film trailer

Why it’s important?

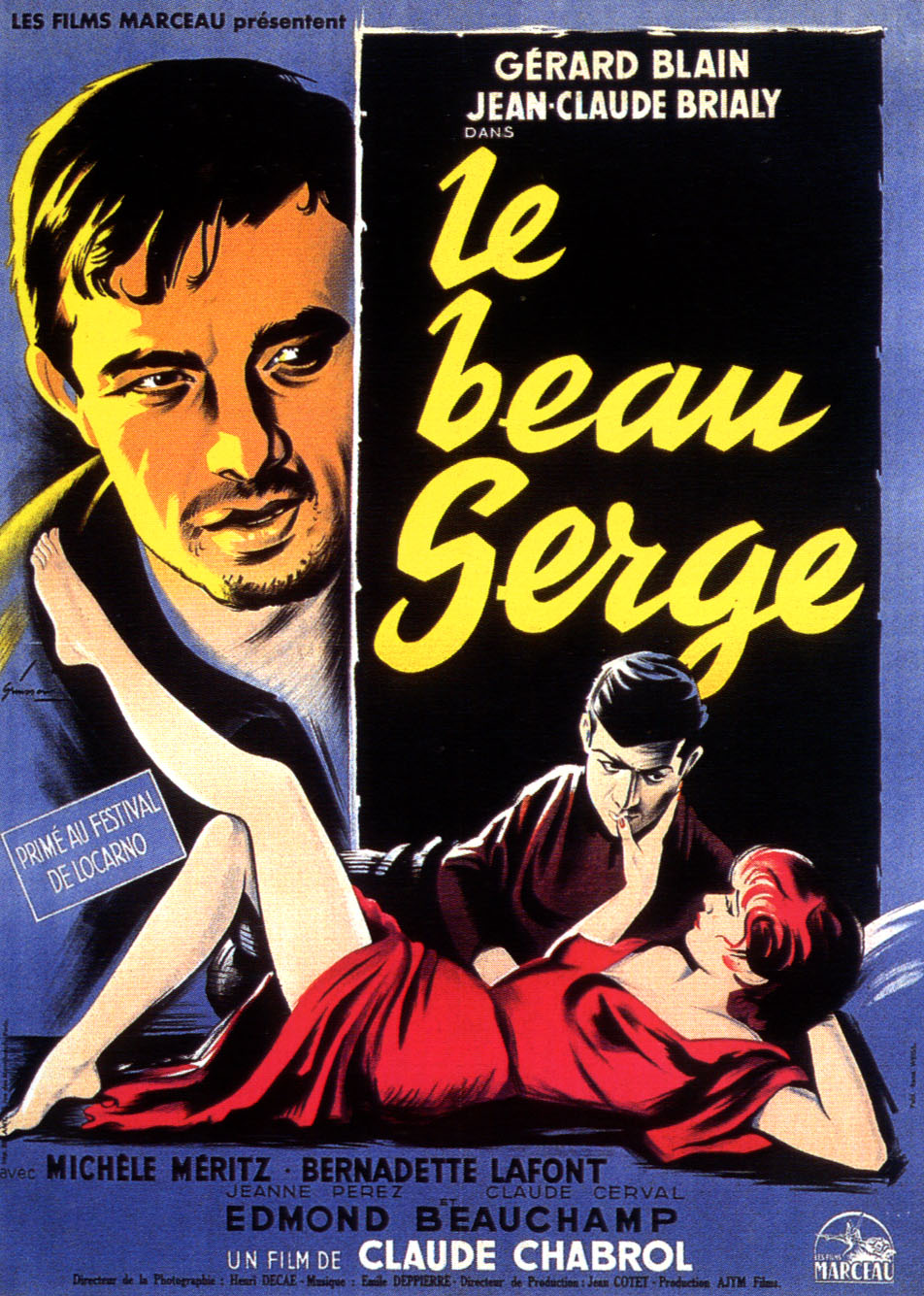

Le Beau Serge, directed by Claude Chabrol, has traditionally been cited as the first French New Wave film. While this assertion is contentious and ultimately un-provable, it is true that Le Beau Serge – shot in the winter of 1957/58, and shown to audiences for the first time at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival – was the first feature film to be released by one of the core group of five Cahiers du cinéma critics-turned-filmmakers (the other four being Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut) whose work would come to define the movement.

Whether it was the first New Wave film or not, the Le Beau Serge does exemplify many of the qualities that would come to be associated with the French New Wave: the story focuses on the travails of youth; it was shot on location using real locations and natural light; Chabrol drew on his own life for source material.

In making the film, Chabrol also demonstrated the spirit of collaboration for which the New Wave would become known in its early years. He brought in Charles Bitsch, Claude de Givray and Philippe de Broca as assistant directors (all would go on to careers of their own in the French film industry). And with the profits he made from the film (and its successor Les Cousins, 1959) he formed his own production company AJYM Productions, through which he was able to help fund the films of his friends, including the early work of Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette.

Le Beau Serge provided a showcase for a new generation of young actors. Before starring in the film, Jean-Claude Brialy had been a ubiquitous presence in the early Cahiers group's short films including Jacques Rivette's Le Coup du berger (Fools Mate, 1956), Jean-Luc Godard's Tous les garçons s'appellent Patrick (All the Boys Are Called Patrick, 1957) and the Truffaut/Godard co-production Une histoire d’eau (A Story of Water, 1958). Likewise, Gérard Blain and Bernadette Lafont had taken the lead roles in Truffaut's breakthrough short Les Mistons (1957). It was the success of Le Beau Serge, however, that confirmed the talent of these three actors, all of whom would go on to high-profile careers in French cinema.

The critical acclaim and commercial success of Le Beau Serge, not only launched Chabrol’s long and distinguished career, but also provided an inspiring example for others to follow. Though he had no formal qualification and had never directed a film before, Chabrol, working with a limited budget, succeeded in producing a technically adept feature film with a coherent thematic vision. His pioneering financing and production initiatives also set a precedent that others would follow.

Production Notes

Chabrol drew on his own life for Le Beau Serge. The story takes place in his hometown of Sardent. Like François, Chabrol had left the town while young to go to Paris to study (his return to make the film parallels François’ return). Like Serge and Yvonne, he and his wife had also experienced the personal tragedy of losing a child at birth.

Chabrol originally wrote the screenplay in response to an initiative set up by Italian director Roberto Rossellini who had came to Paris in 1957 intending to produce some 16mm films by young, first-time French directors. Chabrol thought the Catholic symbolism in his story would appeal to Rossellini, but the Italian director didn’t like the script and rejected it.

The same year Chabrol’s wife, Agnès, inherited a large sum of money from her grandmother. With her encouragement, he resolved to use this windfall to finance his directorial debut.

Initially, he wanted make what would be his second film, Les Cousins. However, realising that filming in Paris would cost too much, he decided that filming Le Beau Serge in the quiet rural village of Sardent would be more manageable.

There was also the problem of obtaining a professional director’s card from the Centre National de la Cinématographie (CNC), then an obligatory requirement in France for anyone wanting to direct a feature film. As Chabrol was producing the film through his own production company (AJYM Films), he was effectively his own boss, and therefore able to get around the rule. He also appealed to the CNC under the new prime de qualité rules to allow him to eliminate three union positions from the crew – set designer, sound engineer, and make-up person – in order to keep his costs down. The CNC agreed, thus setting a precedent that Truffaut, Godard, and others would follow on their first films.

Le Beau Serge was shot over nine weeks in the winter of 1957-8 on a budget of 32 million francs (the average cost of a mainstream French feature film at this time was approximately four times this figure). The crew included cinematographer Henri Decae, who had worked with Jean-Pierre Melville and Louis Malle, and was known to be inventive when it came to working on location using natural light. Chabrol also brought along three friends – Charles L. Bitsch, Philippe de Broca, and Claude de Givray – to work as assistant directors.

Many years later, Chabrol gave a self-deprecating account of the film’s production:

"For the record, I have to admit that during the first few days of Le Beau Serge, my first film, I was a real pain in the ass… I made everything very, very complicated because I still didn’t know cinematographic grammar… And I had a hard time finding the viewfinder on the camera! To the degree that in five days’ time very little was filmed save for a tracking shot of Brialy crossing the street, all happy at returning to the village he grew up in. This shot was successful and naturally elegant. Charles Bitsch, one of my three assistants on the film, with Philippe de Broca and Claude de Givray, took me aside to tell me that we were heading for disaster. And that, even if I was the producer, we’d have to stop because we’d end up running out of money. Relative to other directors of this era, like Allégret or Ciampi, who made movies for 120 to 130 million francs, I had somewhere around a quarter of that amount. We also had to reckon with the weather, the winter, the snowfall – which we needed for the end of the story when Paul and Serge cross Sardent at night for the childbirth… I think that even Terence Malick is an amateur next to Chabrol the beginner.”

According to Claude de Givray, the greatest source of tension on set resulted from Gérard Blain’s jealous feelings towards his co-star, and then wife, Bernadette Lafont. When a group of journalists came to the set, it was the flirtatious Lafont who became the focus of their story and their cameras, rather than the actor playing the title role. Things became even more fraught when Lafont began an affair with assistant Charles Bitsch. Blain realised something was going on and it became such a problem that Chabrol had to step in and tell Bitsch to leave the set and return to Paris. Soon after Lafont began another dalliance with Philippe de Broca, leading to a fistfight between the two men. Despite these difficulties, Chabrol managed to keep the production on track. His preparation was meticulous, and his directing style, according to witnesses, was gentle but with a natural authority.

Filming was completed in early February 1958, after which Chabrol returned to Paris to begin two months of editing with Jacques Gaillard. The first cut ran to 2 hours and 35 minutes and included substantially more documentary-like material of Sardent. Chabrol was prevailed upon to cut the film down to its eventual running time of 99 mins as he recalled in an interview for Movie magazine in 1963:

"At the outset, the film was at least two and a half hours long. Luckily I showed it to some people and they said, “Aie, aie!’ So I cut three quarters of an hour. And in comparison with the original scenerio I’d already cut half an hour. So it could have lasted three hours. It was cut mainly in the transitions, and then there were two things which took up a hell of a lot of time. The cutting was done so that the film could be more successful commercially, but I took care to make sure that the topography of the village was respected. So in order to get from one place to another, even if it meant going right across the village, one went right across following the guy or whoever it might be. That took plenty of time!"

After the Le Beau Serge was finished, Chabrol submitted it to the Film Aid Board and was granted a prime de qualité financial award of approximately the same amount as the 32 million francs it had cost to make the film. He therefore made back the film’s cost before it was released to the public, thus making it possible for him to start work immediately on Les Cousins.

Reception

Le Beau Serge had its premiere at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival. Francois Truffaut wrote a laudatory review for Cahiers du cinéma:

"Everyone agreed that the best film shown outside the festival was Claude Chabrol's Le Beau Serge. It was withdrawn here (from the main competition line-up) at the last moment by the "protectors" of L'Eau vive (The Water is Alive, Francois Villiers, 1958). (Chabrol's) film starts with psychology and ends with metaphysics. It's a chess game played by two men: Gerard Blain has the black pieces, and Jean-Claude Brialy the white. At the moment they meet, they change colours and the game ends in a tie. My interpretation may make this seem a purely intellectual work. But that is not the case. Le Beau Serge makes its impact through the reality of the peasant environment (the action takes place in Sardent, Creuse) and of its characters. In the role of Serge, Gerard Blain gives his best performance, and Jean-Claude Brialy, in a very difficult role, shows his dramatic gifts. Technically the film is as masterful as if Chabrol had been directing for ten years, though this is his first contact with a camera. Here is an unusual and courageous film that will raise the level of French cinema this year."

The publicity generated by the Cannes première and the favourable reviews Le Beau Serge received helped Chabrol find a domestic and foreign distributor. Their advances, combined with the money Chabrol had been granted by the Film Aid Board, enabled him to immediately begin shooting Les Cousins, thus keeping the momentum of his career going.

In August 1958, the film played in competition at Switzerland's Locarno Film Festival where it won the Award for Best Direction. Chabrol was also awarded the 1959 Prix Jean Vigo by the French Cinema establishment in recognition of the originality of his debut film.

Though only a modest financial success at the French box office, Le Beau Serge established Chabrol’s name as the figurehead of a new generation of French filmmakers who were soon to be dubbed "La Nouvelle Vague".

Themes & Analysis

The transposition of appearances

Chabrol wrote an article shortly after Le Beau Serge was released, entitled Flesh, Air, and the Subconscious, in which he expounded upon the film’s key theme:

"Here’s the theme: to encounter, in the very narrow framework that a poor country region presents, two kinds of young men: exact opposites, yet friends nonetheless. If I denied myself the artifice of physical non-resemblance, I forced myself to push to the maximum moral and social oppositions of the two. Pictorially, Serge’s universe is characterised by dark tonalities; François’s universe by light tonalities. But whereas Serge stands out in relief with lighter clothing against this dark background, François is the one more often dressed in dark hues. This, to illustrate one element of the film that struck me as very important: let’s say, the single one: the transposition of appearances. Indeed it appears, in the opening sequences, that Serge is an unstable person, tormented, complex – and burdened with complexes – while François seems all of a piece, even a bit uptight. Thus, the dramatic graphic arrangement of the film would seem to require the following: a straight line, corresponding to the character of François on top of which is superimposed the rougher edges of the Serge character.

But all the twists and turns of the film, to which I lent some colouration (very dear to me) of melodrama, aim to modify the structure of this dramatic line as though, once the problem was posed, the search for its solution radically modified the principle even of the given information. Indeed, beyond all appearances, a kind of truth must emerge for the spectator, little by little: the unstable one, the neurotic one, the crazy one, isn’t Serge, but Francois. Serge knows himself: he knows the why and the wherefore of his behaviour; he’s running away from himself. François, to the complete contrary, knows himself only as far as the level of appearances: his intimate nature is buried in his subconscious and only reveals itself in the harshest light; he’s running away from himself. His sickness has instilled within him a psychosis: the fear of dying, and as with all young people haunted by death, this psychosis translates itself into Christ-complex. I created, in François, – and without his being able to admit it to himself, and without his being expressed in any way other than through the nuances of his comportment – a latent homosexual, longing to return to a childlike state.

So the film’s denouement is two-fold. I set it in an atmosphere in which the two contrasting colours paradoxically come together as one: a snowy night. It seems that François saves Serge here from his downward spiral – and this is not incorrect. But François himself is, at the same time, saved from his madness by Serge who has taught him to shake up the truth of things.

Essentially, in Le Beau Serge two films are juxtaposed against each other: one in which Serge is the subject and François the object; the other in which François is the subject, Serge the object. By definition, it’s the first of these films which initially reveals itself. The ideal, for me, is that the other gradually be felt too."

Disillusioned youth

In common with many New Wave films, Le Beau Serge’s story focuses on contemporary youth and the disenchantment they feel about their lives. Serge, we learn, wanted to be an architect. He won scholarships and passed exams. However things did not go according to plan. He married Yvonne and stayed in Sardent. Their first child was born disabled and died soon after birth, leaving Serge angry and bitter. Now stuck in a dead-end job with few prospects, he spends his days in a drunken haze. François may have escaped the village, but his life too has gone adrift. Illness has cut short his studies and brought him home seeking refuge. We learn, through his conversation with the local priest, that he too once wanted to be a priest or a teacher. But now he appears to have little ambition other than to "earn lots of money". By contrast, their childhood contemporary Michel, is happy, admitting, "I always knew I’d spend my life here as a baker. I had no illusions".

Redemption

In his attempt to "save" Serge, François appears to regain a sense of purpose, though, at first, these attempts are unsuccessful. Indeed, his presence in the village only seems to exacerbate Serge’s discontent, causing him to drink even more. François pushes Serge to leave Yvonne, even though it becomes clear that she is the only person in the town who really cares about him. Eventually Serge lashes out, beating Francois up at the town dance while the unsympathetic villagers look on. Battered and bleeding, François returns to his hotel where even the landlady suggests he should leave town.

But François does not leave. For the next two weeks he stays in his room, refusing to see anybody. Eventually he agrees to see the priest, but their conversation ends in an argument.

Ironically it is Yvonne, who he meets outside gathering wood, who now becomes his closest ally and confidant. Soon after, when she goes into labour alone one wintry night, she sends for him. Despite his fragile health, François battles through the snow to find a doctor and to bring back Serge. This act of self-sacrifice is the act of redemption he has been seeking.

Chabrol underlines the religious dimension through Christian symbolism as at each stage of the journey François is encounters crosses: the window frame at Glomaud’s house where he finds the doctor, the fence by the hen-house where he eventually finds Serge in an alcoholic stupor, the door and window frames of Yvonne’s house where he drags Serge in time for the birth. Having finally accomplished his task, he collapses with the words, ‘I believed’.

At least one critic has speculated that François’ noble sacrifice in Le Beau Serge’s final sequence is nothing more than wishful thinking. That having retreated to his room, François is merely dreaming of how he would like things to work out. Chabrol himself never said anything to confirm this view, but it is certainly an intriguing interpretation of the change of tone in the final act of the film. Chabrol himself later regretted his use of symbolism, commenting in an interview: ‘It completely de-Christianised me. I had loaded the film with stupid symbolism. I had to, in order to rid myself of it all. Now, that’s all over with.’

Style

Chabrol and cinematographer Henri Decae capture Sardent in documentary-like detail. Their decision to film on location using natural light and real locations lends the film a rough edged authenticity reminiscent of Italian neo-realism. This led some at the time to assume that the film heralded the start of a new French strand of neo-realism. Closer examination, however, would suggest Le Beau Serge represents an ambitious – if not always convincing – synthesis of elements, incorporating Italian neo-realism, classical French cinema, and the work of Hollywood auteurs such as Nicholas Ray (Rebel Without a Cause) and Alfred Hitchcock (Shadow of a Doubt).

As a critic Chabrol had championed the films of Alfred Hitchcock (in 1957 he co-write the first serious book-length study of the director’s work with Eric Rohmer). Demonstrating what he had learned from the master, Chabrol uses cinematic language to delineate character and emphasize the underlying contrast between the smartly-dressed, well-mannered and middle-class François and the shabby, drunken, working-class Serge. As the film continues, however, it becomes apparent that the two men are more alike than they at first appear: both had youthful ambitions that have been thwarted; both have an older counterpart who represents what they might become (the Priest in François’ case, and the degenerate Glomaud in Serge’s); both have an affair with Marie (Serge in the past, François in the present). They are, in a sense, a mirror image of each other.

The theme of ‘the double’ is further highlighted by the underlying patterning of scenes. There are two scenes between François and the priest; two scenes in the cemetery – one featuring Serge, one featuring François; two close up shots of Serge with a fire burning behind him; two scenes between François and Marie at Glomaud’s house; two scenes in which Serge awakens from a drunken stupor – the first when Yvonne throws cold water in his face, the second when François rubs snow in his face; and two scenes of violence – when François beats up Glomaud, and when Serge beats up François. Such precise use of visual imagery would become a hallmark of Chabrol’s style throughout his career.

Key moments

After the opening credits, François arrives by bus in the village square. While he waits for his cases to be unloaded, the camera, mounted on top of the bus, pans abruptly to one side to reveal Serge and his father-in-law Glomaud. An ominous blast of music underlines the threat they pose to the newcomer.

The morning after returning to the village, François sets off to find Serge. In a moment of carefree insouciance he runs down the hill, a high-spirited boy once more. It’s a brief lyrical interlude in an otherwise downbeat film, anticipating in its youthful energy and virtuoso cinematography the nascent New Wave about to be born.

The presence of laughing children in the village are a haunting reminder of the carefree childhood Serge and François have left behind. In one particularly resonant scene, a group of boys are playing football in the town square as Serge lies against the war memorial in a drunken stupor. Disturbed by the noise, especially when one of the boys calls the other "François", he lurches to his feet and chases them away up the street. Though still a young man, Serge has now become the town drunk; an ogre feared by children.

In a sober and more affable mood, Serge walks with François to the edge of town where they stand beside a stagnant pond – clearly a metaphor for the listless inhabitants of the village. Here François suggests to Serge that he should leave Yvonne. Serge vehemently rejects the idea, assuring François that he loves his wife. It’s a side to him we have not seen before and contradicts the earlier impression his callous behaviour towards Yvonne may have given.

François’ return to the village has unforeseen, and not always welcome, consequences. While eating lunch in the boarding house where he is staying, he is confronted by the degenerate drunk Glomaud. Goaded by his insinuations, François tells Glomaud what everyone in the village already seems to know – that Marie is not his daughter. Thus, inadvertently, he provides the old man with the justification he’s been waiting for to go away and rape Marie.

After chasing down and beating up Glomaud, François returns to his hotel room. Gazing down from his window at the villagers below, he asks Serge: "Why are you like this? You're like animals. It's like you have nothing to live for. No purpose." Now it is Francois who appears callous and insensitive, and it is Serge who seems more humane, as he defends the villagers who 'earn barely enough to live on,' and the schoolchildren who have to walk three miles to get home each day "up to their knees in snow."

After Serge beats him up at the village dance, François staggers back to his boarding house and leans his head against a door. Over a close-up of François’ bruised and bleeding face there is a superimposed shot of falling snow. This haunting image evokes both the bleakness of François’ state of mind and of time passing. It might also suggest, as at least one critic has theorized, a shift from objective reality to a subjective dream state.

François spends the next two weeks holed up in his room contemplating his next move. After rejecting the priest’s advice to leave, François goes outside and meets Yvonne gathering firewood. He admits to her that he was wrong to blame her for Serge’s problems and they make peace with one another at last.

At the conclusion of the gruelling final sequence, François collapses against a wall in Serge’s house, murmuring under his breath, "I believed." Serge, hearing the cries of his baby, laughs with hysterical joy. Though ambiguous, the ending would suggest that faith has prevailed and François’ belief that he could save Serge has been vindicated.

Look out for

Chabrol appears briefly as La Truffe (who "has come in to some money"), alongside assistant director Philippe de Broca, who plays a character called "Jacques Rivette".

Where to go from here

Chabrol’s second feature Les Cousins (1958) is a mirror image of his first, and it’s fascinating to compare the two films. This time, reversing the good guy/bad guy roles of the earlier film, it is Gérard Blain who plays the naïve student who, in another reversal, travels from the country to Paris to stay at the apartment of his urbane cousin played by Jean-Claude Brialy. Out of his depth, the outsider finds himself drawn into a dangerous game of sexual obsession and excess.

For further cinematic depictions of small town life in rural France, look no further than Chabrol’s later masterpiece, Le Boucher (1970). Other notable examples include Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Le Corbeau (The Crow, 1943) and Robert Bresson’s Journal d’un curé de campagne (Diary of a Country Priest, 1951).

all rights reserved, all content copyright 2008-2025

|