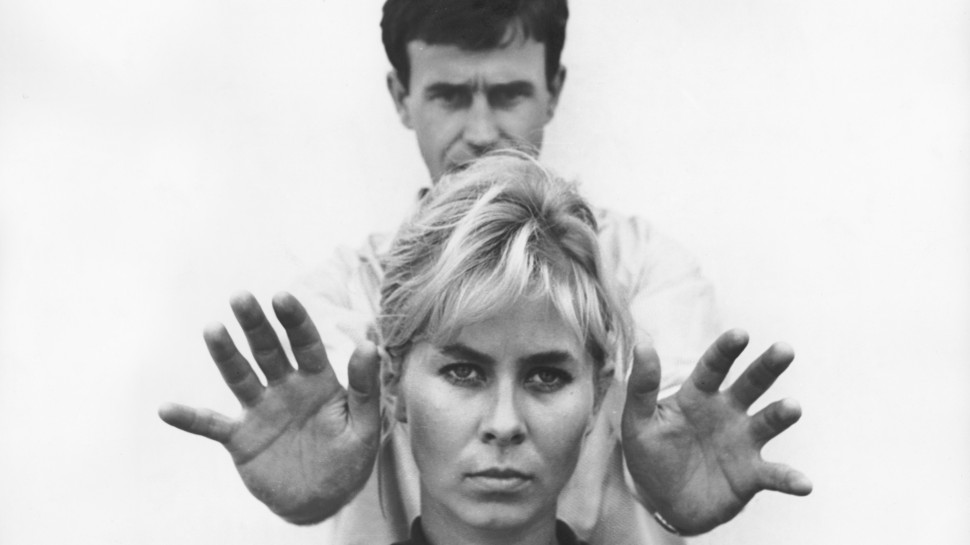

The Shout (19 The Shout (1978) |

One of the marvellous things about Skolimowski is that although he’s occasionally been forced to take on projects that he didn’t find particularly congenial even at the time (Gerard, King Queen Knave, Torrents of Spring), they’re very much the exception to the general rule, which is that the overwhelming majority of his films are utterly uncompromising visions by a uniquely distinctive artist. And yes, that’s not always going to chime with either critical or box-office appeal – although I’m delighted whenever he manages to crack that particular nut with films as good as Deep End, The Shout, Moonlighting, Essential Killing and EO. None of them were exactly blockbusters (although I don’t imagine he cares one iota about this), but I get the impression that their producers were very happy with how they performed.

Incidentally, Jeremy Thomas was behind three of those – The Shout was only his second feature, and he had to keep the budget low because his primary aim was to make an artistically prestigious festival award-winner and he hired Skolimowski with that end in mind, rather than because he was a box-office draw. But he was then delighted to discover that Skolimowski’s involvement helped secure a cast of a calibre way beyond what the budget would normally have stretched to – Alan Bates, Susannah York, John Hurt, Robert Stephens, Tim Curry and Jim Broadbent actively wanted to do it, as it looked far more interesting than most other things that were happening in the British film industry at the time. And Thomas and Skolimowski remained close friends, with Thomas later acting as executive producer of Skolimowski’s last three films.

And I made a point of mentioning Thomas in some detail because producers like that are an absolute godsend to a filmmaker like Skolimowski – in fact, The Shout was a wonderfully symbiotic project for both of them, as it put Skolimowski firmly back on the map while also giving Thomas’ then nascent career a hefty boost – not least because in addition to completely fulfilling its primary aim (the Special Jury Prize at Cannes comfortably met Thomas’ target there), it was also a decent-sized commercial hit.

Eo (2022) Eo (2022) |

After retiring for 17 years to paint, Skolimowski returned to filmmaking and to Poland in 2008 and has since made several successful films, including Four Nights with Anna (2008) and Essential Killing (2010). His most recent film EO (2022) has received particular acclaim and was nominated for an Oscar. Do you think this late recognition signals a wider reappraisal of Jerzy Skolimowski’s career? Do you see any modern filmmakers following in his footsteps?

I absolutely agree that EO has come along at just the right time. Essential Killing didn’t do badly either, but back in 2010 Skolimowski’s earlier work was still pretty hard to track down – you’d have to import a Polish DVD box set of the pre-1967 titles, for instance, and many of the later ones were unavailable anywhere – even a major film like Deep End hadn’t been seen for decades prior to the BFI’s 2011 revival. But as of the end of March 2023, I already have English-friendly Blu-rays of six of them (Walkover, Deep End, The Shout, Moonlighting, The Lightship, Essential Killing), and by the summer those should be augmented by Identification Marks None, Barrier, Hands Up! and EO, courtesy of the BFI and Second Run, plus what should be a significantly superior edition of Walkover to the barebones Polish one. And Le Départ is even on Netflix!

So whereas in the past any interest in Skolimowski rapidly came up against the considerable obstacle of lack of easy access to the bulk of his filmography, things are happily very different now, and any interest spurred by the success of EO and the retrospective can easily be followed up. And as someone who’s been an ardent fan of Skolimowski’s work since my teens, ever since I caught Moonlighting on its original cinema release because its backstory sounded fascinating, I couldn’t be happier about this, and I’m honoured to have played a small part in facilitating it.

Interview by Simon Hitchman, © March 2023 - please do not reprint or reuse without permission. |