|

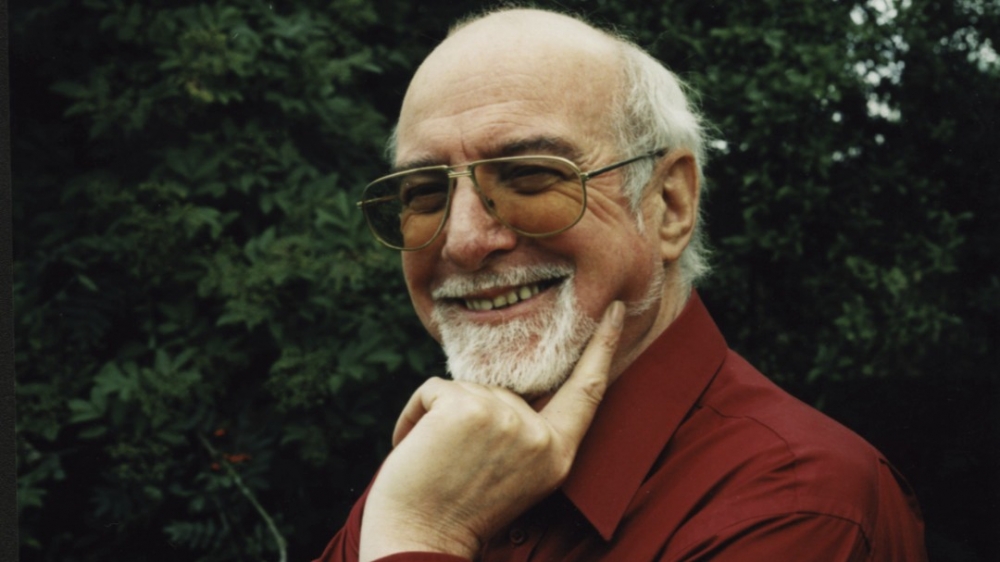

Peter Hames, author of The Czechoslovak New Wave |

Peter Hames is Visiting Professor in Film Studies, Staffordshire University and an expert on East Central European cinema. His books include The Czechoslovak New Wave (1985) and Dark Alchemy: The Films of Jan Svankmajer (1995). To celebrate the BFI’s season ‘Defiance and Compassion: The Films of Vera Chytilová (1 – 17 March 2015), we asked him for his insights into the life and career of one of the defining figures of the Czechoslovak New Wave.

I wanted to start by asking if you could briefly summarize, for those who might be discovering the movement for the first time in this season, how the Czechoslovak New Wave came to be, what made it unique, and the part that Vera Chytilová played in it?

|

director Vera Chytilová |

The New Wave is conventionally dated from 1963 and lasted until the Soviet invasion put an end to the Prague Spring reforms in 1968. However, many films passed for production in 1968 didn’t appear until 1969 and a few were even released as late as 1970. But I would put its dates at 1963-69, which is actually longer than the French New Wave. It wasn’t initially called a new wave – rather the Czech Film Miracle.

The three films that symbolized the breakthrough were the debut features of Miloš Forman (Black Peter, released here as Peter and Pavla), Věra Chytilová (Something Different), and Jaromil Jireš (The Cry). The main unifying factor of these early films was that they addressed everyday reality as experienced rather than creating false morality tales. They were followed by a whole range of debut directors, among them Jan Němec, Evald Schorm, Pavel Juráček, Jan Schmidt, Ivan Passer, Jiří Menzel, Hynek Bočan, Juraj Jakubiso, Dušan Hanák, Elo Havetta, and Drahomira Vihanová.

They tended to go in different creative directions and find their own individual approaches.

But while the attack on tradition and the falsifications of Socialist Realism, if one can put it that way, was spearheaded by the young directors, older directors had paved the way and joined in with the new freedoms experienced in the 1960s. A Shop on the High Street directed by Ján Kadár and Elmar Klos, which won the first Czech Oscar for best foreign language film in 1965, was a product of the older generation. Other names that are probably familiar include František Vláčil, Štefan Uher, Vojtěch Jasný, and Karel Kachyňa, all of whom made ground breaking films in the 1960s.

Most of the directors had trained at FAMU (the Prague Film School) and were familiar with trends in world cinema. The Dean used to arrange screenings of films even when they were turned down for distribution. Two significant film makers also emerged from a background in puppetry – Juraj Herz and Jan Švankmajer.

But alongside the particular freedoms of FAMU, the New Wave should be seen in the context of new directions in the arts generally and the pressure for social and political reform that developed both inside and outside of the Communist Party in the 1960s – a collective pressure that led to the abolition of censorship and the movement towards increased democratisation

Why has the British Film Institute decided to put on a retrospective of Chytilová’s films now, and what are some of the films that will be playing in the season?

The season is an initiative by the BFI and the Czech Centre in London. Obviously, there could have been seasons in earlier years (Chytilová attended an earlier retrospective at the Riverside Studios in 2002). I think one of the reasons is the increasing critical attention given to her work in recent years and, of course, the success of the DVD release of Daisies. Also, regrettably, her death last year has focused attention on her legacy.

Vera Chytilová was born in Czechoslovakia in 1929 and had a strict Catholic upbringing. At college she studied philosophy and architecture and then worked as a draftsman, fashion model and clapper girl for the Barrandov Film Studios before entering the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (FAMU) to study filmmaking at the relatively late age of 28. How do you think these life experiences influenced her film work?

She was interested in literature and the arts and these wider interests have obviously influenced her work – she once said that she was interested in everything, which made it difficult to narrow things down. Her first marriage was to the photographer Karel Ludwig, famous for his portraits of theatre stars, and that brought her into contact with a particular cultural environment that included people like the novelist Bohumil Hrabal and the artist Vladimír Boudník. You can see this in her short film, The World Cafeteria (part of Pearls of the Deep, 1965), based on Hrabal, which features both of them, and also in her more recent documentary Flights and Falls (2000).

When she first went before the examining board at the Film Academy she told the tutors that she wanted to make films because she didn’t like the films they made. She thought they were too predictable and throughout her career she was renowned, some would say notorious, for having a combative and uncompromising attitude. She even described herself as “an overheated kettle that you can’t turn down”. Do you think this is something that helped or hindered her craft as a director and auteur?

I think it probably helped – certainly in getting films made. She always argued that the bureaucrats who ran the industry in the 70s and 80s were scared of hysterical women and that she had no difficulty in fulfilling their expectations.

|

A Bagful of Fleas, 1962 |

Can you talk a bit about her early works: Ceiling (1961), A Bagful of Fleas (1962), and Something Else (1963)? Was anything established in those films, thematically or stylistically, that would persist through her later work?

All three films deal with the position of women in society, in fashion (Ceiling), in the factory (A Bagful of Fleas), in gymnastics, and marriage (Something Different). Unlike her post-Daisies films, these show the influence of “cinéma vérité”, but the documentary elements are also combined with formal interests. I would say that the desire to combine different formal elements is already there in Ceiling and, of course, Something Different combines two strands, a documentary about a champion gymnast and a fictional story with actors. Very few of her films follow the classical conventions she objected to in her FAMU interview. The desire to make unexpected combinations is a characteristic of most of her work. Also, I would say, the communication of subjective female experience.

By the mid-1960s the films of the Czech New Wave were attracting international recognition. Chytilová herself contributed a short to the omnibus film Pearls of the Deep, which showcased the work of a number of its key figures. To what extent did she fit into the movement? What was her relationship like with some of its other directors, and did she perceive her films as being part of the Wave?

People often say that the Wave wasn’t a unified movement – that everyone followed their own path. Yet Czechoslovakia was a small country and people worked on each other’s films, particularly at FAMU. Thus Jakubisko worked as assistant director on Chytilová’s Ceiling, Menzel was assistant director on her Something Different and played a lead role in The Apple Game. When it comes to cinematographers, the links become obvious. Jaroslav Kučera worked with Jasný, Jireš, Němec, Chytilová and Herz and the same could be said of others. The editor Miroslav Hájek worked with almost everyone. So, there were no manifestoes and people tried to find their own paths, but there was unity despite that. The only time they came together for a group photograph was to protest against the banning of Daisies.

|

Daisies, 1966 |

Daisies (1966) is still Chytilová’s best-known film. The story concerns two teenage girls who, believing the world to be “spoiled”, embark on a series of anarchic pranks in which nothing is taken seriously. Why do you think it had, and still has, such an impact on audiences?

I think it’s interesting that when Chytilová and Kučera went to New York in 1968, they made a point of visiting Andy Warhol’s Factory and were most interested in developments in underground film. I think Daisies is a rare example of an underground film surfacing from the depths – it’s also funny, accessible, and irreverent. It’s visually impressive with a whole host of special effects and innovations and matched by an equally unusual soundtrack.

It’s often categorized as a feminist film – do you think that was her intention?

I don’t think that feminism was a hot issue in Czechoslovakia in the 1960s and Chytilová has always denied being a feminist. She has always argued that the film is intended to be critical of the girls and their destructive attitudes. Perhaps identification became irresistible in some way. Kučera one said that they intended to use certain effects to criticize things, but the results turned out differently from what was expected.

The film was initially banned by the authorities in Czechoslovakia. Why do you think they objected to the film so much?

It was the object of a protest in the National Assembly initiated by a Mr. Pružinec (which according to the novelist Josef Škvorecký, translates as Mr. Jack-in-a-box).

It was signed by 21 other deputies, but it was also an attack on Němec’s The Party and the Guests and Martyrs of Love (also co-scripted by Krumbachová). The ban was not that long since the films were given a reprieve during the Prague Spring. I think they objected primarily to its avant-garde form, the fact that the girls didn’t provide a moral example, and they no doubt correctly saw it as an attack on establishment values.

|

Fruit of Paradise, 1969 |

As you’ve mentioned, Daisies was shot by Chytilová’s second husband Jaroslav Kucera, who also worked on her even more experimental subsequent film Fruit of Paradise (1969), an allegorical updating of the fable of Adam and Eve. What contribution did he bring to her work?

Kučera also worked with her on The World Cafeteria. His interest in giving greater force to the image was already evident in his work with Jasný (Desire [1958], When the Cat Comes [1963], and All My Good Countrymen [1968]) and Němec (Diamonds of the Night [1964]). Chytilová has spoken of how he was always experimenting at home and she wanted to bring this into their work together. He once said that he was particularly interested in making the cinematic image autonomous – separate from the conventional concept of film. Chytilová said that they worked together like ‘two peas in a pod’.

Fruit of Paradise is often cited as one of Chytilovå’s best films. What made it special?

The critical and audience reaction to The Fruit of Paradise was even more confused than the response to Daisies. As Chytilová said, it got released in 1970 because no one understood it. I think the major difference in this film rests with her use of actors from the Studio Ypsilon, then a regional theatre but subsequently a Prague theatre group. Experimental in their approach, they use stylized acting, drawing on the tradition of the commedia dell’arte. Added to this, of course, is Zdeněk Liška’s music score, which is continuous throughout (unlike her earlier films). At one stage, it was intended that the dialogue should be sung, so there’s also an operatic quality to the whole piece. And, of course, Krumbachová’s script and design and Kučera’s photography interact creatively as was the case in Daisies.

|

Soviet invasion of Prague, 1968 |

After the Prague Spring of 1968, Soviet forces invaded Czechoslovakia to halt the reforms of the Alexander Dubcek government and a more hard-line communist administration took over the country bringing the Czechoslovak New Wave to an abrupt end. Some of the filmmakers associated with the movement left the country as a result to work abroad including Milos Forman and Jan Nemec. Although she faced censorship at home, Chytilová didn’t join them. Why do you think she decided to remain living in her home country?

She was offered the chance to stay abroad but decided that her place was at home. In fact, most of the New Wave stayed at home – some had to find employment outside cinema. Evald Schorm worked in theatre, Pavel Juráček never worked again, others were only able to make documentaries or children’s films. Over 100 features from the 1960s were banned. Others such as Menzel and Jakubisko made late comebacks after having earlier films banned.

After the so-called ‘normalisation’ of the country by the Soviet-backed government, Chytilová didn’t work again until 1976 when, after a combination of international pressure and her own personal appeal to President Husak, she was allowed to go into production on her next film The Apple Game. Can you describe the events that led to this comeback?

Chytilová wrote an open letter to Husák in 1975 accusing the studio bosses of hostility and male chauvinism. She got to make her film The Apple Game in 1976 – but in the short film studios, headed by a man alleged to be a high up in state security. It was alleged that his support was designed to win him political advantage. Nonetheless, the authorities weren’t anxious to promote it and it was withdrawn from the Berlin Film Festival. It eventually went on to international success and was (reluctantly) released in Czechoslovakia the following year.

|

The Apple Game, 1976 |

As you say, The Apple Game was a great success, winning a Silver Hugo at the Chicago International Film Festival. From then onwards she would continue to make films in spite of the often-harsh restrictions placed on her by the funding authorities. What were some of the key films of this second phase of her career?

She made a further six feature films in the Communist period: Prefab Story (1979), Calamity (1981), The Very Late Afternoon of a Faun (1983), Wolf’s Cabin (1986), Jester and the Queen (1987), and Tainted Horseplay (1988). The most controversial was Prefab Story, a story of contemporary morality set against a background of the high rise apartments then being built on the outskirts of Prague (and characteristic of other Communist countries). Not only did it present a ‘negative’ image of government initiatives but almost nobody came out of it unscathed. It was not premiered until 1981 and not widely seen until much later. She had ‘difficulties’ with a number of her other films.

Eventually, the political changes of the late 1980s and early 1990s in Czechoslovakia meant the film industry changed too. In these later years, Chytilová received more recognition for her work including a Czech Lion Award for her contribution to her country’s cinema. Can you talk a little bit about how her work evolved during this period?

|

Chytilová at the Karlovy Vary Int'l Film Festival, 2007 |

Like other members of the New Wave, the new system didn’t provide the opportunities that had been hoped for. Chytilová led the film union in an attempt to prevent the denationalisation of the film industry which, they felt, would destroy efforts to maintain a national film culture. None of the members of the New Wave were able to continue or resume work with any regularity. Chytilová made four features: Inheritance (1992), Traps (1998), Expulsion from Paradise (2002), and Pleasant Moments (2006). They were all very different, but all had strong moral and political arguments. Traps, which is about a woman vet who castrates her abusers was actually advertised as a ‘feminist black comedy’. But while working on features proved difficult, she taught at FAMU and directed a range of documentaries – the most interesting being Flights and Falls (2000) about the still photographers Ludwig, Václav Chochola and Zdenek Tmej, which is a compelling social and cultural history that deserves a much wider audience.

What would you say is Vera Chytilová’s lasting contribution to cinema?

All her work from the 1960s was original and innovative and also made a significant contribution to women’s cinema. A number of critics have picked up on Daisies and The Fruit of Paradise as particularly relevant to women’s cinema because their freedom, fluidity, inter-subjectivity, and excess are seen as particularly relevant to female expression – to which I would add wit, sympathy, and observation. But the 1960s was certainly a unique period for Czech and Slovak directors with neither ‘normalisation’ nor capitalism allowing a return to those kinds of freedoms. I think her later work has to be viewed as a period of permanent struggle to realize her vision against the odds.

Interview by Simon Hitchman, © February 2015 - please do not reprint or reuse without permission. |