'What interests me in the cinema is abstraction.' - Orson Welles

One cannot help noticing that something is happening in the cinema

at the moment. Our sensibilities have been in danger of getting

blunted by those everyday films which, year in year out, show their

tired and conventional faces to the world.

|

Jean Renoir and Julien Carette in "La Regle du Jeu", 1939 |

The cinema of today is getting a new face. How can one tell?

Simply by using one's eyes. Only a film critic could fail to notice the

striking facial transformation which is taking place before our very

eyes. In which films can this new beauty be found? Precisely those

which have been ignored by the critics. It is not just a coincidence

that Renoir's La Regle du Jeu, Welles's films, and Bresson's Les

Dames du Bois de Boulogne, all films which establish the foundations

of a new future for the cinema, have escaped the attention of critics,

who in any case were not capable of spotting them.

But it is significant that the films which fail to obtain the blessing

of the critics are precisely those which myself and several of my

friends all agree about. We see in them, if you like, something of the

prophetic. That's why I am talking about avant-garde. There is

always an avant-garde when something new takes place... .

To come to the point: the cinema is quite simply becoming a

means of expression, just as all the other arts have been before it,

and in particular painting and the novel. After having been successively

a fairground attraction, an amusement analogous to boulevard

theatre, or a means of preserving the images of an era, it is gradually

becoming a language. By language, I mean a form in which and by

which an artist can express his thoughts, however abstract they may

be, or translate his obsessions exactly as he does in the contemporary

essay or novel. That is why I would like to call this new age

of cinema the age of camera-stylo (camera-pen). This metaphor has

a very precise sense. By it I mean that the cinema will gradually

break free from the tyranny of what is visual, from the image for its

own sake, from the immediate and concrete demands of the narrative,

to become a means of writing just as flexible and subtle as

written language. This art, although blessed with an enormous

potential, is an easy prey to prejudice; it cannot go on for ever

ploughing the same field of realism and social fantasy which has

been bequeathed to it by the popular novel. It can tackle any subject, any genre. The most philosophical meditations on human

production, psychology, metaphysics, ideas, and passions lie well

within its province. I will even go so far as to say that contemporary

ideas and philosophies of life are such that only the cinema can do

justice to them. Maurice Nadeau wrote in an article in the newspaper

Combat: 'If Descartes lived today, he would write novels.'

With all due respect to Nadeau, a Descartes of today would already

have shut himself up in his bedroom with a 16mm camera and some

film, and would be writing his philosophy on film: for his Discours

de la Methods would today be of such a kind that only the cinema

could express it satisfactorily.

It must be understood that up to now the cinema has been

nothing more than a show. This is due to the basic fact that all films

are projected in an auditorium. But with the development of 16mm

and television, the day is not far off when everyone will possess a

projector, will go to the local bookstore and hire films written on

any subject, of any form, from literary criticism and novels to

mathematics, history, and general science. From that moment on,

it will no longer be possible to speak of the cinema. There will be

several cinemas just as today there are several literatures, for the

cinema, like literature, is not so much a particular art as a language

which can express any sphere of thought.

|

Sergei Eisenstein |

This idea of the cinema expressing ideas is not perhaps a new one.

Feyder has said: 'I could make a film with Montesquieu's L''Esprit

des Lois.' But Feyder was thinking of illustrating it 'with pictures'

just as Eisenstein had thought of illustrating Marx's Capital in book

fashion. What I am trying to say is that the cinema is now moving

towards a form which is making it such a precise language that it

will soon be possible to write ideas directly on film without even

having to resort to those heavy associations of images that were the

delight of the silent cinema. In other words, in order to suggest the

passing of time, there is no need to show falling leaves and then

apple trees in blossom; and in order to suggest that a hero wants to

make love there are surely other ways of going about it than showing

a saucepan of milk boiling over on to the stove, as Henri-Georges Clouzot does in Quai des Orfevres (Jenny Lamour).

The fundamental problem of the cinema is how to express

thought. The creation of this language has preoccupied all the

theoreticians and writers in the history of the cinema, from Eisenstein

down to the scriptwriters and adaptors of the sound cinema.

But neither the silent cinema, because it was the slave of a static

conception of the image, nor the classical sound cinema, as it has

existed right up to now, has been able to solve this problem satisfactorily.

The silent cinema thought it could get out of it through

editing and the juxtaposition of images. Remember Eisenstein's

famous statement: 'Editing is for me the means of giving movement

(i.e. an idea) to two static images.' And when sound came, he was

content to adapt theatrical devices.

|

André Malraux |

One of the fundamental phenomena of the last few years has been

the growing realisation of the dynamic, i.e. significant, character of

the cinematic image. Every film, because its primary function is to

move, i.e. to take place in time, is a theorem. It is a series of images

which, from one end to the other, have an inexorable logic (or

better even, a dialectic) of their own. We have come to realise that

the meaning which the silent cinema tried to give birth to through

symbolic association exists within the image itself, in the development

of the narrative, in every gesture of the characters, in every

line of dialogue, in those camera movements which relate objects to

objects and characters to objects. All thought, like all feeling, is a

relationship between one human being and another human being

or certain objects which form part of his universe. It is by clarifying

these relationships, by making a tangible allusion, that the cinema

can really make itself the vehicle of thought. From today onwards,

it will be possible for the cinema to produce works which are

equivalent, in their profundity and meaning, to the novels of

Faulkner and Malraux, to the essays of Sartre and Camus. Moreover

we already have a significant example: Malraux's L'Espoir, the

film which he directed from his own novel, in which, perhaps for the

first time ever, film language is the exact equivalent of literary

language.

Let us now have a look at the way people make concessions to the

supposed (but fallacious) requirements of the cinema. Scriptwriters

who adapt Balzac or Dostoievsky excuse the idiotic transformations

they impose on the works from which they construct

their scenarios by pleading that the cinema is incapable of rendering

every psychological or metaphysical overtone. In their hands,

Balzac becomes a collection of engravings in which fashion has the

most important place, and Dostoievsky suddenly begins to resemble

the novels of Joseph Kessel, with Russian-style drinking-bouts in

night-clubs and troika races in the snow. Well, the only cause of

these compressions is laziness and lack of imagination. The cinema

of today is capable of expressing any kind of reality. What interests

us is the creation of this new language. We have no desire to rehash

those poetic documentaries and surrealist films of twenty-five years

ago every time we manage to escape the demands of a commercial

industry. Let's face it: between the pure cinema of the 1920s and

filmed theatre, there is plenty of room for a different and individual

kind of film-making.

|

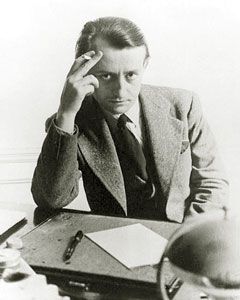

The young Orson Welles. |

This of course implies that the scriptwriter directs his own

scripts; or rather, that the scriptwriter ceases to exist, for in this kind

of film-making the distinction between author and director loses

all meaning. Direction is no longer a means of illustrating or presenting

a scene, but a true act of writing. The film-maker/author

writes with his camera as a writer writes with his pen. In an art in

which a length of film and sound-track is put in motion and proceeds,

by means of a certain form and a certain story (there can even

be no story at all - it matters little), to evolve a philosophy of life,

how can one possibly distinguish between the man who conceives

the work and the man who writes it? Could one imagine a Faulkner

novel written by someone other than Faulkner? And would Citizen

Kane be satisfactory in any other form than that given to it by

Orson Welles?

Let me say once again that I realise the term avant-garde savours

of the surrealist and so-called abstract films of the 1920s. But that

avant-garde is already old hat. It was trying to create a specific

domain for the cinema; we on the contrary are seeking to broaden

it and make it the most extensive and clearest language there

is. Problems such as the translation into cinematic terms of

verbal tenses and logical relationships interest us much more

than the creation of the exclusively visual and static art dreamt

of by the surrealists. In any case, they were doing no more than

make cinematic adaptations of their experiments in painting

and poetry.

So there we are. This has nothing to do with a school, or even a

movement. Perhaps it could simply be called a tendency: a new

awareness, a desire to transform the cinema and hasten the advent

of an exciting future. Of course, no tendency can be so called unless

it has something concrete to show for itself. The films will come,

they will see the light of day - make no mistake about it. The

economic and material difficulties of the cinema create the strange

paradox whereby one can talk about something which does not yet

exist; for although we know what we want, we do not know whether,

when, and how we will be able to do it. But the cinema cannot but

develop. It is an art that cannot live by looking back over the past

and chewing over the nostalgic memories of an age gone by.

Already it is looking to the future, for the future, in the cinema as

elsewhere, is the only thing that matters.