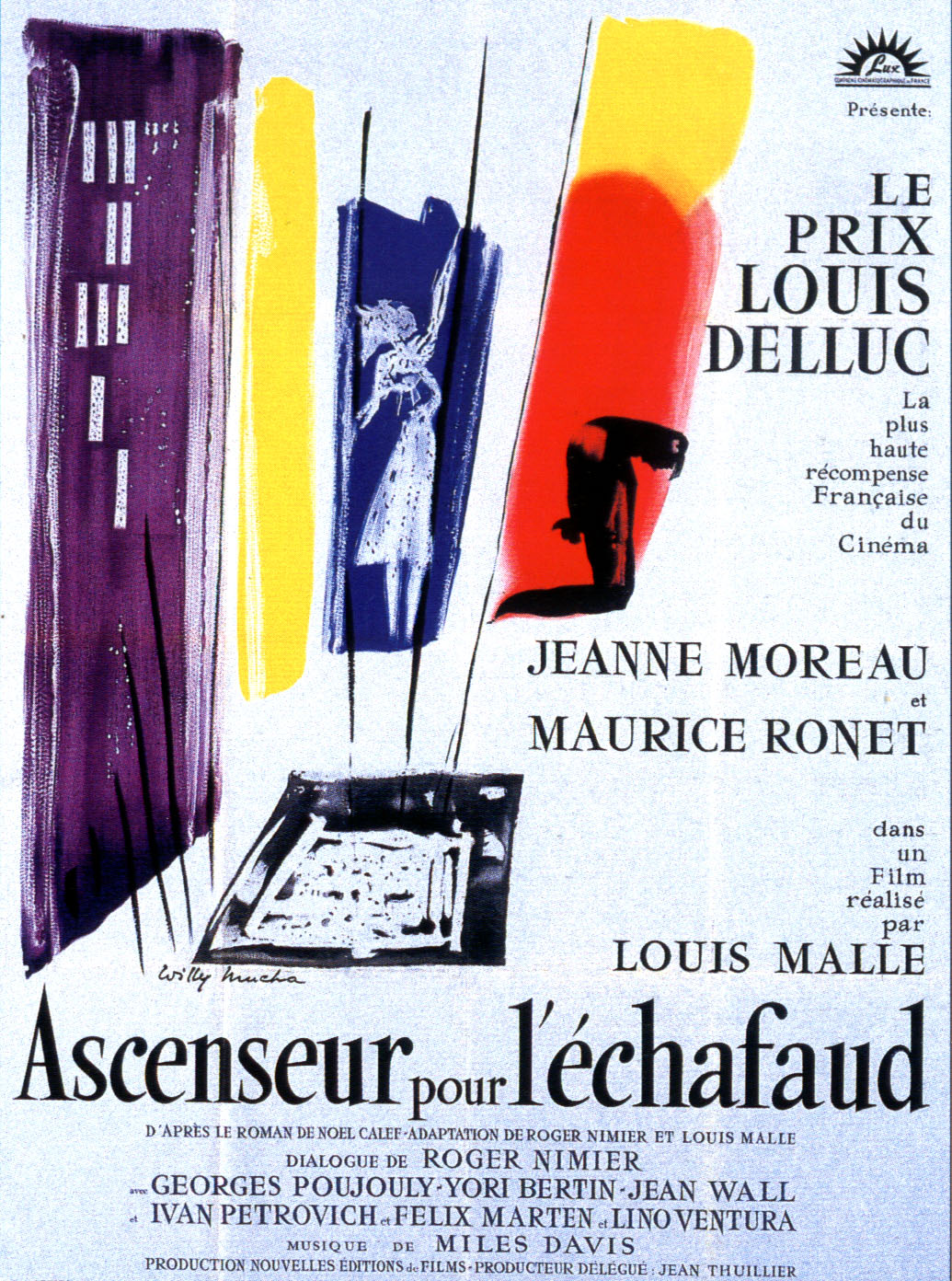

Ascenseur pour l'échafaud

[Elevator to the Gallows]

"I was split between my tremendous admiration for Robert Bresson and the temptation to make a Hitchcock-like film."

– Louis Malle

| Cast & Credits | Character | Actor | |

Director ....................................... |

Louis Malle | Florence Carala ............................ | Jeanne Moreau |

| Producer ...................................... | Jean Thuillier | Julien Tavernier ............................. |

Maurice Ronet |

| Screenplay .................................. | Noel Calef, Louis Malle, Roger Nimier | Louis .............................................. | Georges Poujouly |

| Cinematographer ........................ | Henri Decae | Veronique ..................................... |

Yori Bertin |

| Editor ........................................... | Leonide Azar | Simon Carala ................................ | Jean Wall |

| Composer .................................... | Miles Davis | Police Commissaire Cherrier ........ | Lino Ventura |

| Why it’s important? Ascenseur pour l’échafaud, or Elevator to the Gallows in its English translation, stands at a stylistic crossroads in French cinema between the crime thrillers of an older generation of directors such as Jacques Becker (Touchez pas au Grisbi, 1954) and Jean-Pierre Melville (Bob le flambeur, 1956), and the debut works of Malle’s contemporaries in the Nouvelle Vague which immediately followed it. Like the former, Malle adapted the stylistic and thematic motifs of classic American Film Noir to a French context, while at the same time introducing new cinematic and storytelling innovations that would influence others. This, combined with the film’s modern settings, its iconic new generation of actors, and its cutting-edge jazz score have led some – including the editorial team here at newwavefilm.com – to cite Elevator to the Gallows as the first French New Wave film. Louis Malle was just 24 when he directed Elevator to the Gallows (25 when it was released) – an extraordinary achievement and highly unusual in French cinema at that time. The film’s subsequent critical and commercial success launched not only Malle’s career, but also inspired other young directors to follow in his footsteps and gave producers the confidence to back them. Although acclaimed as the greatest French stage actress of her generation, Jeanne Moreau had yet to make a significant mark in cinema, despite having appeared in some twenty films. For the first time in Elevator to the Gallows, she had a challenging enough role to show her potential as a film actress. Her powerful onscreen presence in the film, and Malle’s next film, Les Amants (The Lovers, 1958), established the persona that would make her one of the biggest stars of European cinema over the course of the next decade. Miles Davis was already one of jazz music’s leading lights when he recorded the soundtrack for Elevator to the Gallows. Improvised and recorded over the course of one night, the score had a transformative effect on the film, helping to define its mood and sense of style. In turn, the film inspired one of Davis's most acclaimed and important early recordings, described by jazz critic Phil Johnson as "the loneliest trumpet sound you will ever hear and the model for sad-core music ever since." Production Notes Louis Malle’s rapid ascent had begun several years before, when, while still a film student in Paris, he had been recruited by oceanographer Jacques Cousteau as a camera operator on the undersea documentary Le Monde du silence (The Silent World, 1956). During the long months at sea, Malle became technically proficient in all aspects of production and so indispensible to Cousteau that he eventually credited his young assistant as co-director on the film. This generous gesture proved especially fortunate for Malle when the film won the Palme D’Or at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival. Determined to take advantage of his lucky break to kick-start his directorial ambition, Malle wrote an autobiographical screenplay but producers rejected it, advising him to write something more commercial instead. He found the vehicle he was looking for in a pulp novel called Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (Elevator to the Gallows) written by Noel Calef whose plot had the kind of clockwork precision favoured by Hollywood producers. Malle pitched the project to Jean Thuillier, who he had met the previous year while working as an assistant director on Robert Bresson’s Un condamné à mort s'est échappé ou Le vent souffle où il veut (A Man Escaped, 1956), who agreed to produce the film if they could attract the right cast and sell it to a distributor. First Malle set about writing a screenplay in collaboration with a young novelist called Roger Nimier, whose acclaimed novel Le Hussard Bleu (The Blue Hussar), had inspired a literary movement which opposed Existentialism and its politically engaged adherents led by Jean-Paul Sartre. Malle shared Nimier’s pessimistic view of contemporary society; a world in which, in the words of critic Rene Predal: “bitter, self-destructive, exhausted characters are lost in an old world without ideals, where the new generation does not know which values to follow.” Nimier didn’t think much of the book but agreed to work on the screenplay on condition that they start from scratch. Malle later said: “We changed practically the whole story, just keeping the basic plot.” Throwing out the clichés, they fashioned a screenplay relentless enough in its escalating tension to appeal to the most discerning fans of the genre, yet coloured by the kind of themes that would reappear in Malle’s work in the years to come. Most importantly, they built up some of the characters, particularly Florence Carala, played in the film by Jeanne Moreau, who barely existed in the book. Malle cast Moreau as Florence after seeing her in the Paris stage production of Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. In the role of her lover – the tough ex-soldier Julien Tavernier – Malle cast Maurice Ronet, who had begun to make a name for himself in such films as André Michel's La Sorcière (1956) and Jules Dassin's Celui qui doit mourir (He Who Must Die, 1957). As Louis, the young car thief turned killer, Malle chose Georges Poujouly, who had won acclaim as a child actor in Rene Clement’s Jeux interdits (Forbidden Games, 1952). With the cast in place, Malle made the crucial decision to hire Henri Decae as cinematographer, whose work on Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob le flambeur (1956) had particularly impressed him. Decae was both technically proficient, and crucially for Malle, willing to experiment. However, their unorthodox methods soon got them into trouble once production got underway Among the first scenes they shot were of Jeanne Moreau walking along the Champs Élysées at night, lit only by the lights from the shop windows. This had never been done before and was only made possible because they were using Tri-X, a new fast film, which serious filmmakers at the time thought too grainy. When technicians at the film lad saw the rushes they were appalled. They went to the producer and said: “you must not let Malle and Decae destroy Jeanne Moreau.” But Thuillier stuck by his creative team and the technicians backed down. His faith proved justified as these moody, introspective scenes are amongst the most powerful and original in the film. Malle’s long apprenticeship on The Silent World had given him the confidence to take such technical risks, but when it came to acting, Malle later admitted he was a lot less sure of himself: “When I did Ascenseur I was scared to death of actors, just because I had no experience of dealing with them. And if it had not been for Jeanne Moreau, who was incredibly helpful in the first two films I did with her – well, I was such a novice, I knew so little about it…” One thing Malle did know about was jazz music. A devoted fan since his early teens, he was at the time listening to a lot of Miles Davis. He even included a Miles Davis record sleeve in the room of the teenage girl, Veronique. Then, by coincidence, while he was editing the film, Davis came to Paris to play in a club for a short engagement. Through his friend, the writer and musician Boris Vian, then director of the jazz department at the Phillips record company, Malle arranged to meet with Davis to discuss his composing the soundtrack for the film. At first the musician was reluctant because he didn’t have his usual musicians with him, but Malle managed to convince him. He showed Davis the film twice and they agreed on the parts where they felt music was needed. Taking advantage of the one night off Davis had from the club where he was performing, Malle rented a sound studio in Paris on the Champs Elysees. Here, Davis, drummer Kenny Clarke, and three French session players, worked from ten at night until five the next morning, improvising the music while watching each scene of the film loop around, eventually recording the whole score in one night. Reception Released on January 29th 1958 in Paris, Ascenseur pour l’échafaud was a major critical and commercial success, winning the Prix Louis Delluc for Best Film and drawing large audiences. The film has been successfully re-released a number of times since its original release – most recently in a newly restored print in America in 2016. Moreau’s performance and Davis’s music are frequently singled out for praise in retrospective reviews. What is it about? A world without values In making Elevator to the Gallows, Malle was determined to portray Paris in a way that hadn’t been shown on screen before. As he explained years later in an interview with Philip French: “Traditionally, it was always the Rene Clair Paris that French films presented, and I took care to show one of the first modern buildings in Paris. I invented a motel – there was only one motel in France and it was not near Paris, so we had to shoot it in Normandy. I showed a Paris, not of the future, but at least a modern city, a world already somewhat dehumanized.” This modernity reflects a changing world in which the long-held values of the past are looking increasingly out of date. It can be seen in the state-of-the-art glass and concrete architecture of the Carala building; in the insolent attitude of the leather-jacketed teenagers (a new phenomenon in France at that time); and most of all, in the characters’ general mood of cynicism. A duel with society Both Florence and Julien have status and wealth, yet temperamentally they’re outsiders from bourgeois society who are prepared to risk everything in order to be together. Louis and his girlfriend Véronique may come from a different social milieu, but their defiant determination to live by their own rules represents an equally reckless gamble for freedom. As Malle later observed: “I’ve always been interested in characters who are breaking with the past. After living a conventional life, they come to a moment of crisis and suddenly reject the rules of the game. They’re swept along to a critical point where there’s no turning back, and it becomes a sort of duel between them and society.” The shadow of war Although not an overtly political film, France’s colonial wars in Indochina and Algeria are frequently mentioned, and by implication, influence the actions of the characters. Julien Tavernier, a veteran of the war in Indochina, is a man who has learnt to kill in the service of his country. Simon Carala, the man he murders, has made a fortune because of them. The jovial German businessman who patronises the teenage Louis hints at his own wartime past, prompting Louis to fabricate his own imaginary combat experiences. In post-war Europe, war seems to be on everybody’s mind; it may be taking place in a distant foreign climb but nobody can escape the fall out. Alone in the dark Anyone familiar with the classic tropes of film noir will recognize Elevator to the Gallows as a textbook example of the genre. Morally ambiguous and pessimistic in tone, its melancholic mood leaves an unforgettable impression. Florence and Julien’s desire to be together is thwarted at every turn by the twists and turns of coincidence and chance. In fact, during the course of the twenty-four hours in which the film takes place, they never meet in person; their fleeting moments of happiness – captured in the photographs that condemn them – are already over by the time the film begins. Prevented from communicating with each other and unable to confide in anybody else, both turn inward, alone in the dark and lost in their own despair. Trapped Both literally, and metaphorically, Elevator to the Gallows is about the experience of being trapped. By conspiring to commit murder, Florence and Julien believe they can escape the unhappy circumstances of their lives. Yet one slip up sets off a series of ill-fated consequences leading to further entrapment. When, through a piece of good fortune, Julien finally escapes from the elevator, his taste of freedom is all too brief: the wheels of fate have already turned, condemning himself and Florence to a future inside a prison cell with no hope of escape. Style Elevator to the Gallows is one of the most stylish films of its era. It’s beautiful black and white images, fluid mise-en-scène, and moody jazz score still impress almost half a century after it was first released. While perhaps not as formally adventurous as the debut works of Chabrol, Rivette, Truffaut or Godard that would immediately follow it, Decae’s tracking shots of Jeanne Moreau walking along the Champs-Élysées from a moving wheelchair predate Godard’s À bout de souffle (Breathless) by two years. Malle later commented in an interview that in making the film he was split between his admiration for Robert Bresson, with whom he had worked as assistant director the year before on A Man Escaped, and the desire to make a Hitchcock style film. Taking his cue from these two masters, Malle adopts a tightly controlled visual and narrative style throughout the film. Both directors’ influence can be seen, in particular, in the scenes in the elevator. In the earlier scenes Julien’s desperate search for a way out resembles, in it’s precise detail, the work of Bresson. Later, when Julien attempts to climb down the lift shaft, Malle employs Hitchcockian suspense to riveting effect. The impact of Miles Davis’s soundtrack on the film, as Malle later acknowledged, cannot be overestimated: “What he did was remarkable. It transformed the film. I remember very well how it was without the music, but when we got to the final mix and added the music, it seemed like the film suddenly took off. It was not like a lot of film music, emphasizing or trying to add to the emotion that is implicit in the images and the rest of the soundtrack. It was a counter-point, it was elegiac – and it was somewhat detached. But it also created a certain mood for the film. I remember the opening scene; the Miles Davis trumpet gave it a tone, which added tremendously to the first images. I strongly believe that without Miles Davis’s score the film would not have had the critical and public response that it had.” Key moments In film noir best-laid plans frequently go awry and Elevator the Gallows is no exception. When, after shooting Carala, Julien leaves the office and starts up his car, he believes he has committed the perfect murder, but glancing back up at the building he realises that he has left behind the rope he used to climb up the outside of the building. Knowing that this will incriminate him, he rushes back into the building and gets caught in the elevator when the power is turned off. This is the point when the story really takes off, as a rapid series of twists derails the lovers' hope of a new life, and sets the story spinning off in unexpected directions. When the waiting Florence sees Julien’s car passing by, she mistakenly thinks he has run off with Veronique and left her behind. Devastated, she returns to her table, and in an extended close up we listen in on her thoughts as she contemplates the implications of the new turn of events. This moment of introspection signals a change of mood: as night falls, the pace slows, and Miles Davis’s melancholy trumpet sets the tone, as cinematographer Henri Decae brilliantly conjures up the atmosphere of Paris after dark. Searching desperately, but unable to find Julien, even at his favourite bar, Florence steps back out onto the street just as a clap of thunder signals an impending downpour. Fearing that Julien has abandoned her, she wanders the nighttime Paris streets, lost in despair. It’s a sequence of pure cinema that has little to do with plot, but everything to do with revealing Florence’s inner state of mind. Back inside the stalled elevator, the equally despondent Julien’s spirits rise when he discovers a removable panel in its floor. Malle builds suspense, intercutting between Julien’s attempt to climb down the elevator cable, and the bumbling night-watchman turning the power back on downstairs. Accelerating to a nightmarish crescendo, the scene ends with Julien alive but defeated, no longer hopeful of escape. Louis’ reckless behaviour reaches its culmination when he attempts to steal the German businessman’s car. When discovered, his impulsive decision to pull the trigger of Julien’s gun, not only seals his fate, but that of Julien and Florence too. In the film’s most poignant moment, Florence watches the photographs that have condemned her emerge from the developer. Showing herself and Julien in an earlier, happier time, their very ephemerality suggests a world in which happiness is fleeting and unlikely to last. Look out for The office building where Julien murders Carala and becomes trapped in the elevator still exists at 29 Rue de Courcelles, Paris. Across the street at 168 Boulevard Haussmann is the flower shop where Veronique works and where she meets Louis. Further along Boulevard Haussman, at number 182, is the café (then called Royal Carnée, now a restaurant called Finzi) where Florence waits in vain for Julien and where he is later arrested. After they steal Julien’s car, Veronique and Louis drive past the Hotel Friedland which is still there at 2 Avenue Friedland. In her search for Julien, Florence goes into Luigi’s Bar (now closed) at 6 Rue du Colisée where she meet’s his friend. The motel where Louis and Veronique spend the night was in fact in Normandy as this was the only motel in existence in France at the time. The next morning the two teenagers abandon the stolen car at Pont de Bir-Hakeim and return to her apartment at 55 Boulevard de Grenelle. After he murders Carala, Julien spots a black cat balancing on the balcony rail outside the office window, foreshadowing the murder plot’s eventual unravelling. Julien’s miniature camera is a Minox. It was originally developed as a luxury item, but gained notoriety from its use as a spy camera. The German tourists' Mercedes-Benz 300SL W198 Gullwing was the fastest production car of its day. Produced from 1954 to 1957, they originally sold for $11,000 USD. They are now highly sought-after collector cars selling in excess of $1 million USD. It was the first production car with direct fuel injection, which is why the characters mention that the engine has no carburetors. Lino Ventura, who plays Commissaire Cherrier, became a star in 1954 in his first film role as a gangster opposite Jean Gabin in Jacques Becker’s classic Touchez Pas au Grisbi, in which Jeanne Moreau also appeared. Jean-Claude Brialy and Charles Denner – who would go onto become leading actors in the films of New Wave – appear in small roles. Where do I go from here? Following Elevator to the Gallows, Malle, Moreau and Decae collaborated on the even more successful Les Amants (1958), in which Moreau again played the dissatisfied wife of a wealthy bourgeois businessman who longs to leave him for another man. More social drama than thriller, the film is very different in style and theme from its predecessor, but features another compelling performance from Moreau. Malle would also go on to work with Ronet again on his early masterpiece Le Feu follet (1963), playing another enigmatic outsider. Pessimistic but lyrical, this sympathetic study of a soul in torment shows Malle’s remarkable development as a filmmaker in the course of just five years. For moody and stylish studies of le crime passionnel, one need look no further than the films of Claude Chabrol. His ‘Hélène cycle’ films, made in the late 1960s and early 1970s, all involve a murder plot and a triangular relationship between two men and one woman. Drawing on the work of Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang and the film noir tradition, these suspenseful thrillers are highly recommended. |

Newwavefilm.com video essay