What is American New Wave?

The term “American New Wave” has been used to refer to at least three generations of American filmmakers. The first, emerging in the 1950s in New York, were concerned with realism and a truthful depiction of American society at the time.

The second, often called the New Hollywood Generation, rose to prominence in the late 60s, bringing a new set of values representative of the counter-culture and an aesthetic influenced by the French New Wave. More recently, in the late 80s and 90s, a new generation of filmmakers working outside the studio system and openly in debt to both the Nouvelle Vague and New Hollywood were awarded the mantle. What all these filmmakers shared in common was a desire to work independently of studio control and a belief in cinema as an art rather than mere entertainment.

Birth of the Independents

D.W. Griffith, Mary Pickford, Douglas Faribanks, and Charlie

Chaplin at the beginning of United Artists. [1919]

|

There had been filmmakers working independently of the major production companies since the earliest days of cinema in America. In 1919 four of the leading figures in American silent cinema (Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and D.W. Griffith) formed United Artists, the first independent studio. Their aim was to better control their own work as well as their futures. Other important filmmakers, including the father of documentary Robert Flaherty, the visionary King Vidor, and other lesser-known figures also produced films independently.

Following World War II, the efforts of a body known as The Society of Independent Motion Picture Producers limited the power of the major studios to control film distribution and exhibition, thereby allowing smaller, independent producers a chance to compete. This, combined with the advent of less expensive, portable cameras, made it possible for independent filmmakers to make films without the backing of a major studio.

Among the first to take advantage of the new possibilities were fiercely original avant-garde filmmakers such as Maya Deren and Kenneth Anger whose surreal 16mm short films like Meshes of the Afternoon and Fireworks would inspire some of the leading directors of New Hollywood cinema. Documentary directors like Flaherty (Louisiana Story) and Sidney Meyers (The Quiet One) also produced award-winning work independently.

Auteurs and Mavericks

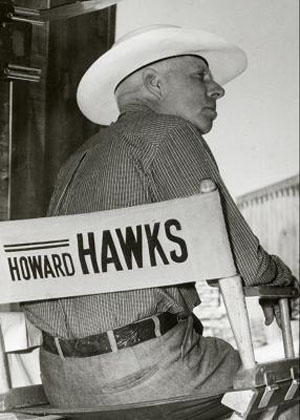

Director Howard Hawks

|

During Hollywood’s Golden Age – roughly 1930 to 1960 – most leading film directors made their films for one of the Major studios (MGM, Paramount, 20th Century-Fox, Warner Bros., RKO, United Artists, Columbia and Universal). Despite being part of an industrial

process whose purpose was to make entertainment for the masses, many of these directors, including John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles, retained a distinct artistic vision and thematic consistency in their work. French critics writing for Cahiers du Cinema were the first to recognise these Hollywood directors as artists with their own personal creative visions who were the true "auteurs" or the authors of their films. By uncovering the complex depths in the work of directors who had previously been thought of as simply excellent craftsmen, the young writers broke new ground, not only in the way a film was understood, but also in how cinema itself was perceived. Their theories would have a big impact on later generations of American directors.

Some notable American directors worked outside the Hollywood Studios for small independent producers. One of the most celebrated of these was Samuel Fuller who

began his career as a screenwriter in the 1930s. He made his break into directing in 1949 with I Shot Jesse

Samuel Fuller's Pickup on South Street [1953]

|

James, subsequently carving out an uncompromising path as a genre director with a uniquely personal, and often politically controversial, vision. Another was actress Ida Lupino who formed an independent production company with her husband Collier Young, becoming a producer, director and screenwriter of low-budget, issue-oriented films and film noirs. Other influential directors who made their names working in independently produced film noirs were Stanley Kubrick and Robert Aldritch.

Exploitation movies offered independent producers the potential to make money outside the mainstream. One of the most successful was Roger Corman whose prolific output of low-budget B movies from the mid-1950s onwards included such cult classics as A Bucket of Blood (1959) and Little Shop of Horrors (1960). He achieved his greatest artistic success with a series of Edgar Allen Poe adaptations beginning with The Fall of the House of Usher (1960). Other celebrated independent exploitation filmmakers who helped define their genres at this time included Russ Meyer (sexploitation) and Herschell Gordon Lewis (horror).

The First American New Wave

Far from the glamour of Hollywood, 1950s and 60s New York provided the crucible for a loose assortment of filmmakers who between them helped give birth to modern independent American cinema. These filmmakers were more concerned with capturing the human drama of everyday life than sticking to established genres.

While roughly contemporaneous with the French New Wave movement, and sharing some of its characteristics and values, it was not directly influenced by it. Emerging, not from film criticism, but from acting, dance, photography, documentary and experimental cinema, their common denominators were a fidelity to realism, a focus on character above story, and the desire to explore social milieus normally overlooked by mainstream cinema and television.

Morris Engel's The Little Fugitive [1953]

|

If one wished to define the start of this movement there could no better place than with the charming and surprisingly successful Little Fugitive (1953). Made on a shoestring budget by still photographers Morris Engel, Ray Ashley and Ruth Orkin, the film tells the story of a 7 year old boy who runs away to Coney Island during the peak of the Summer holiday season and spends a day and a night alone amidst the hurly burly of the seaside resort. The film’s amusing and unsentimental depiction of childhood proved a hit with audiences and critics, winning two Academy Award nominations and the Silver Bear Award at the 1953 Venice Film Festival. It even influenced the French New Wave, with Francois Truffaut commenting years later: “Our New Wave would never have come into being if it hadn’t been for the young American Morris Engel, who showed us the way to independent production with this fine movie.” Engel made two more features, Lovers and Lollipops (1956) and Weddings and Babies (1960), all filmed with hand-held 35mm cameras.

Lionel Rogosin was a wealthy executive in his father’s textile business when he decided to make a documentary about the poverty near his Greenwich Village Home. Rogosin used his own money to produce and direct On the Bowery (1956), a neorealist view of New York’s skid row as seen through the eyes of three of its inhabitants over three days. Real homeless men play themselves in scenes both real and staged. The film, a powerful depiction of alcoholism and despair, won the Grand Prize for Documentary at the 1956 Venice Film Festival, the British Award for Best Documentary, and was nominated for an Oscar. The

Corso (hat), Larry Rivers, Kerouac, David Amram & Allen Ginsberg in Pull My Daisy [1959]

|

film had a major influence on other realist filmmakers including John Cassavetes who described Rogosin as “the greatest documentary filmmaker of all time.”

Another visionary turning his camera on the underbelly of America was Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank who spent two years between 1955 and 1957 travelling across America taking photographs of the real people he encountered along the way. The Americans, published in 1958 with an introduction by Beat writer Jack Kerouac, was a landmark in photography. Soon after Frank had moved away from photography to concentrate on filmmaking. His first film, Pull My Daisy (1959), co-directed with artist and filmmaker Alfred Leslie, was written and narrated by Kerouac and starred Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and other Beat personalities. Set in a New York apartment, it tells the story of a railway brakeman whose wife invites a bishop over for dinner, only for the brakeman’s bohemian friends to crash the party with inevitable comic results.

John Cassavetes

Combining the poignancy of The Little Fugitive, the authenticity of On the Bowery, and the jazzy vivacity of Pull My Daisy, John Cassavetes’ Shadows, released in 1959, was the emblematic cornerstone of the first American new wave. Filmed with a 16mm handheld camera on the streets of New York over two years with a cast made up mostly of actors from Cassavetes’ own method acting workshop, Shadows was innovative in every respect and a world away from the mainstream cinema of its time. Much of the dialogue was improvised as Cassavetes grasped for a new form to express new ideas. The narrative, concerning an interracial romance, was audacious in its own right, but Cassavetes places the emphasis on character rather than story, never judging his characters’ actions but observing them from the outside. The film was recognised as a major accomplishment by some perceptive American critics who heralded it as the vanguard of a new American cinematic revolution equivalent to what was happening in France. It also won acclaim at the 1960 Cannes Film Festival and at the Venice Film Festival where it won the Critics Award.

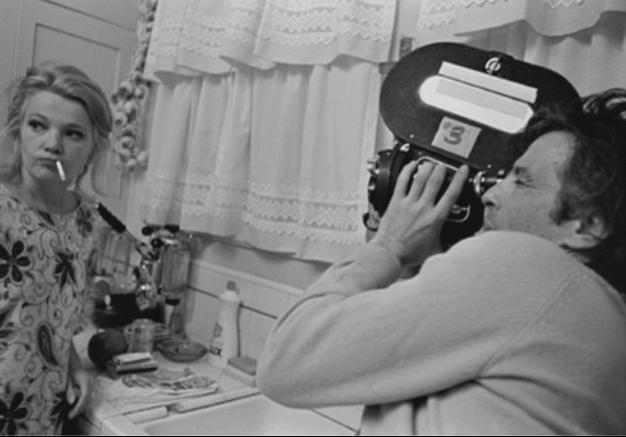

Cassavetes directing Faces [1968]

|

The film’s success brought Cassavetes to the attention of Paramount Studios who hired him to direct two films, Too Late Blues (1962) and A Child is Waiting (1963), both of which failed to impress either critics or public. Cassavetes returned to acting, appearing in such films as Don Siegel’s The Killers (1964), The Dirty Dozen (1967) and Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968). With the money he earned, Cassavetes was able to continue his passion for independent filmmaking with Faces (1968). Free of studio interference, the film’s portrait of a disintegrating middle-class marriage is an uncompromising study of the despair and emptiness at the heart of the American dream. Refining his trademark improvisational, cinema vérité style, Cassavetes’ raw and sometimes uncomfortable film confirmed the promise of Shadows. It was nominated for three Academy Awards and was a surprise box office success. In the years to come, John Cassavetes would continue his examination of the alienation of American life in such films as Woman Under the Influence (1974) and Lovestreams (1984), becoming the archetype of the uncompromising independent director and a hero and mentor to the New Hollywood generation.

Shirley Clarke

Director Shirley Clarke

|

Another leading figure of the New York New Wave was Shirley Clarke who began by filming dance performances in the mid-1950s, before turning her attention to abstract studies of architecture in Bridges Go-Round (1959) and the Academy Award nominee Skyscraper (1960). She came to wider public attention with The Connection (1961) about a group of jazz musician drug addicts waiting for their fix. Like Cassavetes’ Shadows, it was a landmark of its time, heralding an unflinching new cinematic realism focused on pressing social issues. The Cool World (1964), shot on the streets of Harlem and employing a cast from a mainly non-acting background, looked at street gangs, while Portrait of Jason (1967) was an unflinching documentary portrait of a black homosexual prostitute. Clarke’s groundbreaking films took risks in both content and form, foregrounding the filmmaking process and implicating the viewer in the events portrayed.

The New American Cinema Group

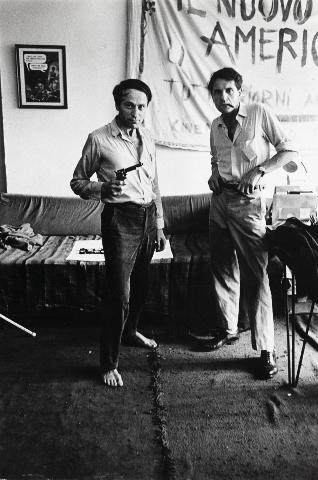

Jonas Mekas and his brother Adolfas in 1962

|

On September 28th, 1960, some 23 independent filmmakers lead by writer Jonas Mekas, and including Clarke and Stan Brakhage, issued the First Statement of the New American Cinema Group in Film Culture magazine in which they committed themselves to a cinema of “personal expression” in opposition to “the Product Film”, and rejecting “the interference of producers, distributors and investors”, while taking a stand against censorship and “the present distribution–exhibition policies.” They announced plans for grants, a festival and cooperative distribution center. In 1962 the Film-Makers’ Cooperative was formed, putting many of these aspirations into practice. Jonas Mekas also found time to make films himself including the story of a bohemian girl’s suicide in Guns of the Trees (1960), and an intense adaptation of Kenneth Brown’s play set in a military prison, The Brig (1964).

In his statement, Mekas refers to a new generation of filmmakers in other countries – Free Cinema in England, the Nouvelle Vague in France, the young movements in Poland, Italy, and Russia – with whom he aligns the New American Cinema. While the New York School may not have been as cohesive and defined a group as some of the other new wave movements, it is true to say they displayed many of the same ambitions and characteristics. Made up of a loose collection of avant-garde, theatrical and documentary filmmakers, they shared an antipathy toward mainstream cinema and the courage to pursue their own vision. As Mekas wrote in the conclusion of his statement: “we are for art, but not at the expense of life. We don’t want false, polished, slick films – we prefer them rough, unpolished, but alive; we don’t want rosy films – we want them the color of blood.” The example they set would have a profound influence on several generations of American filmmakers.

Return to: 'American New Wave' home.

|