|

Geoff Andrew, BFI Head of Film Programme |

To enjoy 2-for-1 tickets to any films in the season simply quote PICCO241

when ordering tickets via phone or the BFI website.

|

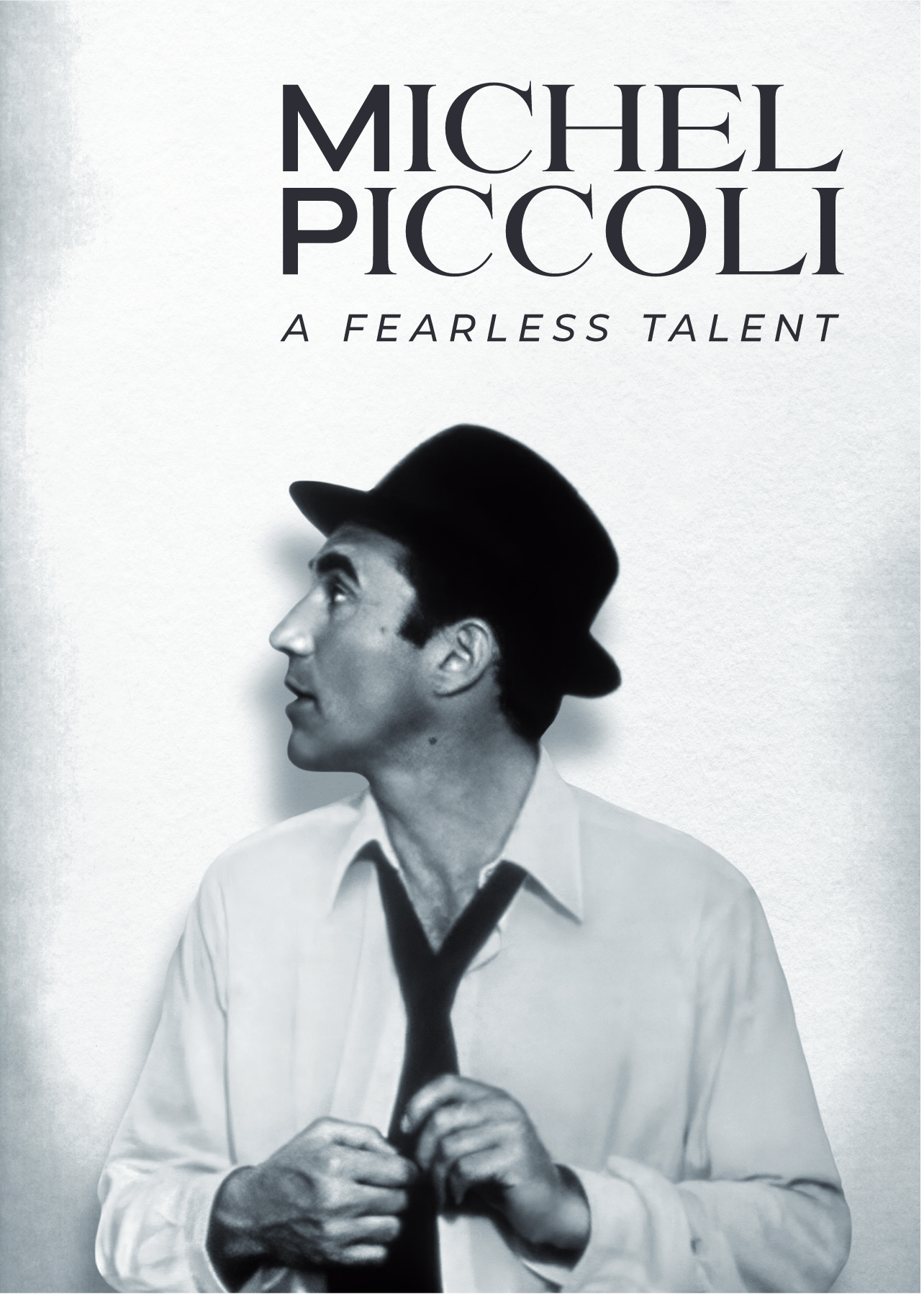

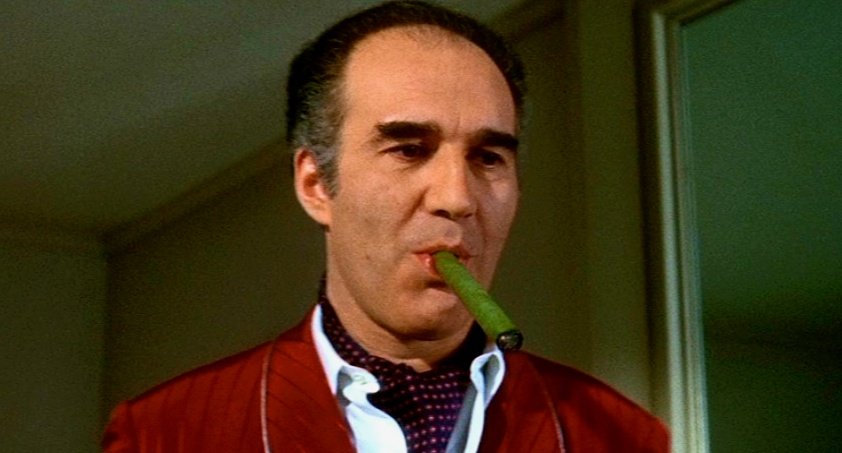

Michel Piccoli - poster for the current BFI season |

As the curator of this month-long Michel Piccoli retrospective at the BFI, can you give an overview of what the season will include and recommend some highlights for our readers?

Well, there are about sixteen films in the season, all of them highlights drawn from Piccoli’s career, plus, of course, an extended run of Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris.

It must have been difficult choosing just sixteen films considering how prolific Piccoli was.

Yes, it was. I’ve wanted to do the season for about fifteen years, and we’ve only just got around to doing it, but I remember some years ago doing an initial wish list and there were about thirty films on it. We never do complete seasons for actors, but thirty films are what you’d be doing for someone like Cary Grant, or James Stewart, or Katherine Hepburn, which suggests how important we consider Piccoli to have been.

In his 70-year career, Piccoli appeared in over 200 film and television productions and worked with just about every notable director in French and European cinema of his time. What was it about him, in your view, that made him such a distinctive actor and somebody that so many of the greatest filmmakers wanted to work with?

|

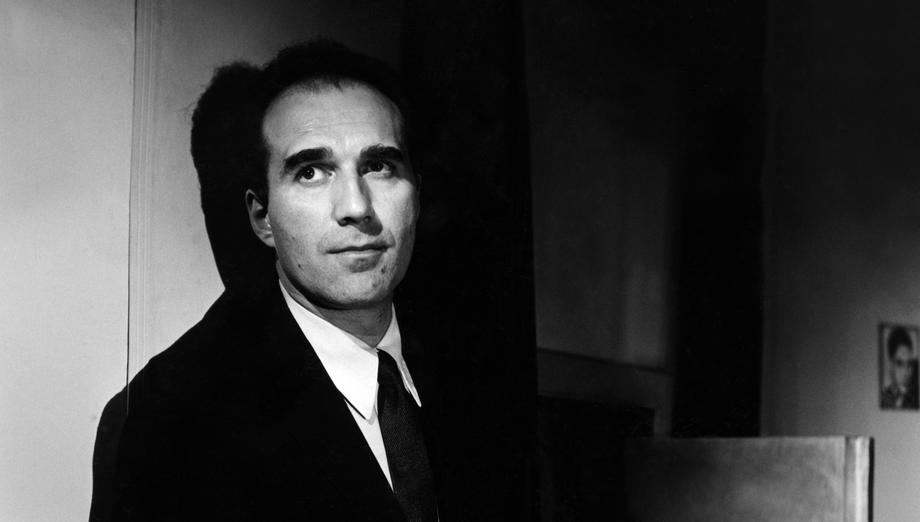

Michel Piccoli in Le Doulos (1962) |

I think it’s partly his ability to convey a lot by doing very little. He’s mainly a very understated actor. He can do a lot with his eyes. He often doesn’t need to be saying very much. I’m giving a talk on him, and I’ve chosen a few clips. One clip I liked very much but ended up not using was from Melville’s Le Doulos where he’s confronted by Belmondo who is holding a gun on him and obviously intends to kill him. Piccoli conveys the victim’s thoughts and quiet panic incredibly well. He doesn’t have a lot to say but suggests a lot just with the tiniest of smiles and the use of his eyes. He really could do a lot with a little, and I think that’s why filmmakers wanted to work with him. He had a very naturalistic style of acting, a very understated naturalism. Also, he was very versatile and made all sorts of different films believable, different sorts of characters but also different sorts of films. I mean if you think about it, he was in crime films, he was in comedies, he was in musicals, he was in serious dramas - he was in some really excessive films, and he was in some really restrained films, and he seems to have been at home in all of them. While I was thinking about this, I was actually reminded a bit of Cary Grant, who made everything look very easy, as if he wasn’t acting at all. But just as Cary Grant could play a range of characters and make them convincing, even though he always remained Cary Grant, Piccoli can play a range of characters, even though he always remains Michel Piccoli - and yet somehow he always manages to make those characters completely convincing. It’s sort of like he’s drawing on something in himself that overlaps a little with the character he’s playing.

|

Piccoli and Catherine Deneuve in Belle du Jour (1967)

|

Piccoli initially made his name acting in the theatre and appeared in a few small parts in films in the late 1940s and early 50s, but it wasn’t until Luis Bunuel cast him in Death in the Garden in 1956 that his film career took off. This was the first of six films Piccoli made with Bunuel, including one of his best-known roles in Belle de Jour (1967). Why do you think Bunuel liked to work with Piccoli so much, and what made him so memorable in these films?

Well, it’s interesting actually isn’t it, because in three of the Bunuel films – The Milky Way, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, and The Phantom of Liberty – he’s actually in very small roles, but he still makes his mark. I think they must have shared, not necessarily a world view, but there was an anti-establishment side to Bunuel, and I think the same was true of Piccoli. He made a number of films with Marco Ferreri who was certainly anti-establishment. I think what Bunuel and Piccoli probably shared was a great deal of mischief.

In Bunuel’s films, and throughout his career, Piccoli often played cruel, corrupt characters, but in real life he appears to have been quite the opposite. I wondered if you could comment on what kind of person Piccoli was offscreen?

His parents were musicians. He became a member of the set in Saint-Germain-des-Prés with Sartre and de Beauvoir and Boris Vian and Juliette Gréco, who he married, so he obviously had a certain sophistication. He was also a member of the communist party, so he was clearly a very intelligent man who thought about life seriously and doesn’t appear to have been a particularly conformist person. But I don’t know that much about him. I met him twice. Once was at the French Institute in London for the release of Manoel de Oliveira’s I’m Going Home. De Oliveira and Piccoli came over, and there was this reception at the French Institute. I was there, and I remember speaking to Piccoli who was mainly speaking with great affection and admiration for de Oliveira, who was then 93 but still very energetic. The other time I met him more formally. I met him for an hour for the release of La Belle Noiseuse, and he seemed absolutely charming and very intelligent and articulate. I don’t think he was like his characters that much. I mean he was so persuasive as an actor that we probably think he was like some of the characters, but he certainly wasn’t like all the characters, because they’re so very different. Yes, he could play cruel and corrupt and slightly perverse people, but I’ve never heard anything to suggest he was like that in real life. I think he was a very brave actor, and he would do whatever was required for a role if he thought the film was worthwhile.

His bravery or fearlessness seems to have been one of his defining characteristics as an actor.

Yes, you only have to see films like Themroc, or La Grand Bouffe, or even – I’ve included it in the season even though he’s only in the film for about fifteen minutes – A Room in Town, the Jacques Demy film, where, without giving away a wonderful spoiler, the final moments of his part in that film are quite extraordinary. He’s wearing this ridiculous green suit and red hair wig and beard and he looks like a demon but is actually utterly convincing. It’s funny how even in a film which is both musical, and a very intense melodrama, he still manages to take us with him. And even though he’s described as monstrous by the character’s wife, and we see that monstrous jealousy and violence in him, he still makes him somehow a sympathetic human person.

|

Piccoli and Brigitte Bardot in Le Mépris (1963) |

The part that made Piccoli an international star was his role opposite Brigitte Bardot in Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris. People often praise Bardot’s performance in the film or note how good Jack Palance or Fritz Lang are, but Piccoli is less often mentioned. How successful, in your view, is he in portraying the complex character of the writer Paul?

I think he’s absolutely wonderful. I’ve been watching it again to choose clips for my talk, and I can see why people talk about Bardot. For one thing, people didn’t take Bardot very seriously as an actress, but in that film, she showed that she could definitely act. And, of course, Palance - well, he doesn’t really belong in a Godard film, but he’s playing this sort of caricature of a producer, and he does it with great gusto. But Piccoli’s performance is altogether more subtle than either of those, I think. The great thing about Piccoli, and you see this in so many of his films but particularly in this one, is you can see him watching and listening to other people, and you can see him taking in what he’s hearing and seeing and thinking about it, and then responding. And his performance in responding to this sudden realisation that his wife is somehow turning against him, and his complete bemusement at this, is very convincing. It’s an incredibly quiet performance in many ways, but very detailed, very meticulous, and very controlled. And I think he is the best thing in the film, along with the lovely score and the cinematography. But in terms of the performances – the others are perhaps more noticeable, more conspicuous because of their slightly unusual nature – but his is the performance that holds the film together.

A lot of his characters appear to be self-controlled, but there always seems to be a lot going on beneath the surface.

Yes, with the sense that there might be some underlying anxiety or insecurity. Many of his characters seem very urbane and sophisticated and bourgeois, but there’s very often hints that all is not well behind that façade. And that comes through very well in Le Mépris, I think.

|

Piccoli and Yves Montand in Vincent, François, Paul and the Others (1974)

|

Piccoli received great acclaim for his collaborations with the director Claude Sautet on films like The Things of Life, Max et les Ferrailleurs, and Vincent, François, Paul and the Others. What does Piccoli bring to these Sautet films that make his performances so compelling?

It’s really the combination of Piccoli’s subtlety and Sautet’s subtlety. They were a very good match for one another, even when Sautet was sort of working in genre, which he didn’t do that much. It’s really sad that Sautet is not better known outside of France. I put on a season of his work some years ago, and it was something of a revelation because his films, with a few exceptions, are not very well known here. And the ones with Piccoli, they’re not difficult, they’re not arty in the conventional sense of the word, but they are definitely works of art, and very astute psychological studies, and also social studies. In a way, both Sautet and Piccoli are absolute professionals, really fine craftsmen who never felt the need to use hyperbole. Those films are terrific, and you can see why Sautet would want to work with Piccoli. I haven’t been able to watch all of the films they made together again, but I did rewatch Vincent, François, Paul and the Others, and he is remarkable in that when confronted with his wife who is quite brazenly cheating on him. He’s not playing a sympathetic character. I mean, it turns to domestic violence and sexual violence, but at the same time, you feel that this guy is really cracking up. He becomes terrible to his wife, and he starts being cynical towards his friends, and he’s really beginning to lose it, but he makes this rather cold character really very understandable, and you sort of feel for him, even though he’s not particularly sympathetic.

|

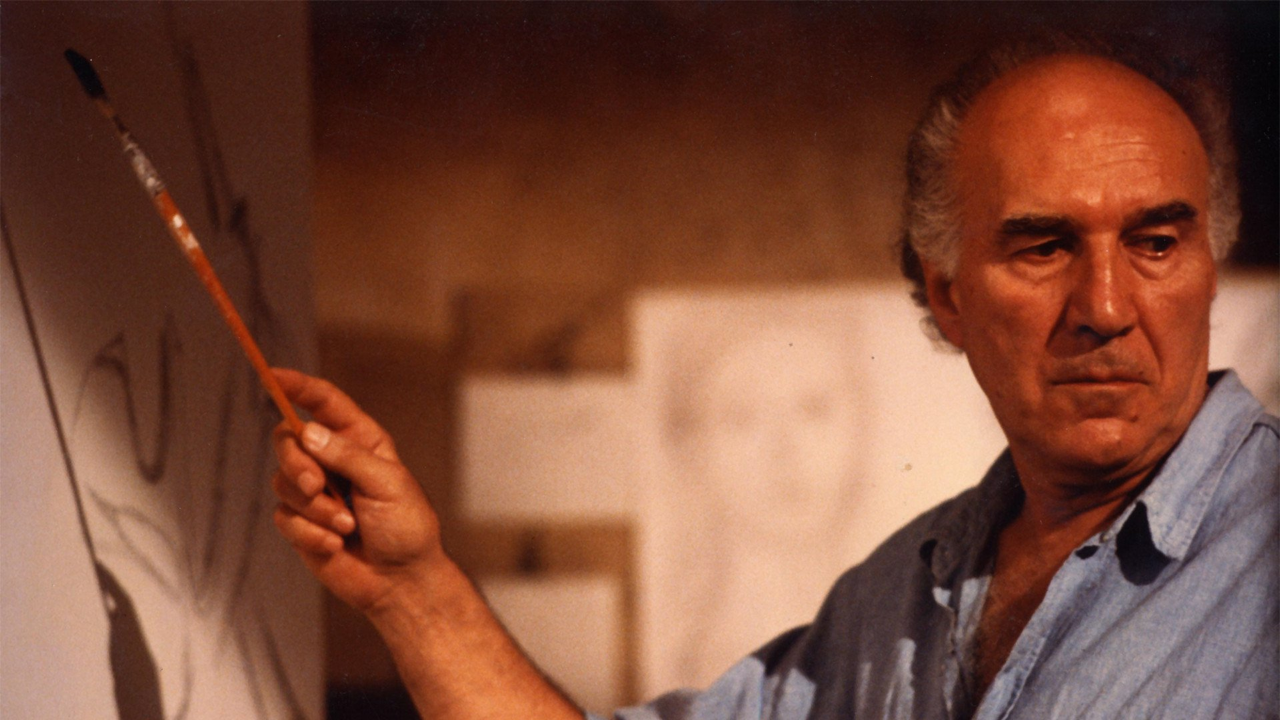

Piccoli in La Belle Noiseuse (1991) |

Piccoli’s career went from strength to strength from the 1970s until 2014 when he finally retired from acting. There’s a huge variety in these films and the parts he played in them, but I wonder if you discern a consistent Piccoli persona or personas running through these films?

I don’t know. What is consistent is Piccoli himself. I mean, he plays characters who are often very different. If you think about it, he plays cops, he plays gangsters, he plays jealous husbands, he plays the Pope, he plays an artist who has been suffering from artist’s block for several years and basically cracks up and turns into a cannibal, but it’s always Piccoli. And what’s consistent is his ability to make us believe in the characters he plays. He’s wonderful as the Pope in the Moretti film – the film has its strengths and weaknesses, but he is great. And in La Belle Noiseuse there are whole passages of the film where we see him looking at the model and not saying anything – it’s not him painting, and it’s not his hand we see – but he’s utterly engrossing. That’s one of the most persuasive portraits of an artist struggling to regain his creativity that I’ve seen. And again, it’s an extremely quiet performance. There’s never any hyperbole or rhetoric in his work.

As we’ve established, Piccoli worked with many of the greatest directors of all time, including Alfred Hitchcock, multiple films with Marco Ferreri, Michel Deville, and Manoel de Oliveira, as well as almost all the important French New Wave directors. I wondered if you had a particular favourite performance or performances by him?

There are so many. He is one of my favourite actors. Like Cary Grant, he’s someone that the camera loves in a way. I’ve always found that whatever is happening on screen my gaze is drawn towards Piccoli, the same way it is with Isabelle Huppert. They’re such interesting screen presences. Even though they’re not big roles, I love the two performances in the Demy musicals. I mean they’re different from one another but they’re great. He’s very funny in Diary of a Chambermaid. You know, terribly predatory in his sort of entitled lechery, and at the same time a pathetic figure because he can’t stand up to his wife, and he’s clearly terrified of her. There are so many delightful roles.

|

Piccoli in Hitchcock's Topaz (1969) |

Now that he’s passed away and we can look back with some distance at his extraordinary career, what kind of legacy, in your view, has Piccoli left us, and how important and influential would you say he was as an actor?

It’s difficult to say. I mean, one reason that I wanted to put on this season is my feeling that perhaps he’s not as well-known now as he should be, and that’s partly the passing of time and the fact that a lot of his biggest roles and most famous roles really were in the 60s and 70s. He did carry on after that, of course, and was hugely prolific. Certainly in France and Europe he was very highly thought of. But I think here he’s no longer as well-known as he should be. He spoke perfectly well in English, but he didn’t do very much English language cinema. He made a film with Basil Dearden early on, and he did Topaz with Hitchcock, though it's not a very good Hitchcock film. He also appears in Louis Malle’s Atlantic City. But I think he thought the sort of cinema he wanted to make, which, when I say serious, it doesn’t mean it can’t be comic – but serious films which are works of art, for want of a better word, which have aesthetic, and ethical, and political assumptions – those seem to be the sort of films he wanted to make – and that was always going to be much more available to him in France and Europe than it would have been in America or Britain. So, he’s not really as well known here as he should be, because he stayed in his own country. He certainly was very well known in the 60s and 70s, and cinephiles still know him, but I’ve got a feeling that he isn’t as well known here as he deserves to be. That’s the reason why I wanted to do the season, because he really was a major figure in European cinema for half a century.

Interview by Simon Hitchman, © May 2023 - please do not reprint or reuse without permission. |