<< continued from page 2

In Cannes, Truffaut met Georges de Beauregard, an enterprising producer willing to take a gamble on a young director. Truffaut introduced him to Jean-Luc Godard who proposed several projects, including an idea Truffaut had come up with based on a story he had seen in a newspaper. Beauregard liked the scenerio and bought the rights off Truffaut for 100,000 francs. Godard was an unknown however, so as an added guarantee, Beauregard insisted that Godard’s friends, who were now well established, appear in the credits. Truffaut was credited with the screenplay and Chabrol as artistic advisor.

A Bout De Souffle (Breathless) [1960]

....

|

More than any other film À Bout de Souffle (Breathless) (1960) exemplified the New Wave movement; serving as a kind of manifesto for the group. While the plot, reminiscent of a thousand Film Noir B movies, is simple, the film itself is stylistically complex and revolutionary in its breaking of traditional Hollywood storytelling conventions. All of the trademarks of the New Wave are evident: jump cuts, hand-held camerawork, a disjointed narrative, an improvised musical score, dialogue spoken directly to camera, frequent changes of pace and mood, and the use of real locations. As Godard said, the film was the result of “a decade’s worth of making movies in my head”.

À Bout de Souffle was a commercial and critical success, playing to packed houses in Paris, and winning the Silver Bear for Best Director at the Berlin Film Festival. Its stars Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg became fashion icons for the young, and audiences across the world responded to the picture’s iconoclastic spirit. Godard had taken his first step toward reinventing cinema.

Like Godard, Truffaut had a passion for American pulp crime novels and Film Noir. His own unconventional take on the genre began with his second picture which was adapted from a novel by David Goodis called Down There. This was a deliberate move away from what he felt the public expected of him after the autobiographical nature of his first film. Tirez Sur Le Pianiste (Shoot The Pianist) was packed with cinematic references and deliberate subversions of genre conventions. It was a chance for the director to enjoy himself and prove he wouldn’t be easily catagorized.

Although considered a classic now, Tirez Sur Le Pianiste baffled audiences at the time who were used to a more conventional style of storytelling. The film was not a financial success and Truffaut, who had planned to turn his company Les Films du Carrosse into a kind of New Wave studio, was forced to lower his expectations. From this time onwards he made it a rule only to produce his own films, and any projects sent to him, he referred to other producers.

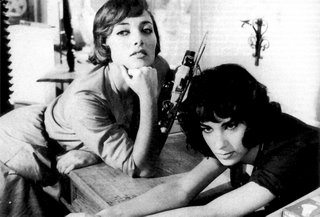

Les Bonnes Femmes [1960]

....

|

The start of the 1960’s saw the release of a diverse collection of New Wave films all featuring female characters at their centre. Typically unpredictable, Louis Malle followed Les Amants with Zazie Dans Le Metro (1960), a lively, surreal farce shot in colour. Adapted from a novel by Raymond Queneau, the story follows an eleven year old girl and her eccentric uncle on a mad cap chase around Paris.

Jules Et Jim [1961]

....

|

Claude Chabrol also reacted against his previous work with Les Bonnes Femmes (1960), an unusual mix of Hitchockian thriller and documentary realism, examining the ups and downs in the lives of four shop girls. The film details their hopeful but ultimately doomed attempts at finding romance.

Jacques Demy’s debut feature Lola (1961), set in the seaside town of Nantes, drew on musicals, fairytales, and the golden age of Hollywood for its inspiration, and set the tone for all his subsequent pictures. Featuring Anouk Aimee in the title role, this often downbeat tale of lost love and the machinations of fate was told with a joie de vivre that would become characteristic of Demy's unique cinematic oeuvre.

That same year, Francois Truffaut was planning Jules et Jim the story of two friends who both fall in love with the free-spirited but capricious Catherine. He had initially come across the semi-autobiographical book by Henri-Pierre Roche by chance in a second hand bookshop, had fallen in love with it, and considered making it his first feature. However, realising how difficult it would be to get right, he put it to one side until he had more experience under his belt. Now he had the experience and used it to create what would become one of the most famous and popular films of the French New Wave.

Jules et Jim (1961) was a stylistic tour de force, incorporating newsreel footage, photographic stills, freeze frames, voice over narration, and a variety of fluid moving shots executed to perfection by cameraman Raoul Coutard. Despite this, Truffaut stayed remarkably faithful to the source material. The unconventional love triangle at the centre of the story and the determination of Catherine (Jeanne Moreau) to find sexual satisfaction outside of society’s conventions caused much controversy at the time of the film’s release but did nothing to hinder the film’s success.

The Left Bank Group, from left: Alain Resnais, Agnes Varda, Armand Gatti, and Jacques Demy (holding camera, front right)

....

|

In the early 1960s, critic Richard Roud attempted to draw a distinction between the directors allied with the influential journal Cahiers du Cinéma and what he dubbed the “Left Bank” group. This latter group embraced a loose association of writers and film-makers that consisted principally of the directors Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnès Varda. They had in common a background in documentary, a left wing political orientation, and an interest in artistic experimentation.

L'Annee Derniere A Marienbad (Last Year At Marienbad) [1961] .

|

Another associate of the group was the Nouveau Roman novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet. In 1961 he collaborated with Alain Resnais on L’Annee Derniere A Marienbad (Last Year in Marienbad). The film’s dream-like visuals and experimental narrative structure, in which truth and fiction are difficult to distinguish, divided audiences, with some hailing it as a masterpiece, and others finding it incomprehensible. Despite the critical disagreements, the film won the Golden Lion at the 1961 Venice Film Festival, and its surreal imagery has become an iconic part of film history.

Chris Marker began making documentaries in the early 50’s, collaborating with his friend Alain Resnais on Les Statues Meurent Aussi (1950-53), which begins as a simple film about African art and gradually changes into an anti-colonialist polemic. Over the following years he developed a unique essay style of documentary filmmaking. His one fictional film, La Jetee (1962), a science fiction story about a time traveller, composed almost completely of still photographs, has become a classic in its own right.

Agnès Varda is the most celebrated female director to be associated with the New Wave. She began as a photographer, then turned to the cinema and directed La Pointe Courte (1954), a low budget documentary-like feature film about the break up of a marriage which, in its production method and style, presaged the coming New Wave. Over the following years, she made a number of shorts and documentaries, before directing Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962). This real time portrait of a singer set adrift in the city as she awaits the results of a life or death medical report became one of the benchmarks of the Nouvelle Vague movement.

Adieu Philippine [1962]

....

|

In December 1962, Cahiers du Cinéma published a special issue on the “New Wave”, which included long interviews with Truffaut, Godard and Chabrol, and a list of 162 new French directors. Among the first time directors discussed were Jacques Doniol-Valcroze (L’eau a la Bouche (1960)), Pierre Kast (Le Bel Age (1960)), Luc Moullet (Un Steack Trop Cuit (1960)), Jean-Daniel Pollet (La Ligne de Mire (1960)), Jean-Pierre Mocky (Les Dragueurs (1960)), and Jacques Rozier (Adieu Philippine (1962)). The success of the early New Wave had opened the gates for a generation of unknown directors to break through into what had previously been a very closed industry. Films were now being made by young people, for young people, and staring young people.

Inevitably, there was a media backlash. The failure at the box office of Tirez Sur Le Pianiste, Une Femmes est une Femmes and other high profile releases gave the press ammunition to attack the movement. They reproached the young directors of the New Wave for making films that were “intellectual and boring”. At the same time the old guard believed it was making a comeback with a string of successful films beginning with Rue des Prairies (1960), staring Jean Gabin.

There was dissent too at Cahiers du Cinéma. Most of its leading writers were now directors and no longer had the time to devote to writing for the magazine. As a result, by the early 60’s, a second generation of young cinephiles had replaced the first group. This new group did not always share the same opinions as its predecessors, leading to clashes with editor in chief, Eric Rohmer.

Supported by the new writers, Jacques Rivette took over as editor, and the sense of community at the review fractured. The production of the New Wave group film Paris Vu Par (1964) – a series of sketches by different directors – signalled the change. Rivette, and Truffaut who had supported him, were symbolically excluded from contributing. The split had begun. Each of the filmmakers associated with Cahiers now went their own, increasingly divergent, ways.

Anna Karina in Vivre Sa Vie (My Life to Live) [1962]

....

|

By the mid-60’s Jean-Luc Godard was probably the most discussed director in the world. The films came in rapid succession, each one a further step towards a personal reinvention of cinema. After À Bout de Souffle, came a political thriller, Le Petit Soldat (The Little Soldier) (1961), a technicolour wide screen musical, Une Femme Est Une Femme (A Woman is a Woman) (1961), a social drama about prostitution, Vivre Sa Vie (One Life to Live) (1962), and a war film, Les Carabiniers (The Soldiers) (1963).

These early films had made a star out of Belgian-French actress Anna Karina, whom Godard had married in 1961. With his next film, Le Mépris (Contempt) (1963), he reinvented Brigitte Bardot’s public image, giving her the chance to prove she could act. The film - a story about the breakup of a relationship set against the pressures of commercial filmmaking - became Godard’s biggest box office success, ensuring continued financial backing for his prolific output.

In the following years, Godard continued to make films that established him as the definitive New Wave director. After the lush Mediterranean scenery of Le Mepris, he went back to the streets of Paris, showing a gritty view of the city in crime caper Bande A Part (Band of Outlaws) (1964), and an alternative view in the dystopian sci-fi feature Alphaville (1965).

Weekend [1967]

|

Next came a road trip to the South of France for the brilliant Pierrot Le Fou (1965). Pairing Jean-Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina and abounding with ideas and references to both high and low culture (it even features a cameo from B movie maestro Sam Fuller), the film was a culmination of all the director’s radical filmmaking techniques up to that point.

Godard’s political views became increasingly central from now on. Masculin, Feminin (1966), was a study of contemporary French youth and their involvement with cultural politics. An intertitle refers to the characters as “the children of Marx and Coca-Cola.” Next came Made in the U.S.A (1966), a playful crime story inspired by Howard Hawks’s The Big Sleep (1945).2 ou 3 choses que je sais d'elle (Two or Three Things I Know About Her) (1967), starred Marina Vlady as a woman leading a double life as housewife and prostitute. Le Chinoise (1967) focused on a group of students engaged with the ideas coming out of the student activist groups in contemporary France.

Later that year, Godard made a more colourful political film. Weekend (1967) follows a Parisian couple as they go on a trip across the French countryside to collect an inheritance. What ensues is a darkly comic, sometimes horrific, confrontation with the tragic flaws of the bourgeoisie. Weekend’s enigmatic closing title sequence concludes with the words “End of Cinema”, a declaration which signalled an end to the first period in Godard’s filmmaking career.

continues on page 4 >>

|