|

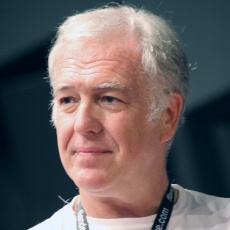

Geoff Andrew, BFI Head of Film Programme |

To celebrate the British Film Institute’s major retrospective of the work of François Truffaut, newwavefilm.com interviewed the season’s curator and BFI Southbank Programmer at Large, Geoff Andrew, who talked about Truffaut's enduring appeal, his influences, and what makes him one of cinema's greatest and most fascinating directors. The BFI's François Truffaut: For the Love of Films season will be taking place throughout January and February.

We have partnered with the BFI to offer 2 for 1 tickets using the code Truffaut241 at the BFI website.

|

Bernadette Lafont and Gérard Blain in Les Mistons (1957) |

As the curator of this two month François Truffaut retrospective at the BFI, can you give a brief overview of what the season will include and recommend some highlights for our readers?

It includes all his features, as well as his short films: Antoine and Colette, which he made as part of the Antoine Doinel cycle, Une histoire d'eau (A Story of Water), which he made with Jean-Luc Godard, and also Les Mistons, which is not actually his first short — his first short Une Visite is not available — but we’re showing what is his acknowledged first short, which is Les Mistons. It stars Bernadette Lafont and Gérard Blain who were a couple at the time. It’s her first time on screen and she went on, of course, to work with Truffaut years later in Une belle fille comme moi (A Gorgeous Kid Like Me), which we’ll also be screening. So we’re showing everything we can, everything available. As far as highlights, there’s Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows), his first feature with Jean-Pierre Léaud, which is semi-biographical and is an absolute classic of French cinema, and Jules et Jim which people love. We’re reviving both of those for an extended run. Other particular favourites of mine include L'Enfant sauvage (The Wild Child), Day for Night, and I particularly like La Peau douce (The Soft Skin), with the late François Dorléac, Catherine Deneuve’s sister. Shoot the Pianist, of course, is another classic. It’s probably his most New Wavey film — irreverent and poignant at the same time — and sort of an upturning of the crime thriller. I think there was a little bit of tailing off towards the end of his career, but in re-visiting his films I found a lot of them stood up very well. And there were also a few I hadn’t seen before, which I had read not great reviews of in the past, and quite a lot of them were pleasant surprises. You know, they were all rather better than I expected. So there is plenty to enjoy there I think.

|

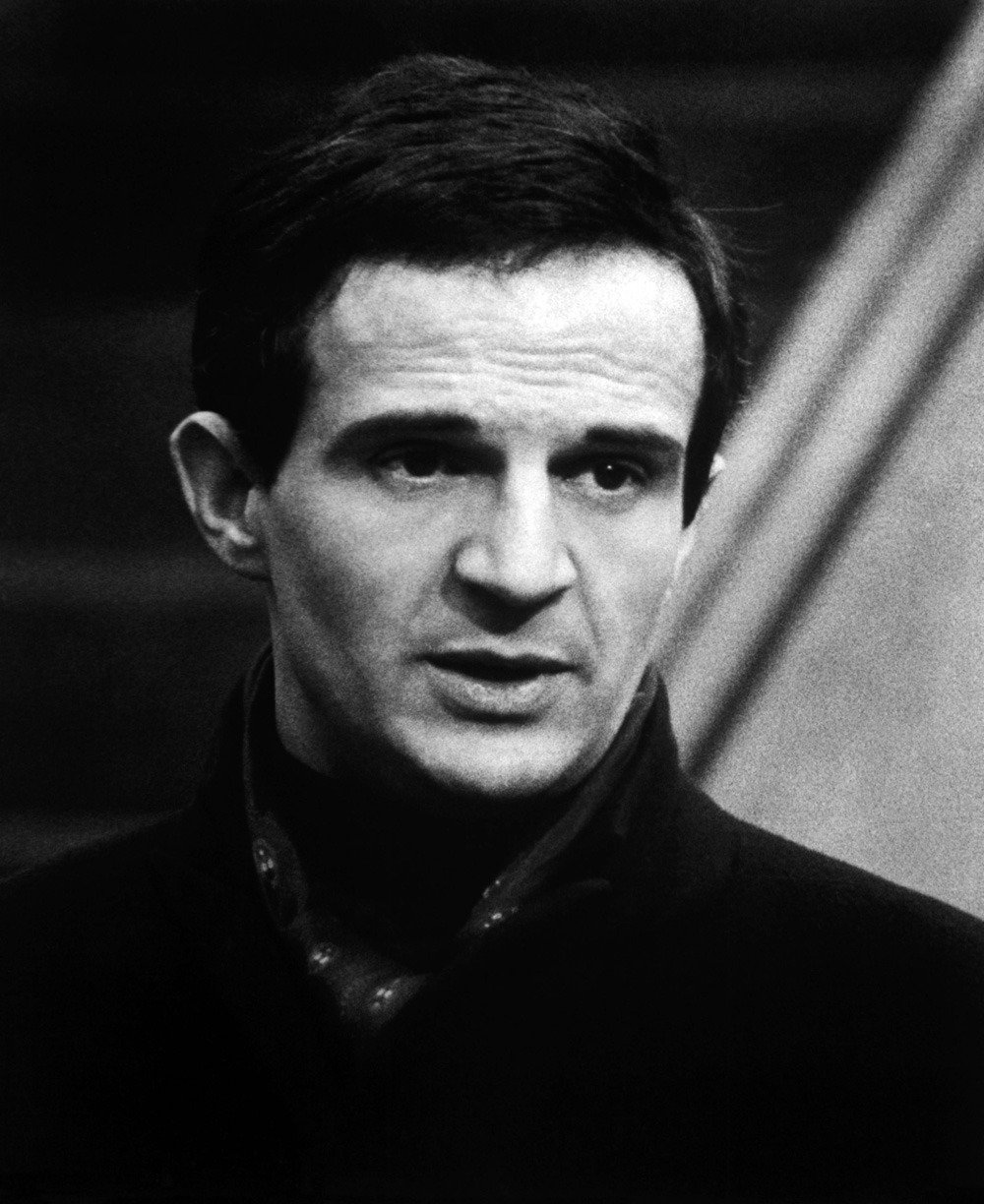

François Truffaut |

Before discussing Truffaut’s work I wondered if you had any thoughts about Truffaut as a person. From my observation he’s somebody with whom many people feel a close personal connection, which is quite unusual for a film director. Is that something you’ve noticed?

Yes, I never got to meet him myself, but I think he seems to have been somebody who was very passionate about cinema. Cinema had, in a sense, saved his life because he could have become a delinquent, but because of his discovery of film, and indeed of literature, and with the help of the critic André Bazin, he was saved from the delinquent life and he became a film critic and a filmmaker. And he was a very passionate critic and a very passionate filmmaker, but also, I think, a very humane one. One of his idols was Jean Renoir and you can sort of tell that from some of the films. They’re never sentimental but he has a great compassionate interest in his characters even when they’re not actually very nice people, and deeply flawed, or possibly insane. He goes by that saying from Renoir’s La Règle du jeu: ‘everyone has their reasons’. And I think the other thing is that he did act in a number of his own films. He was in L'Enfant sauvage (The Wild Child), Day for Night and The Green Room, so one can see him on screen. And there’s something about him in those films which is quite likeable. He’s not somebody who tries to ingratiate himself with the audience at all, he tends to act in a very deadpan way, but he comes across as having a lot of integrity, and again, compassion. And I think of all the big French New Wave directors, he probably made the most accessible films. So I think people like them because of that as well. He was an entertainer — so in the 60s was Godard, and Rohmer, and Chabrol, and Rivette — but I think Truffaut’s films are perhaps — I wouldn’t say the most conventional because they’re actually quite unconventional — but they’re not perhaps as formally challenging as some of the other films of the New Wave. I think because of that they’re more audience friendly. So people probably like him because of that, as well.

The Antoine Doinel cycle is one Truffaut’s most unique and popular contributions to cinema. Many see the Antoine Doinel character as a stand-in for Truffaut himself. Do you share this view?

|

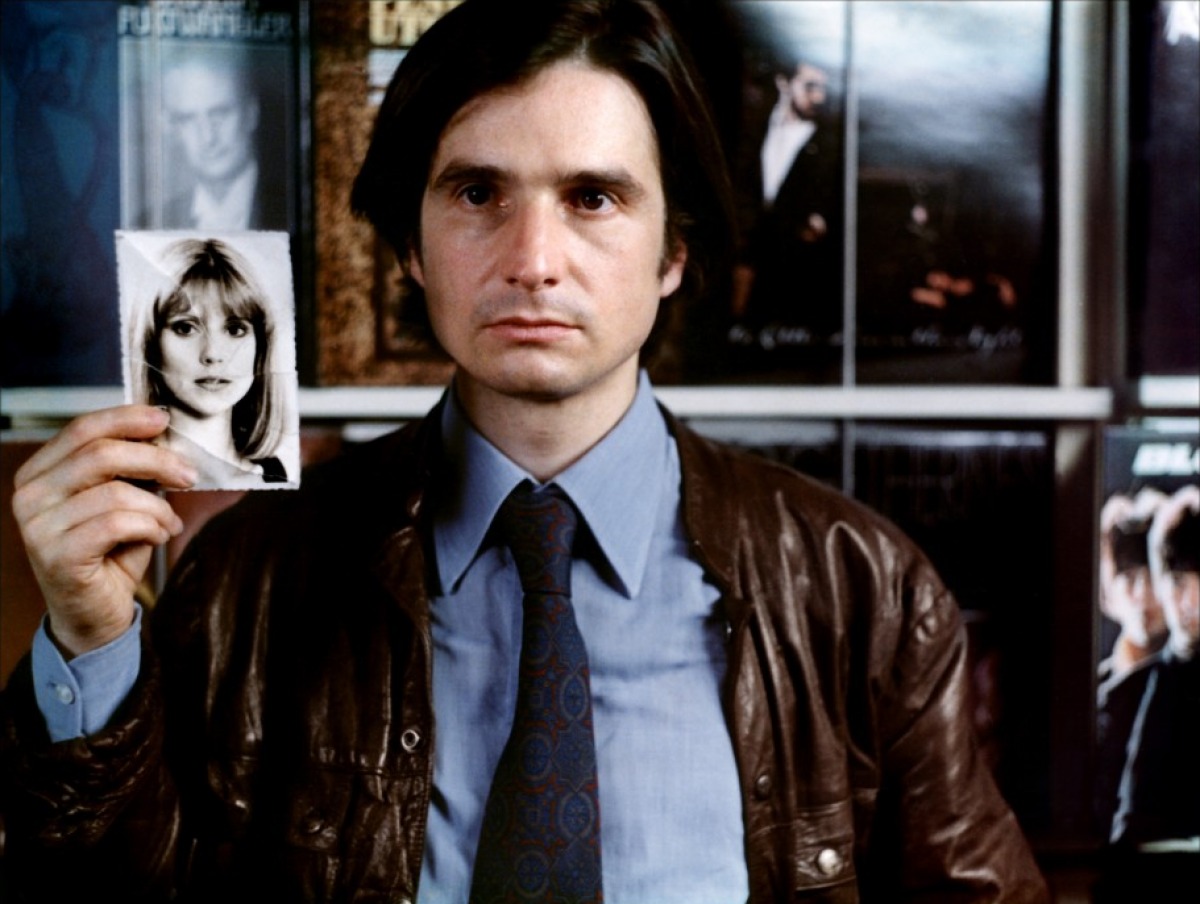

Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel in Love on the Run (1979) |

I think as the cycle progresses the character becomes more and more independent of Truffaut. Certainly in The 400 Blows we get the feeling that there’s a lot of Truffaut in that character, and maybe also in Antoine and Colette. But by the time you get to Stolen Kisses the character is more comic. His clumsiness in relationships, and indeed in his work, becomes a source of comedy. I think in the later films he’s much more fictional, and Truffaut becomes more critical of him as the series progresses, particularly his self-centeredness, and his deceptions towards the women in his life. I think — if there is an autobiographical element in those later films — it would have to be self-critique. But also, because the character is always played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, there’s probably quite a lot of Léaud in the character as well, particularly as the films go on. So I think they become less autobiographical as the series goes on. It’s interesting that he’s really quite critical of him by the time he gets to Bed and Board, and then in the final one, Love on the Run. Most people see that as the weakest of the films, but it’s interesting because by then the character has actually written about his experiences and the film becomes a critique not only of the character, but also how he has turned his own experiences into art, into literature. Colette, played by Marie-France Pisier, reappears in that final film, and she sort of tells Antoine, you’ve changed things so much and it’s all to make yourself look better. So there’s an element of self-critique there.

As you mentioned, Truffaut idolized Jean Renoir. In what ways do you think Renoir influenced Truffaut? And are there any films you think are particularly representative of that influence?

|

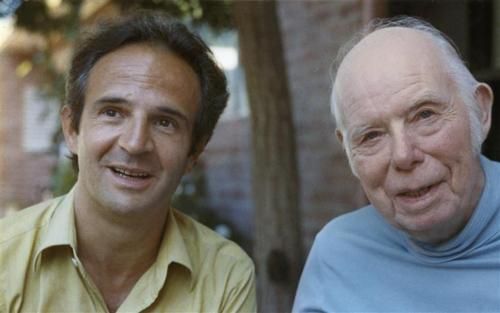

François Truffaut and Jean Renoir |

Well, I think it’s more in an attitude towards people, this idea that ‘everybody has his reasons’. There’s a lot of compassion in Truffaut’s films, even towards very flawed characters. It’s one of the most interesting things about Truffaut, I think, that he’s happy to show us his characters warts and all, and I think this compassionate interest in people, even flawed people, is something you also see in Renoir’s films.

I think there’s a similarity also in his attitude towards narrative. Renoir, in films like La Règle du jeu (The Rules of the Game), or Boudu Saved from Drowning, he’s prepared for the narrative to go all over the place. He’s not a filmmaker who believed a film had to have three acts, and I think Truffaut is like that too. Some of the narratives of his films are very freewheeling and he allows them to go off on all sorts of tangents. And then, finally, I think Truffaut was very interested in community in the same way that Renoir was. He made quite a lot of films where there are groups of people, either living together, or working together, and I think that’s something that’s probably taken from Renoir.

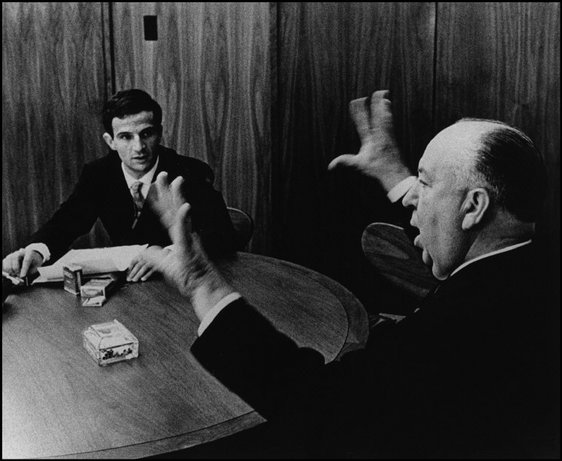

Truffaut also revered Alfred Hitchcock and after interviewing him in the early 1960s Truffaut’s films in that decade such as The Soft Skin, Fahrenheit 451 and The Bride Wore Black become increasingly influenced by Hitchcock. Some people, Claude Chabrol for instance, have wondered if the influence was altogether positive. Do you think there might be something incompatible between Truffaut’s innately realistic and human cinematic vision and Hitchcock’s more calculating style, or do you think Hitchcock actually brought out the best in Truffaut?

|

François Truffaut and Alfred Hitchcock |

I think it varies. I mean Truffaut’s crime films are nothing like most of Hitchcock’s crime films. Hitchcock famously liked to storyboard every scene, he wasn’t particularly interested in the actors, and he had a very fixed idea of what he wanted to do. I don’t think Truffaut was like that. I think the Hitchcock influence can be seen in the editing of some of Truffaut’s films, particularly in a film like The Soft Skin which feels very Hitchcockian in its editing style, and also in Fahrenheit 451. And when Hitchcock spoke to Truffaut it was the early 60s. This was a time when he had fairly recently made Vertigo, and he was in the process of making Marnie — those two films are very much about obsessions. I think that plays out in films like Mississippi Mermaid and The Bride Wore Black. Like Hitchcock, Truffaut is interested in obsession. You can see it in a film like The Story of Adèle H., which is not a crime film at all but it’s a study of obsession. I don’t know whether Chabrol was right; I mean, you know, Chabrol was also extremely obsessed by Hitchcock. He made an entire career more or less on that with variable results, though often with very good results. I don’t think Truffaut’s interest in Hitchcock did a lot of harm because it never dominated the films, in the same way that the Renoir influence never dominated the films. And, in fact, you’ve almost always got Hitchcock and Renoir in all the films, but you’ve also got a lot of Truffaut, of course.

|

Two English Girls (1971) |

When he was a critic in the 1950s Truffaut was very critical of literary adaptations in French cinema and the so-called ‘tradition de qualite’ genre of films. In what ways would you say Truffaut’s approach to literary adaptation was different or unique?

It’s almost like he’s very open about literary adaptations in that he uses voice over in quite an idiosyncratic way — sometimes it’s an objective narrator, sometimes it’s a mix of narrators. He just seems to have been fascinated by literature, and that becomes a part of his work. He’s not pretending, which is very different to the normal sort of quality adaptation where you adapt a book, but you don’t draw attention to the fact that it’s an adaptation. Truffaut actually savours the words. You can see it even in the credits of Fahrenheit 451 where you get lots and lots of book covers. I think one of his most underrated films is Les Deux Anglaises et le Continent (Two English Girls) which is another adaptation of a book by Henri-Pierre Roché who wrote Jules et Jim. It actually deals with somebody, as did Love on the Run, who turns their experiences into a book. It’s sort of very self-referential, and it shows how Truffaut makes it quite clear when he’s doing an adaptation that that’s what he’s doing.

The season will also include screenings of a series of films that Truffaut lauded in his film criticism or which were particularly influential on his own work. Can you tell us about some of the films you’ll be showing and why you chose them?

I went through Truffaut’s book — there’s an anthology of his reviews called Les Films de ma vie (The Films in my Life) — and chose some classics from that. It’s films he particularly liked by filmmakers he admired, so we’ve got Hitchcock and Renoir of course, but also Orson Welles, Rossellini, Max Ophuls, Cocteau, Howard Hawks, Bergman, Nicholas Ray. They’re just films that he loved, and in most cases they happen to be films that I love as well — he had pretty good taste in films it has to be said.

|

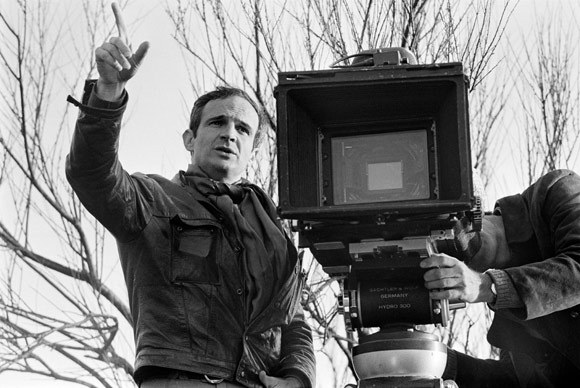

François Truffaut directing |

These films recall the fact that as a critic at Cahiers du Cinema, Truffaut was one of the originators of auteur theory. Do you think in his later career as a director he lived up to the ideal of an auteur with consistent themes and a distinct cinematic style, or did he evolve multiple styles over time to suit each picture?

Yes, it’s interesting. When you look at a Chabrol film, or a Rohmer film, or indeed a Godard film — although it has to be said that Godard has had various styles over the years — they’re very, very distinctive. In the case of Truffaut, it’s less distinctive in a way. I mean he does — perhaps more than any of the others — he does pay tribute to filmmakers of the past and the stylistic traits of earlier cinema. I don’t know any other modern filmmaker who used as many iris shots as Truffaut did. And he worked with very good cinematographers, including Néstor Almendros, and some of the films look very nice, but I’m not sure they had a particularly idiosyncratic style that one can immediately identify as his. But, if you think about it, in his concerns, in his themes, and in his approach towards people, then yes, he definitely could be termed an auteur. His films deal with the same sort of themes over and over again, so certainly in terms of his interests and his preoccupations, he was definitely an auteur.

Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard were close friends in the early years of the French New Wave but had a falling out in the early 70s when Godard wrote a letter to Truffaut after seeing Day for Night in which he accused him of being a sell-out for embracing commercial mainstream cinema. Do you think there is any validity in what Godard said, that Truffaut had increasingly embraced mainstream cinema and become the kind of director he had once criticised, or do you think Godard misinterpreted Truffaut vision and what he was trying to do as a film director?

Well this was when Godard was going through his Maoist phase and I think he was pretty much against everybody at that time except perhaps for Anne Wiazemsky and one or two other people. But if you compare Day for Night — which is a joyous film about filmmaking, but also one that admits to the lies that filmmakers have to tell in creating this artifice, the compromises that are made, and the difficulties and anxieties involved — when you compare that to Le Mépris (Contempt), which is Godard’s own film about filmmaking, it seems more accurate in many ways. I like Le Mépris very much, but the portrait of filmmaking in that is rather less persuasive than the portrait of filmmaking in Day for Night. I mean, the film of The Odyssey that we’re seeing being shot (in Le Mépris) is ludicrous — it doesn’t look like any film that has ever been made apart perhaps from Le Mépris itself, you know. Whereas Day for Night does look like a proper film is being made. And I think Day for Night is not only one of Truffaut’s most enjoyable films, but actually it really does feel very truthful in many ways. It’s affectionate, but I don’t think it’s glamorizing filmmaking.

You’ve touched on this already, but I wanted to ask if there are any Truffaut films you particularly like, or any you feel have been overlooked and deserve more attention?

|

Pocket Money (1976) |

Well, as I mentioned, my favourites are Day for Night, La Peau douce, and L'Enfant sauvage. They’re all pretty well known I suppose. Of the ones that are perhaps lesser known, I would say The Story of Adèle H., The Green Room, and Les Deux Anglaises et le Continent are all fascinating films and certainly deserve a bigger audience than they’ve probably had. I think nearly all the films are very watchable, and all of them have great points of interest. Some of them are a little more uneven than others. I was interested to see Pocket Money, which I’d never seen. If you read some reviews of it you’re told that it’s terrible, but actually it’s not terrible at all. There are some strange moments which for me don’t quite work, but a lot of it is actually quite good and rather ahead of its time in its concern with the effect of neglect and abuse on children. It’s a far more interesting film and rather more rewarding than a lot of the reviews at the time suggested. I think he’s a filmmaker who is definitely worth reassessing. His films may have seemed one way when they were made but all these decades later, some of them I think have stood up very well. I was watching the other day Petite Maman, the film by Céline Sciamma, about children and their relationship with adults. I won’t say what I thought of the film because that is neither here nor there, but it’s possibly a film that is following on from what Truffaut was doing when he was making films with children in some ways, and at the time he was more or less doing it alone.

So do you think Truffaut had a lasting influence on cinema?

I think Truffaut, like all the New Wave filmmakers, particularly influenced French cinema. They permeated and changed French cinema. I mean French cinema was very good before they came along, but they introduced less well-known, untrained actors, and they started filming on location, and a lot of good French cinema has continued doing those things. It’s one reason why French cinema is so rewarding, because they saw cinema as an art, and they showed that you could make films about ordinary people, whether that’s Chabrol’s studies of the bourgeoisie, or Rohmer’s studies of the sorts of people who don’t usually get put into films. All they’re doing is wondering whether they’re in love with somebody or not, but these are films about life as most of us experience it, and the French cinema has done that much more than the American cinema which has dealt with heroes, and these days, sadly, super heroes. You know, it’s got nothing to do with life as we live it; it’s escapist cinema, whereas these people made films which weren’t escapist cinema, and the French cinema still manages to do that.

Interview by Simon Hitchman, © December 2021 - please do not reprint or reuse without permission. |