ALAIN JESSUA SHOP & BOOKSHELF

|

|

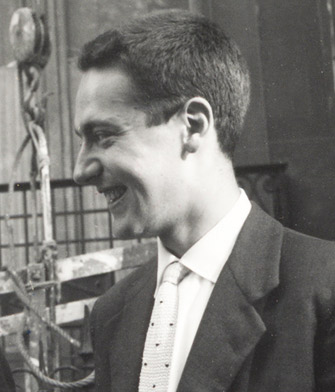

Alain Jessua ( 16 January 1932 - 30 November 2017) made an impressive start as a director, winning the Prix Jean Vigo award for his short film Lion la Lune (Leo Moon, 1956), and critical acclaim for his first feature La Vie à l’envers (Life Upside Down, 1964).His later films include the Cannes-award-winning Jeu de Massacre (The Killing Game, 1967), Traitment du Choc (Shock Treatment, 1973), Les Chiens (The Dogs, 1979) and Paradis pour tous (Paradise For All, 1982). Though relatively unknown today, his work is amongst the most imaginative and thought-provoking of its time. |

|

|

Dir. Alain Jessua

|

|

Early Life

Born in Paris in 1932 to a Jewish family, Alain Jessua spent World War II in hiding, an experience that left him with a lifelong sympathy with the plight of the outsider. He became fascinated by cinema and from a young age decided that he would become a filmmaker himself. After school he gained a valuable apprenticeship working as an assistant to directors Jacques Becker and Max Ophuls, from whom he learnt techniques that he would later use throughout his own career. In 1956, funded by a compensation pay-out following a car accident, he directed his first film: a short documentary about a day and night in the life of a tramp in the poetic realist style called Léon la lune (Leon the Moon). It earned him immediate recognition, winning the prestigious Prix Jean Vigo in 1957 and garnering the praise of the poet and screenwriter Jacques Prévert. Still only in his early twenties, Jessua’s career seemed set on a glittering course.

La Vie à l’envers

In fact seven years would pass before Alain Jessua made his next film. In that time the Nouvelle Vague came to prominence, making it possible for an unprecedented number of unknown directors to break into the industry. Though he never felt closely affiliated with the movement, Jessua was of the same generation as its leading figures and shared with them a passion for cinema and an uncompromising determination to follow his own path. Most of those who followed in the New Wave’s wake would soon be forgotten, but the brilliance of Jessua’s first feature-length film, La Vie à l’envers (Life Upside Down, 1964), was immediately apparent. This quietly terrifying “indoor suspense film”, tells the story of Jacques, a young estate agent played by Charles Denner, who asks himself the question that has preoccupied thinkers for centuries: What is the purpose of life? His answer is to turn his back on his outwardly successful existence and withdraw into a life of solitary contemplation. Is he inspired or mad or simply self-indulgent? Jessua leaves us to make up our own minds while drawing us subjectively into Jacques’s increasingly surreal perception of the world around him. Inevitably his behaviour alienates those around him and he loses his job, his friends, his new wife, and is finally locked up in an insane asylum. “I’ve won,” he chuckles to himself, happy to have exchanged his freedom for the opportunity to spend his days contemplating the blank walls of his hospital room. La Vie à l’envers won Jessua the Award for Best First Work at the 1964 Venice Film Festival and established him as a writer/director with an original cinematic vision as distinctive as any of his contemporaries.

Jeu de massacre

Jessua took his examination of madness to another level in his next film: Jeu de massacre (The Killing Game, 1967). This time the unbalanced mind belongs to a wealthy playboy called Bob (Michel Duchaussoy), whose desire to escape his sheltered life and emulate the exploits of his fictional heroes is fulfilled when he persuades Pierre and Jacqueline (Jean-Pierre Cassel and Claudine Auger), the creators of his favourite comic, to stay at his house and turn him into the hero of their newest adventure. When Bob identifies a little too closely with his alter ego and starts acting the stories out, he draws his house-guests ever deeper into his dangerous delusions. Faster-paced than Life Upside Down and shot in the vivid Pop Art colours of the comic strip created for the film by celebrated artist Guy Peelart, Jeu de massacre encapsulated the spirit of the 1960s in the characters of the idealistic/delusional Bob and the hedonistic/ cynical Pierre. Its qualities were recognised at the 1967 Cannes Film Festival where Jessua won the award for Best Original Screenplay, after which it went on to become a considerable box office hit in France.

Le Planet Bleu

Buoyed by success, Jessua began work on his dream project: a science-fiction film called Le Planet Bleu. The scale of the ambitious production required the backing of a producer with considerable clout, so when Carlo Ponti, the famous Italian producer behind numerous high-profile movies including Godard’s Les Mepris (Contempt, 1963) and David Lean’s Dr Zhivago (1965), showed an interest in the screenplay, it seemed like there was every chance it would go into production. This lead to what Jessua later described as his “living like a tramp in the lap of luxury for three years in London, Rome and New York” as Ponti funded development but failed to commit the large amount of money needed to make the film. Finally, realising that Ponti was lying to him, Jessua relocated to Los Angeles and tried to find financing for the film there, but now the New Hollywood era of low-budget, American-themed movies like Easy Rider was in full swing and the studios had scant interest in gambling on a big-budget science-fiction movie by an unproven European director. Disheartened, Jessua returned to France and checked himself into one of the then fashionable thelassotherapy (seawater therapy) spas in the hope of restoring his spirits. It was here that he first conceived of the idea for his next film.

Traitment du choc

Set in an exclusive health clinic whose rich clientele are there for rejuvenation treatments to make them feel and look younger, Traitement du choc (Shock Treatment, 1973) starred Alain Delon and Anne Girardot – then two of France’s biggest stars – as Doctor Devilers, the charismatic head of the establishment, and Hélène, a fashion designer who has come to the clinic feeling “old” after being ditched by her lover for a younger woman. At first pleased when the treatments apparently work, and seduced by the doctor’s charms, Hélène soon becomes disturbed by the mysterious suicide of her closest friend and the disappearance of some of the young Portuguese men working at the spa. Intent on investigating, she stumbles upon the terrible truth in the doctor’s laboratory.

Treading a fine line between suspense thriller and social satire, Traitement du choc today seems astonishingly prescient given the modern obsession with looking and feeling young at all costs. Its portrayal of a bourgeoisie ready to turn a blind eye to the exploitation of others as long as it suits their own selfish ends is as disturbing as anything cooked up by Bunuel or Chabrol. Jessua handles the genre elements with a deft hand: drawing us into the seductive lifestyle of the inhabitants of the resort and building suspense until the final horrifying climax. Characteristically, there’s no reassuring resolution, as Hélène discovers the fate of those who dare to take on the clinic and its clientele of the powerful elite.

Armaguedon

Traitement du choc was the first of four tautly plotted dramas Jessua made over a ten-year-period which drew on contemporary anxieties in the guise of what might be described as “cautionary tales”. Armaguedon (1977), adapted from the novel The Voice of Armageddon by David Lippincot, again starred Alain Delon, this time as a police psychologist hunting down a terrorist operating under the pseudonym of “Armaguedon”. Jean Yanne gives a powerful and moving performance as the one-man revolutionary Carrier, a nobody with meglomaniacal tendencies whose craving for recognition leads him down a desperate path. Although it occasionally gets bogged down in the not-entirely-plausible Interpol investigation, and Delon seems one-dimensional in the role of the psychiatrist (Michel Duchaussoy who plays the police inspector would have been a better, if less commercial, choice for the role), Armaguedon is a compelling and ultimately sympathetic study of alienation in modern society. The behaviour of the crowd during the climactic showdown – a suspense set-piece worthy of Hitchcock – only serves to underline everything Carrier has said in his broadcast about human nature, as the people laugh at his manifesto then trample each other to death in their rush to save their own skins.

Les Chiens

Equally pessimistic in its view of human nature, Jessua’s next film Les Chiens (The Dogs, 1979) occupies a similar conceptual and physical terrain as the stories British science-fiction author JG Ballard was writing at this time. Set in a bleakly modern provincial town where a series of unsolved attacks are spreading a climate of fear amongst the populace, it stars Gerard Depardieu as Morel, a dog-trainer with a philosophy of self-empowerment bordering on the Nietzschean, who appears to have the answer to the town’s problem. Tense and confrontational, the film very effectively shows how easily a stratified community can turn to fascism out of panic. Yet, remarkably, Jessua succeeds in drawing our sympathies for both sides in the hostility and introduces a ray of hope in the shape of a community of African refugees whose good humour and simple enjoyment of music offer some kind of alternative to the entrenched resentment felt elsewhere. Inevitably though violence leads to more violence and Morel ends up reaping the consequences of his ruthless ideology.

Paradis pour tous

The final and most ambitious of this loose quadrilogy, Paradis pour tous (Paradise For All, 1982), seems, at first, lighter in tone than its predecessors, though events in the story quickly take a disturbing turn. Patrick Dewear, an exceptional actor who tragically died soon after the film was made, plays Alain, a suicidal insurance agent who is cured of his depression by “flasage” – a new therapy invented by Dr Valois (Jacques Dutronc) – that aims to make people feel permanently happy. Unfortunately it also makes Alain completely indifferent to other’s pain and suffering. Always smiling, always serene, Alain and his fellow guinea pigs are a success in their new lives, although their lack of empathy damages their personal relationships. Alain’s wife Jeanne (Fanny Cottencon) is particularly disturbed by her husband’s dispassion about everything. Yet rather than attempt to reverse the process, Dr Valois decides the only answer is to “flasage” both Jeanne and himself. Inspired by Jessua’s time living in Los Angeles, Paradise for All is a darkly comic, sometimes grotesque, satire that brilliantly targets the unhealthy desire people have to be happy all the time, even when that desire robs them of their humanity.

Later work

In his next two films Jessua took a step back from the moral complexity of his earlier work into the realm of pure genre entertainment. Frankenstein 90 (1984) was a comedy update of the horror classic featuring Jean Rochefort as Victor, a direct descendent of the original Baron Frankenstein, who assembles body parts to create a new kind of human being. His creation, Frank, played with genuine pathos by rock and roll star turned actor Eddy Mitchell, means well but his desire for a mate leads to murder and mob reprisals. Following this, Jessua made En toute innocence (No Harm Intended, 1988) a psychological suspense thriller set in a country estate near Bordeaux, starring Michel Serrault as a wealthy architect who catches his daughter-in-law (Nathalie Baye) in an act of adultery immediately before crashing his car. He is left with broken legs and an apparent loss of speech. An escalating cat-and-mouse battle of wills then ensues as the two vie for dominance over the household. Serrault and Baye are, as you might expect, a pleasure to watch as they attempt to outmanoeuvre each other, revealing as they do so the resentment and disillusionment concealed beneath the calm exterior of bourgeois life.

Almost a decade passed before Jessua made Les Couleurs du Diable (The Colors of the Devil, 1997), a modern retelling of the Faust legend in which a young painter, Nicolas (Wadeck Stanczak), accepts the help of a mysterious stranger, Bellisle (Ruggero Raimondi), who promises to provide him with the inspiration that will bring him success. In his case this means bringing him face to face with real life experiences of death; a tactic that works as Nicolas’s morbid paintings of what he has seen attract a following and bring him great success. Sadly, despite its promising premise, Les Couleurs du Diable proved a frustrating experience for Jessua who felt he did not have the budget he needed to make the most of the material. Following its failure, he gave up filmmaking. In the years since he has instead turned his storytelling skills to the writing of novels whose titles include Crèvecoeur (1999), Ce sourire-là (2003), Bref séjour parmi les hommes (2006), La Vie à l’envers (2007) – a novelisation of the film, Un jardin au paradis (2008) and Petit ange (2011).

Personal Life

Alain Jessua was married for some years to the actress Anna Gaylor who appeared in a number of his films. They had one child. He died in Paris on the 30th November 2017 at the age of 85.

French Title |

English Title |

Year |

Category |

Notes |

| Léon la lune |

|

1956 |

short |

|

| La vie à l'envers |

Life Upside Down |

1964 |

feature |

|

| Jeu de massacre |

The Killing Game |

1967 |

feature |

|

| Traitement de choc |

Shock Treatment |

1973 |

feature |

|

| Armaguedon |

Armegeddon |

1977 |

feature |

|

| Les Chiens |

The Dogs |

1979 |

feature |

|

| Paradis pour tous |

Paradise for All |

1982 |

feature |

|

| Frankenstein 90 |

|

1984 |

feature |

|

| En toute innocence |

No Harm Intended |

1988 |

feature |

|

| Les Couleurs du diable |

The Colors of the Devil |

1997 |

feature |

|

|