1970 – 71

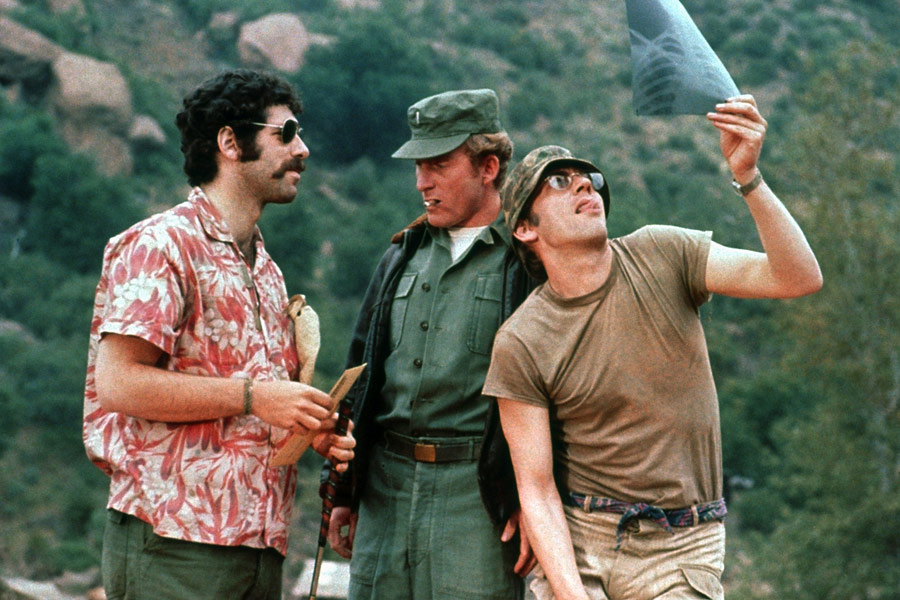

Dustin Hoffman in Little Big Man [1970], directed by Arthur Penn.

|

On July 21st 1969 Richard Nixon was inaugurated as the thirty-sixth president of the United States on the strength of a campaign pledge to end the war in Vietnam and bring the country together. Once in office, however, his strategy led to an escalation of the war leading to the invasion of Cambodia in the first months of 1970. This action unleashed a storm of protest across the nation, culminating in the killing of four college students at Kent State University by the Ohio National Guard on May 4th.

Although, by now, the American public had become used to seeing graphic newsreel footage of the conflict unfold on their television screens every night, very few people were yet ready for fictionalised renderings of the war. Filmmakers instead responded indirectly through revisionist Westerns such as Ralph Nelson’s Soldier Blue (1970) and Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man (1970), which portrayed the U.S. cavalry – traditionally seen as upholders of justice and decency – as bloodthirsty and cruel. Both films dramatised the notorious Sand Creek Massacre of 1864 when approximately 150 Indians, most of them women and children, were massacred by the U.S. cavalry. It didn’t take much imagination to equate this atrocity with the Mai Lai Massacre in1968 in which the U.S. army indiscriminately slaughtered as many as 500 men, women and children.

Hoping to encapsulate the anti-war mood of the time, Mike Nichols, then at the height of his fame after directing The Graduate (1967) and Neil Simon’s hit play Plaza Suite on Broadway, went into production on a big-budget adaptation of Joseph Heller’s celebrated absurdist World War II novel Catch-22. With its all-star cast, comic screenplay by Buck Henry and spectacular aerial sequences, the film should have been a hit but it failed to connect with either critics or audiences and was ultimately trumped by M*A*S*H (1970), a satirical black comedy directed by a then little-known director, Robert Altman.

"This isn’t a hospital! It’s an insane asylum"

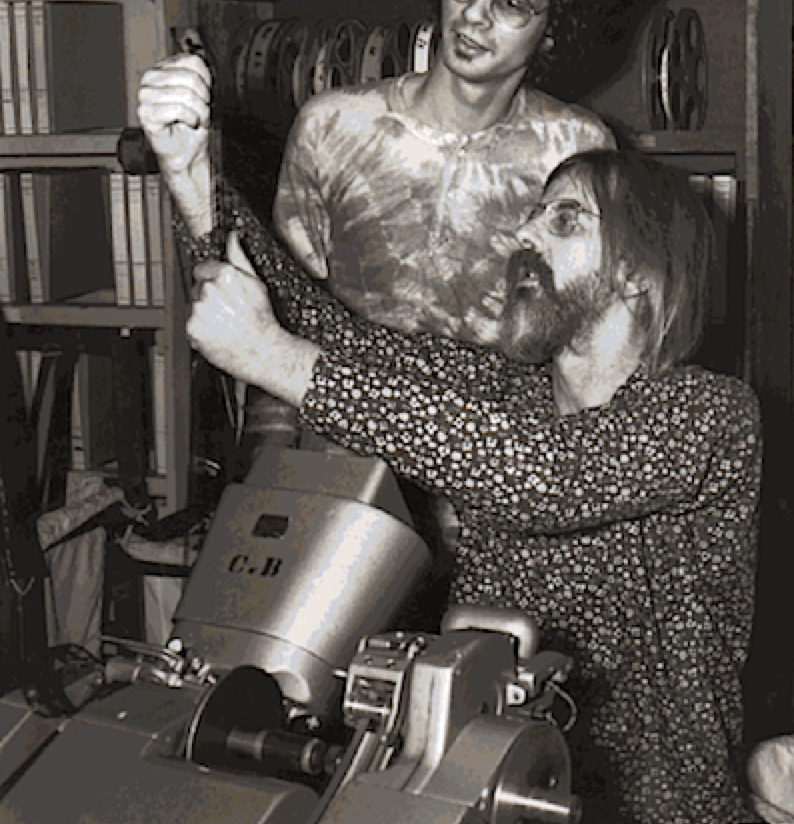

a young Robert Altman

|

Success had been a long time coming for Robert Altman. Born in 1925 to a well-to-do family in Kansas City, he served in the United States Air Force during World War II. After the war he spent time trying to make it as a writer before accepting a job with the Calvin Company for whom he directed some 65 industrial films and documentaries. In 1956 he was hired by a local businessman to write and direct a low-budget feature film in Kansas City on the subject of juvenile delinquency. The Delinquents, as the film was appropriately called, was sold to United Artists and soon afterwards Altman abandoned his hometown and family and moved to Los Angeles where he landed a job directing episodes of the television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents. This was followed by a decade’s worth of work in television in which he honed his craft and experimented with the narrative techniques and innovative methods that would later make him famous. At the same time he also gained a reputation as a hard-drinking, uncompromising character who invariably quarrelled with his employers.

Altman’s big break came one day in 1969 when his agent handed him a screenplay for a black comedy set in a military field hospital during the Korean War. Anti-war, anti-authoritarian and anti-religion, M*A*S*H, written by Ring Lardner, Jr., had been turned down by a lot of directors but Altman immediately saw its potential. Producer Ingo Preminger backed Altman to direct despite the misgivings of 20th Century Fox, the studio backing the film, who believed a deal with Altman spelt trouble. They agreed only on condition that the director work at a reduced rate with no percentage of any profits. Since his previous film That Cold Day in the Park (1969) had flopped at the box office, Altman had little choice but to agree.

Once on set, however, Altman was determined to do things his own way. M*A*S*H’s broad canvas and large ensemble cast provided the director with the perfect opportunity to experiment with widescreen composition, zoom lenses and overlapping sound and dialogue: techniques that would in time come to define the "Altman style". At this early stage his career, though, his unconventional, apparently casual approach to directing caused tension with both veteran members of the crew and the film’s stars, Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould, who tried to get Altman fired during production. Fortunately Preminger believed what Altman was doing was right for the picture and stood by him.

M*A*S*H [1970]

|

Ultimately Preminger’s faith proved to be justified as M*A*S*H became one of the biggest commercial and critical hits of 1970, winning the Palme d’Or at the 1970 Cannes Film Festival, the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture, and receiving five Academy Award nominations (it won for Best Screenplay). After years of struggle Altman had broken through, becoming not only a bankable director, but also a genuine auteur with a distinctive vision that would place him at the forefront of the New Hollywood.

Nobody was more surprised by M*A*S*H’s success than 20th Century Fox chief executives, Richard Zanuck and David Brown. They had originally planned to make extensive cuts to the film but the enthusiastic audience response at early test screenings changed their minds. The film went on to become the third highest grossing film of 1970 just behind the far more mainstream fare of Love Story and Airport. Warner Brothers were similarly surprised when Woodstock (1970), a low budget film about the music festival they’d originally been reluctant to back, grossed an astounding $16.4 million at the domestic box office. MGM fared less well with Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970): the Italian auteur’s attempt to evoke the spirit of youthful rebellion in late 60s America failed to connect with audiences in the way that Blow Up (1966) had a few years earlier. Audience tastes were clearly changing but never had they been so difficult to predict. As one studio executive later recalled: “Everything seemed different after Easy Rider. The executives were anxious, frightened because they didn’t have the answers any longer”.

“You know, this used to be a hell of a good country”

Jack Nicholson and Karen Black in Five Easy Pieces [1970]

|

Easy Rider’s producers, Bert Schneider and Bob Rafelson, were taking advantage of their enhanced status to build a new Hollywood powerbase. Along with their long-time friend and colleague, Steve Blauner, they formed BBS (Bert, Bob, and Steve) and agreed a deal with Columbia that allowed them to produce six films without interference as long as each cost under $1 million. Their company headquarters soon became the hippest spot in Hollywood where artistic and political radicals could hang out, watch the latest foreign art films, smoke a joint and exchange ideas.

BBS’s first production, the character-driven Five Easy Pieces, was a personal, semi-autobiographical project for its writer/director Rafelson that set the template for the company’s subsequent output. Co-written with Carole Eastman, the screenplay about a classically trained pianist who has given up his privileged background to work on an oil field and live a blue-collar life, was notable for its eloquent and often hilarious dialogue. One scene in particular – a confrontation between the main character Bobby Dupea character and a hostile waitress over a menu item – has since gone down in cinema history. On location cinematographer Lászlo Kovác’s camera captured, not only the foreground story, but also a then rarely recorded American backdrop of trailer parks, bowling alleys, diners and motels, while, in the lead role, Jack Nicholson’s complex, nuanced performance confirmed him as one of the greatest actors of his generation, ably supported by Lois Smith, Ralph Waite and Karen Black.

Despite its minimal plot, Five Easy Pieces was a major critical and commercial hit. By applying a European sensibility to distinctly American settings and themes, Rafelson had succeeded in forging a new kind of freewheeling national cinema whose disillusioned protagonists were chasing, or more likely retreating from, a tarnished American Dream. It was a model that would prove highly influential on other directors and help define the American cinema of the time.

The Last Movie

Dennis Hopper in The Last Movie [1971]

|

Meanwhile Easy Rider’s director Dennis Hopper was immersed in his own personal project. Set in a remote Peruvian village, The Last Movie focused on a cowboy stuntman working on a Western who remains behind after the production has wrapped, only to find himself drafted into an imaginary recreation of the movie made by the Indian villagers who previously witnessed it being shot. It was, conceptually at least, a fascinating exploration of, amongst other things, American colonialism and the disorienting effect of modern culture on those unprepared to receive it, yet Hopper struggled to find a studio willing to back the film. BBS, still raw from the experience of working with Hopper on Easy Rider, turned him down, as did Warner Brothers. Eventually Universal Pictures, which had set up its own low budget division headed by Ned Tanen to try to cash in on the youth market, agreed to back the project. Crucially for Hopper, he was given final cut as long as he didn’t go over budget.

Shot on location in Peru, mostly in the remote mountain village of Chinchero, The Last Movie starred Hopper in the lead role, supported by a cast that included Peter Fonda, Kris Kristofferson, Samuel Fuller and Michelle Phillips. Alcohol and drug abuse were rampant throughout the shoot and conditions so primitive that many of the crew got sick and had to return home. Mercurial as ever, Hopper managed, according to Kristofferson, to antagonize the Catholic Church, the ruling military junta, and the communists.

Returning with forty hours of footage to his ranch in Taos, New Mexico, Hopper spent the next sixteen months editing the picture together. The first cut had a mostly linear structure, but on the advice of the Chilean director Alejandro Jodorowsky, Hopper destroyed this version and crafted a more disjointed narrative. When the film finally premiered in 1971 it initially did well, winning the Critics Prize at the Venice Film Festival, but when the American reviews came out they were devastating. Roger Ebert described the film as “a wasteland of cinematic wreckage”, and Vincent Canby called it “a extravagant mess”. The movie was such a critical and commercial disaster that it was pulled from cinemas after just two weeks; the failure led to Hopper’s virtual exile from Hollywood for nearly a decade.

“Freedom’s just another word for nothin' left to lose”

James Taylor, Dennis Wilson and Laurie Bird in Two Lane Blacktop [1971]

|

Still hopeful of repeating the success of Easy Rider, Universal hired Monte Hellman, the director of two starkly original westerns for Roger Corman – Ride in the Whirlwind (1965) and The Shooting (1967) – to make Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), an existential road movie written by underground writer Rudy Wurlitzer about two young men drifting from town to town in their ’55 Chevy making money from drag races. Rock musicians James Taylor and Dennis Wilson were cast as the unnamed lead characters opposite Warren Oates as a middle-aged braggart who challenges the pair to a race across the country. Hellman, though, was less interested in showing the consequences of this showdown than in evoking an unsettling mood of loss and loneliness in his characters; their laconic Zen-like calm masking an apparent wilful indifference, an impression effectively captured in the final scene as the driver (Taylor) accelerates so recklessly toward the finishing line of a race that the film frame literally burns and fragments.

Less opaque but no less nihilistic, Richard Sarafian’s Vanishing Point (1971), starred Barry Newman as Kowalski, a Vietnam vet and ex-racing car driver, who accepts a challenge from a drug dealer to drive from Denver to San Francisco in a seemingly impossible time. Hopped up on Benzedrine, he refuses to stop for two motorcycle cops and a high-speed chase ensues. Outpacing his pursuers, he encounters a series of colourful characters on route, all the time spurred on by the voice of a black DJ on the radio who celebrates him as “the last American hero”. Like the characters in Two Lane Blacktop, his refusal to compromise ends in flames and apparent, though unconfirmed, death.

Both these “road movies” were essentially updates of the Western – a genre that has always been a barometer of the changing mores of American society. Though not achieving the same kind of success as Easy Rider, for the post-Woodstock generation, their anti-authoritarian, outlaw stance, philosophical and spiritual perspective and rock-fuelled soundtracks hit just the right note.

THX 1138 and the end of the Zoetrope dream

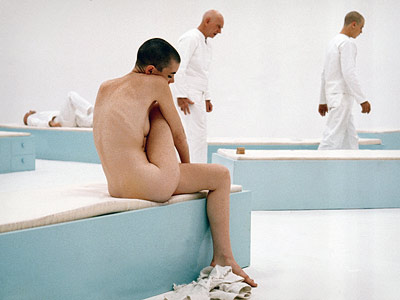

THX 1138 [1971]

|

While other studios were courting the new youth audience with varying degrees of success, Warner Brothers were less than enthusiastic about their collaboration with the independent company American Zoetrope. The first film to emerge from their partnership – George Lucas’s bleak, distopian science-fiction opus THX 1138 – grew out of a student short he had made in 1967 while attending USC filmschool. Confident of his friend’s abilities, Francis Ford Coppola had encouraged Lucas to follow his vision without compromise, but when the executives at the studio screened a first cut, they were appalled. They blamed Coppola for failing to supervise the production properly, and shortly after the screening, took the film away from Lucas and re-cut it in an effort to make it more commercial.

Indeed, so upset were Warner Brothers by THX 1138 that they consequently rejected the other six Zoetrope scripts (including The Conversation and Apocalypse Now) Coppola had submitted to the studio and terminated their deal with the independent company. In addition, they informed Coppola that Zoetrope would have to repay, not only the $300,000 the studio had loaned him for outfitting his premises in San Francisco with state of the art equipment, but also an additional $300,000 the studio had spent developing the scripts. Coppola had no choice but to agree, although he lacked the means to do so. Indeed with Zoetrope effectively bankrupt and his reputation in tatters, Coppola’s career prospects looked decidedly gloomy.

The Last Picture Show

Peter Bogdanovich directing Cybill Shepherd in The Last Picture Show.

|

By contrast, another alumni of the Roger Corman school of filmmaking, Peter Bogdanovich, was finding the path to success considerably easier. Impressed by the budding auteur’s first feature, Targets (1968), Bob Rafelson had offered to produce his next picture through BBS. Bogdanovich suggested an adaptation of Larry MacMurty’s The Last Picture Show, a coming-of-age story set in a small town in Texas in the 1950s. Though the novel’s milieu was far-removed from his own background, Bogdanovich and his wife, production designer Polly Platt, decided that their strategy would be to treat the adaptation as “the French would have made it, where these weird American sexual mores could be investigated”. Bogdanovich also made the key stylistic decision, suggested by his friend Orson Welles, to shoot the film in black and white in homage to John Ford and the classic American cinema of the 1940s, choosing veteran Robert Surtees as cinematographer.

Filming began in October 1970 in Archer City (renamed Anarene in the movie), the Texas town where McMurtry had grown up. Great attention was paid to ensuring the authenticity of every period detail from clothing to magazine covers to motel signs. The film’s cast featured the then unknown young actors Timothy Bottoms and Jeff Bridges as high-school seniors Sonny and Duane, and making her acting debut, fashion model Cybill Shepherd as Jacy, the most desirable girl in town. The fine supporting cast included Ellen Burstyn as Jacy’s mother; Cloris Leachman as the depressed, middle-aged wife of the high-school coach who has an affair with Sonny; and veteran Western actor Ben Johnson as Sam the lion, the sage proprietor of the pool hall and mentor to the boys. On set Bogdanovich played the role of “director” to the hilt, alienating much of the crew, yet he succeeded in eliciting compelling performances from the actors and in producing rushes that Rafelson assured a sceptical Bert Schneider would “cut like butter” in the edit suite.

The Last Picture Show [1971]

|

Rafelson’s confidence in Bogdanovich’s abilities turned out to be justified when The Last Picture Show was released to instant acclaim. Newsweek’s Paul D. Zimmerman began his review by declaring The Last Picture Show to be a masterpiece and “the most impressive work by a young American director since Citizen Kane.” Andrew Sarris, writing in The Village Voice saw it as a triumph for auteurism, claiming that Bogdanovich had “won over many of his erstwhile enemies by providing them with an emotional experience they did not anticipate.” The critical praise was reflected in the film’s eight Academy Award nominations (it won two: Ben Johnson for Best Supporting Actor and Cloris Leachman for Best Supporting Actress) and considerable commercial success (the seventh highest grossing film of 1971 in America).

The French Connection, Klute and the New Hollywood thriller

Far from Bogdanovich’s nostalgic vision of a lost rural America, two films released in 1971 re-imagined the contemporary urban thriller for a new generation. Inspired by the unadorned directness of classic Hollywood movies and the stylistic innovations and moral ambiguities of European cinema – most notably Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960) and Costa-Gavras’s Z (1969) – director William Friedkin brought a new level of gritty urban realism to the hugely successful crime drama The French Connection. Like Altman, Friedkin worked in television in his native Chicago for years before moving to Hollywood and breaking into features with the Sonny and Cher vehicle Good Times in 1967. He followed this up with a period comedy (The Night They Raided Minskys), a Harold Pinter adaptation (The Birthday Party), and an early study of gay life in New York (The Boys in the Band), but all failed to make much of an impression at the box office.

Roy Scheider and Gene Hackman in The French Connection [1971]

|

A frustrated Friedkin felt himself becoming side-lined as an art-house director until a chance meeting with Howard Hawks, the father of his then girlfriend Kitty, proved decisive. Referring to Boys in the Band, the hard-boiled Hawks said, “I don’t know why you’d want to make a picture like that. People don’t want stories about somebody’s problems or any of that psychological shit. What they want is action stories”. Friedkin took the advice to heart, later commenting that, “I had this epiphany that what we were doing wasn’t making fucking films to hang in the Louvre. We were making films to entertain people and if they didn’t do that first they didn’t fulfil their primary purpose. It’s like somebody gives you a key and you didn’t even know there was a lock; it led to The French Connection”.

Adapted from a non-fiction book by Robin Moore, The French Connection told the story of two New York Police detectives, Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle (Gene Hackman) and Buddy “Cloudy” Russo (Roy Scheider), who set out to bust a French drug smuggling ring lead by the suave Alain Charnier (Fernando Rey). Applying what he’d learned making television documentaries, Friedkin shot on location using hand-held cameras and mostly available light, lending the film a remarkable sense of verisimilitude. Much of the action and dialogue was improvised during production under the supervision of Narcotics Detectives Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso, the real-life counterparts of Hackman and Scheider’s characters. The film’s most celebrated scene – a blistering car chase between a car and an elevated train through New York’s crowded streets – set a new benchmark in high-velocity action sequences. This scene, and Hackman’s powerhouse performance, helped the low-budget film win 5 Academy Awards, including Best Actor, Best Picture and Best Director and become the third-highest-grossing film of the year.

Jane Fonda in Klute [1971]

|

Klute (1971), directed by Alan J. Pakula, starred Jane Fonda as a high-class prostitute who assists a detective played by Donald Sutherland to solve a missing person’s case. It also drew on the traditions of earlier Hollywood thrillers, in particular the private-eye, mystery genre. The two main characters: Bree Daniels, a self-destructive call girl, and John Klute, a square suburban investigator, though, were far removed from the duplicitous femme fatale and wisecracking detective archetypes familiar from The Maltese Falcon (1941) and countless other film noirs. Hiding vulnerability beneath a professional, cool facade, both characters become increasingly emotionally dependent on each other as Daniels's life comes increasingly under threat, though at the end of the film the future of their relationship is far from certain.

Pakula’s Klute was the first of three “conspiracy thrillers” (The Parallax View and All the President’s Men followed) the director made in the 1970s that effectively evoked the uncertain political climate and sense of paranoia prevalent in America at the time. Their distinctive look, created in collaboration with cinematographer Gordon Willis, established a new visual aesthetic for the times. Willis’s atmospheric lighting and painterly compositions represented a stylistic return to classicism, through the pacing, dialogue and ambiguous editing felt distinctly modern. The characterisation too, felt contemporary; Fonda’s performance, in particular, drew high praise for its intelligence and intensity, winning her the Best Actress Oscar at the 1972 Academy Awards.

Hal Ashby and the New Hollywood Comedy

a young Hal Ashby

|

Comedy was also changing, reflecting the preoccupations of a younger generation as new voices emerged. Among the most assured of these new voices was Hal Ashby. Born into a large Mormon family in Utah in 1929, Ashby dropped out of high-school at the age of 14 and began working in a series of odd jobs, an experience that gave him a life-long sympathy for society’s outsiders and underdogs. In 1950 he decided to leave behind the cold winters of his home state for a new life in California but spent his first weeks in Los Angeles virtually destitute. Down to his last candy-bar, he visited the Board of Unemployment and requested a job at a film studio. They sent him to work in the mailroom at Universal. After a few months he found work as an assistant editor at Republic, later moving on to Disney and MGM where he assisted on features by such high-profile directors as William Wyler and George Stevens. Eventually he graduated to lead editor on films such as The Loved One (1965), The Cincinnati Kid (1965) and In the Heat of the Night (1967), for which he won the Academy Award for Best Editor.

In 1969, aged 40, at the instigation of his friend director Norman Jewison, Ashby finally got the chance to direct his first feature. Adapted from a novel by Kristin Hunter, The Landlord starred Beau Bridges as a wealthy young man from a WASP background who buys an inner-city tenement house with the intention of turning it into a luxury house for himself but ends up abandoning his plans after befriending its eccentric black occupants. Contrasting the two worlds of its characters, Ashby proved himself an adept satirist with an offbeat sensibility.

Hal Ashby directing Bud Cort in Harold and Maude [1971]

|

It was these qualities, as well as Ashby’s abilities as a filmmaker, that caught the attention of Peter Bart at Paramount who was looking for somebody with a somewhat skewed perspective to direct a similarly eccentric story. Titled Harold and Maude, the script was about a young man who repeatedly tries to commit suicide until he meets and falls in love with a spirited 79-year-old woman who teaches him some valuable lessons about the importance of making the most life. It was the kind of unconventional story that could only have been produced at the time. As Bart later recalled: “To me, Harold and Maude was a symbol of that era. It would have been unthinkable in the 80s or 90s. In those days people would walk in, wacked out, with the most mind-bending, innovative and brilliant ideas for movies”.

For Ashby, an enthusiastic participant in the counter-culture, Harold and Maude was the perfect vehicle with which to express his own alternative world-view. Striking just the right balance between happy, sad and funny, he turned a film that might have come across as trite or preachy into a celebration of non-conformism in opposition to the cynicism of straight society. Featuring appealing performances from Bud Cort and Ruth Gordon in the lead roles and complemented by a catchy soundtrack performed by Cat Stevens, Ashby and Paramount were confident they had a hit on their hands. The studio opened the film during Christmas 1971 in time for Oscar consideration, although, as it turned out, reviews for the film were scathing, with Variety’s critic describing the film as “about as funny as a burning orphanage”. In the years to come the film would win a devoted audience and come to be regarded as a classic, vindicating Ashby’s vision, but at the time Paramount were discouraged by the reviews and pulled it from cinemas in a week.

“I got poetry in me!”

Robert Altman directing Julie Christie in McCabe and Mrs Miller [1971]

|

After M*A*S*H, Robert Altman made Brewster McCloud, a bizarre fable on the theme of non-conformity. In the title role, Bud Cort, reprising the alienated outsider persona of Harold and Maude, plays a young man living in the fallout shelter of Houston Astrodome, whose determination to fly using a pair of home-made wings, ends in tragedy. Too esoteric for a mainstream audience, Brewster McCloud's failure at the box office may have persuaded Altman to stick to more traditional genres in the films he made immediately after it.

The first of these, McCabe & Mrs Miller (1971), was a western, but unlike any that had come before. While its narrative, concerning the partnership that develops between a gambler and a whore and the violent conflict that ensues when he pits himself against ruthless commercial interests was conventional enough, Altman’s treatment of it was anything but. He described the film as an “anti-Western” and was clearly set on avoiding the clichés and challenging the conventions of the genre. Characteristically he focused as much on capturing the realism of the setting and the harsh lives of those living in it, as he did on the central story. Thus he had the town where the story takes place built from scratch in the Montana wilderness and encouraged cast and crew to live there during the course of the production. When it came to filming, Altman instructed cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond to shoot from a long distance using the zoom lens so that the actors could never be sure if they were in the frame or not. This and other techniques helped give the film a tremendous sense of spontaneity and life. As Warren Beatty, the film’s star, later commented, “Bob had a talent for making the background come into the foreground and the foreground go into the background, which made the story seem a lot less linear than it actually was.”

`Warren Beatty as McCabe

|

Thematically too, the film turned convention on its head. The frontier town where the story takes place is not so much a wilderness waiting to be civilized as a chaotic, muddy shantytown full of hustlers, profiteers and drunks. When Warren Beatty’s McCabe first rides into town his reputation as a tough gunslinger and skilled gambler gives him status in the town but as the story progresses he proves to be more of a fool than a conventional hero – inept at business and a failure in romance. Julie Christie’s pragmatic Mrs Miller sees through McCabe’s bluff and has no patience for his big talk. She’s right to be sceptical: his self-mythologizing soon unravels when he overplays his hand in negotiations with the company men and real killers come gunning for him.

Yet for all its iconoclasm, McCabe & Mrs Miller was one of the most poetic films of the 1970s. Zsigmond’s inspired decision to flash-expose the film stock before shooting resulted in the film’s distinctive hazy, antique patina so perfectly complimented by the mournful songs of Leonard Cohen, which might have been written especially for the film, but were in fact taken retrospectively from the songwriter’s first album.

As a haunting elegy for a mythic past, McCabe and Mrs Miller spoke volumes about the disillusionment of its own times.

“Violence makes violence.”

Two years into the new decade the war in South East Asia continued to rumble on, while at home, radicalism and increasing use of recreational drugs and rising crime rates led many to fear a break down in society was imminent. One of the biggest hits of 1971, Don Siegel’s stylish action thriller Dirty Harry starring Clint Eastwood as the tough, Magnum-45-wielding, San Francisco cop of the title, offered its audience a defiant counterblast to this mood of anxiety. Its portrayal of a lone hero taking the law into his own hands in order to save an innocent victim’s life may have offended some – leading to accusations of fascism and protests outside cinemas – but for others it represented a reassuring return to the straightforward morality of the classic Western.

Sam Peckinpah evoked a similar tradition in the harrowing Straw Dogs (1971) in which Dustin Hoffman’s mild-mannered mathematician turns vigilante after a gang of brutal locals from the English village to which he has moved to escape the violence of America, rape his wife and attempt to force their way into his house. Inspired by theories put forth in Robert Ardrey’s books African Genesis and The Territorial Imperative, which argued that man was essentially a carnivore who instinctively battled over control of territory, the film caused a storm of controversy on its release. Among its critics was Pauline Kael, who, while praising Peckinpah’s artistry, described Straw Dogs as “the first American film that is a fascist work of art”.

A Clockwork Orange [1971]

|

1971’s onscreen mayhem continued in Stanley Kubrick’s chilling adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s dystopian novel of a future Britain, A Clockwork Orange. Starring Malcolm MacDowell as Alex, the sociopathic leader of a gang of teenage delinquents, the film featured graphic scenes of rape and violence staged with brilliant operatic precision by its director. While it was these elements that sparked controversy and newspaper headlines, it was the film’s complex examination of free will that made it one of the most philosophically resonant screenworks of its time. Alex’s nihilistic pursuit of kicks is, the film suggests, a lesser evil than the state’s attempt to eliminate his destructive impulses through psychological conditioning. After conditioning he is less of a threat to society but also less human: he is “good” but not because he has chosen to be so.

The release of A Clockwork Orange, Straw Dogs, Dirty Harry and The French Connection set a new precedent in the depiction of graphic violence on screen. Essentially pessimistic in tone, they represented a fundamental philosophical and political shift from the idealism of the 1960s, yet their success at the box office showed audiences were ready to embrace the new trend despite the forebodings of some critics.

Coming soon: New Hollywood 1972-onwards

Return to: 'American New Wave' home. |