|

Dudley Andrew |

Dudley Andrew is a prominent figure in the field of film studies, recognized for his influential contributions as a scholar, critic, and educator. Throughout his career, Andrew has played a pivotal role in shaping the discourse around cinema, particularly in the realms of film theory and comparative literature. As a distinguished professor, he has held key academic positions at esteemed institutions, including the University of Iowa and Yale University.

In 1978 he published his acclaimed biography of the renowned French film critic and theorist André Bazin. Since then, he has edited further books and written numerous articles about Bazin (see the bibliography at the end of this article), as well as translating many of his writings into English. His most recent book French Cinema: A Very Short Introduction is published by Oxford University Press.

|

Andre Bazin |

André Bazin is often described as the most influential film critic and theorist who ever lived. Why do you think he is held in such high regard by so many people?

This question is crucial though it has two parts to it which don’t quite fit. Firstly, I think he is indisputably influential – that’s nobody’s opinion, it’s just the case. And secondly, he is esteemed, and that’s more about people’s subjective feelings about him.

The influential part arrives I think because of his close relationship, even before he was at Cahiers du cinéma, with Jean Renoir and with Jean Rouch. And then Luis Bunuel, who he discovered in Cannes in 1950, and with whom he later became friends, and with other directors that the New Wave were attached to. He also knew Orson Welles, who he’d met in 1948. And that gave him a kind of prestige with the New Wave directors, the future ones, and they stuck closely to him, because he had something special he knew about. So, Truffaut, Rohmer, Godard, Astruc, Cocteau – these directors all listened to him, and I think that just made people pay attention to him through the New Wave. That’s the reason for his influence, I think. He did influence those filmmakers, sometimes directly. They attributed some of the things they did to having talked to him and thought about what he said.

As for his esteem – well, I think there are three different ways. One is for his manner and way of living. People who knew him really admired what I call his Franciscan way of going through life delicately, being attentive to everything, and being self-effacing and trying to bring things out so people would love them more. But also, by his writings, which have most influenced me. I never got to meet him – I was fourteen when he died – but anybody who reads him closely, or even casually, can recognize an intelligence and a sympathy in his writing that is also rigorous. And finally for his ideas about the arts, the ambitions he had for cinema. He’s not prescriptive, but he was really ambitious for what the cinema could do, and he didn’t think the cinema was the end all of everything. He had ideas about culture and society that went beyond cinema, and that cinema played into. Especially now that people seem to be moving outside of the cinema realm, cinephilia doesn’t rule everything. Well, Bazin wasn’t just a cinephile. He saw every movie, but he was interested in much more than that. So, there’s admiration and esteem that he’s gathered more recently because of his larger ideas that go beyond those of his cohorts. So those are the two different things: his influence, which is actual on filmmakers that you can see, and then the esteem, which I think comes in those three ways.

Were there any writers or thinkers in particular who shaped Bazin’s intellectual and aesthetic philosophy in his early years?

|

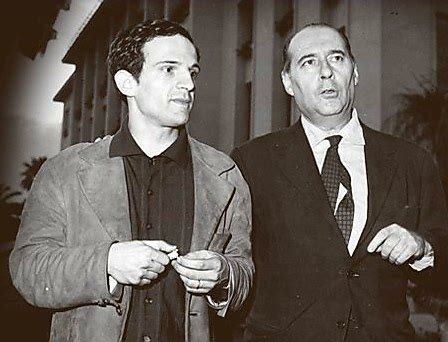

Roger Leenhardt |

Yes, there definitely were, and I try to go through some of them in the biography I wrote long, long ago, which still holds up, at least that part of it. His closest associates who got him writing about film were connected to the magazine Esprit, which I studied at length. It’s a really interesting magazine that was even more important than Les Temps modernes in French culture. It’s more read – the same type of readers though, intellectuals. Its writing has mainly been to do with the arts, but also social ideas. It was “Christian existentialist” I would say, and the two people he was most concerned with were Emmanuel Mounier, who had started it – he died in 1949 but Bazin knew him fairly well after 45 when he was recruited to be the film critic – and then there was Roger Leenhardt.

Leenhardt is a less known figure, but I think your New Wave readers should be interested in him. Leenhardt, who I got to meet, was the film critic of Esprit when it started in 1934 or 35. He was already writing his Little School of the Spectator, just trying to bring film into a conversation that Esprit kept up with theatre and the novel and so forth. He was a film editor, and he wrote intelligently about film, and he wrote in ways that engaged Bazin. So, when Bazin set up a film club in 1942, his first film club during the occupation at the Sorbonne, he invited Leenhardt because he knew him from Esprit. He had already started to read Esprit, and he had gone to hear Mounier and gotten to know the people there. Leenhardt came and they hit it off. Leenhardt was really involved in documentary, and he presaged some of Bazin’s interest in documentary. And then Leenhardt turned over his job as Esprit’s film critic to Bazin once the magazine started up again after the occupation ended. But they remained close and Leenhardt made a terrific film, Les Dernières vacances, that hasn’t been seen much in the US but has some reputation in France. Bazin championed that film, thinking of Leenhardt as really being a literary man, but also really good filmmaker. So, he was close to Leenhardt.

I should mention, now that I think of it, in terms of Bazin’s ideas about film and the novel, I’ve been increasingly interested in the first woman professor of literature from the Sorbonne, Claude-Edmonde Magny. She also wrote for Esprit, and I think he got to know her in 1944/45 when they met. Many of his ideas about film and the novel I think are presaged in her famous book that came out in English many years ago, The Age of the American Novel, where she talks about how American fiction writers were really influencing French fiction writers and the Americans got it from the movies. Bazin turned it around and said yes now the French filmmakers are picking up on what the American novelists have done, so he thought about Rosselini in relationship to Hemingway as a short story filmmaker. So, she was another important person in terms of his actual aesthetics.

Sartre was another really crucial influence, so the next level up would be Sartre, and Andre Malraux, who was a kind of hero for Bazin. Bazin joined a Malraux study group at the Sorbonne in 1941, and he wrote one of his very first essays on Malraux’s L'Espoir. It’s a beautiful essay; I didn’t realise how good until I translated it with my friend two years ago. Malraux recognised that and wrote him back, and that’s all published – it can be read. And Malraux remained influential because he then turned to the history of art, and Bazin interacted with him, his ideas at least, through his many volume history of art. Bazin was writing about films about art made by Resnais and Clouzot. This all comes back to the New Wave because everyone now realises how important Malraux was for the story of the New Wave when he was the one who allowed Truffaut’s 400 Blows to represent France at Cannes, it was his personal decision, and one of my favorite pieces of writing is Godard’s elation when he was at the screening. He was hanging out because he had access – he was in the press and had access to the screening room when Malraux was watching the film. Malraux said this film is going to represent France at Cannes, and people were astounded that this counter-cultural movie The 400 Blows should be so chosen, and Godard proclaimed it in a wonderful essay that has been published many times. So anyway, Malraux is important to Bazin.

The final group, who I would say is less well-known and maybe of less interest to people, is the kind of spiritual group that Bazin was involved with. He was, I think, from the beginning of his college time and grade school, influenced by some Catholics who were visionaries and one of them is Marcel Legaut. I talk about him in my biography, he’s not so well-known, but he’s a utopian figure, a priest who would take leftist Catholics into the countryside and try to start ideal communities. Bazin’s quite interested in his socialism. Then there’s Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who is a kind of guru figure for many people in the 50s and 60s with these wild ideas about evolution that goes beyond human beings into the cosmos. Teilhard was just getting to be famous at the time, and Bazin would go out and try to get people to go to his lectures. I think he pulled away from that later, but for a while Teilhard and his ideas about evolution were an influence. Bazin saw all the arts and everything in terms of evolution, and Teilhard had kind of the largest view of that, and he was involved intellectually with him. So those would be the three levels: the Esprit group that had to do with criticism and culture, the Malraux and Sartre philosophical group that would also include Gabriel Marcel and Merleau-Ponty, who he got to know a bit, and then these Christian intellectuals, these larger-than-life figures.

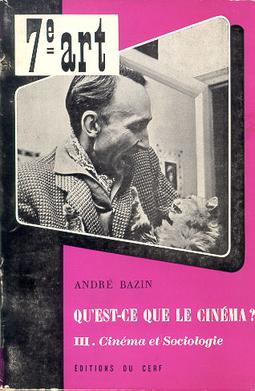

In 1944 Bazin wrote and published his first major essays on film: Ontology of the Photographic Image and The Myth of Total Cinema. In your biography you talk about these essays being seminal in understanding Bazin’s critical analysis of film history and aesthetics. Can you tell us a bit more about these essays here and how they changed the way people thought about film?

|

"The Ontology of the Photographic Image" and "The Myth of Total Cinema"

appeared in André Bazin's anthology Quest-ce que le Cinema? (What is Cinema, 1958)

|

Yes, I’ve gotten to learn a lot more since I wrote the biography. The ontology essay is actually a very special essay in his work. I mean, he wrote – you may have seen these giant two volumes of Bazin’s writings – there’s two thousand five hundred articles. There are thousands of articles, and he wrote all that in twelve years – it’s amazing. So, he had to be writing constantly. His essays are almost all like first drafts, and he’s just so good at writing down what he thinks, and it always makes sense. But for the ontology essay he spent time revising and that’s what makes it different. He’d already started on it, or something like it, in 1943, I think, and then in 1944 he did write his first version of the essay, but it didn’t actually come out until 1945. It was submitted in 44, and it was going to come out, but the publisher Tavernier, the filmmaker Bertrand Tavernier’s relative – his printing shop which produced it was raided by the French police and some of the people who were writing tracts against the government were shot, and they closed the place down. They said, we’re not going to publish this big anthology about art and cinema where Bazin’s piece was supposed to come out. So, they waited until after the war, and then it came out in a huge collector’s item of a journal, 400 pages or so, and there were a lot of great names in it. So, of course, Bazin had a lot of time to rethink his essay, and I think he just got it right. It's not quite the same as the one you’ll read in What Is Cinema? He made some changes. The first version is more radical; there are some passages that are really interesting that Bazin slightly amended later on to try to make his work maybe more academically sound. He took some chances in the first version that really accord with today’s ideas. For example, he talks about the “time of the object” in that famous passage where he talks about cinema embalming time. He says that cinema gives us the time of the object, that objects themselves have a kind of temporality that is different from human temporality, and that accords very nicely with what Gilles Deleuze would say later on. Deleuze was following Bazin, I believe, even at this time, so that in Bazin’s essay on Malraux – he published that in a little journal called Poétique which just operated during the war – two issues later there’s Giles Deleuze’s very first essay he ever published. So Deleuze would certainly have read Bazin, he would have read the journal that he was publishing in. So Deleuze was following Bazin’s way of thinking and the kind of films he liked, and I think he did it from the beginning. I find that to be a really interesting thing.

Anyway, that moves us back to the L’Espoir essay, which I think is important. I would tie the Ontology of the Photographic Image essay, which we’ve just been talking about, to The Myth of Total Cinema and the L'Espoir essay as three key essays in the first year of his career. The Myth of Total Cinema came out in a very early issue of Critique, which was the journal that Georges Bataille founded. So that gives Bazin another kind of prestige that he was there at the beginning of Critique,which became one of the most radical and important journals of that time. So, he was a young guy who had only published thirteen or fourteen pieces in little student magazines, and suddenly he was being called on to write what turns out to be an attack on Georges Sadoul’s Marxist view of the history of cinema. That’s what The Myth of Total Cinema is. There’s been a lot of discussion about that essay. It’s given me a lot of trouble actually; I still don’t claim to fully understand it. He just dashed off a film review, and suddenly everybody’s saying this is what Bazin thought for all time – but I think Tom Gunning and others who treat this essay very carefully are right to do so. I think it is important, and it does show this issue of evolution and his attachment to the idea of myth and what a myth is. And it does show, in part, both his idealism and the idea that there could be a myth, that people were so fascinated with the idea of reproducing life as it is before that could happen. They’d been thinking about that since the very first days of human civilization, but it was only later on that they began to suddenly do it. Then he also gets into the material reasons that some of these things could happen, but he does not want to have a Marxist materialist view: that it’s the machinery that is going to produce consciousness, which is going to permit these inventions to come. He thinks that human beings have always been trying to do these things, and in various ways had done it, but then there was suddenly a social need for it. So, they were both very important essays and have remained so, and he puts them right at the beginning of his own collection Qu’est-ce que le cinema?, which became What is Cinema? in English.

These essays introduced, not just Bazin’s ideas, but also his way of conveying his thoughts on the page. What makes his writing so distinctive in your opinion?

I’m translating him now, and I’m trying to translate as much as I can before I die. I’ve done a couple of volumes, and I’m doing a third one now, so I’ve gotten to know his writing closely, and it’s magnificent. I mean he does have a very classical French style, very long sentences often, but he balances his clauses in a rhythmic way – and the ideas are subordinated to each other in the perfect classical French style. He was a French major as a college student and he really learned how to write. He just had it in him to do that. So that’s the first thing. The other thing that’s more interesting, especially to people who don’t really read French, is the metaphors, which are hard to miss. His writing is packed with metaphors and analogies and, I think, these are always pertinent. I mean, he seldom uses off the wall metaphors to lighten up his text. He uses something that will actually explain the phenomenon he’s after. And believe me, it’s everywhere. Even when he’s writing the smallest little Hollywood film, or a film from Egypt, he’ll still try to introduce metaphors that will get at what is distinctive about the film, that are illuminating. Lots of the metaphors are from biology – he was very interested in biology – so I had to look up many things about molluscs, botany, entomology. He loved this stuff as a kid, and he really learned all these things. Mathematics – he learned a lot of math – so when he talks about that he knows what he’s talking about. Or calculus, when he talks about integral realism he’s talking about calculus. The same is true also for physics. Then there’s theology. He had been a practicing Catholic, and he really learned his theology and he had a couple of friends who became priests, and he would argue with them. He knew the history of Catholicism inside and out, and the various heresies and so on, and he dips into those occasionally as ways of explaining things. When he talks about Bresson, for instance, and Jansenism, he knows what he’s talking about – and that doesn’t even get into the normal references that any cultured guy would make about art history, literature, and philosophy. It’s never casual, and it’s always clarifying.

So those are the two big things: the classical style, and then this elaborate use of metaphors which he plays out throughout a text. And then maybe even more important than that to his writing is that he had a way of dealing sympathetically even with the most paltry film. I’ve got way more of a cultural hierarchy in my life than he does. Whether it was high art or low art it didn’t matter to him, and you can see that in the writing. He gave the same sort of attention to everything, and he believed in the cultural value of popular art. He couldn’t abide any condescension or laziness, so he can be rough often on Hollywood films and on commentators on television. Any time anybody looks like they’re entitled or condescending to the audience, he gets on them, and he doesn’t like any entitlement, including Hollywood thinking that they can just colonize the world. So, he really wanted to have everything, including popular culture, be ambitious and he wasn’t going to dictate what that meant. Anyway, you can find that in his writing, that he wants to write about things that he cares about. That would continue at Cahiers du cinéma by the way. They only had people write reviews who liked those movies. If someone disliked a film, they wouldn’t put that person on the review staff for that particular film.

Bazin didn’t just write about film, he was also very active in setting up cine-clubs, organising film festivals and lecturing about film at schools and factories. Why do you think he wanted to engage with audiences directly in this way?

Well, it goes back to his life in the occupation. The social nature of the medium was really important to his psychology and his way of being with other people. He also did aspire to try to make the world better. I think this comes from his Christian upbringing, and his idea of being a teacher was to enlighten as many people as he could to be curious about the world and create a better society, it’s as simple as that. Actually, the very first piece he wrote was not about cinema at all, but it was about pedagogy. He was trying to make a better system of education and better teacher training. This was partly because he had just been dumped from his candidacy to become a teacher. That made him angry, I think, and he thought there needed to be a new system. So, he was interested in pedagogy professionally at the beginning, and being a failed teacher he was always going to want to explicate things in a new way.

It is odd to think of him, with his pretty observable stutter to be so frequently in front of large audiences in workers clubs, in front of student bodies, and so on, explicating films and talking about them, but he liked to do it and he would fight right through his stutter. I’ve been able to hear him on a few things – I’ve been collecting every instance when he was recorded, there are not that many of them – and I don’t think he was that difficult to listen to. He just went through that and still wanted to engage the public, and maybe because of that stutter people tried to listen more closely to what he had to say. In any case, he always wanted to explicate while searching for what he cared about, or what he wanted to know, or what made films interesting. And I think it was part of his Esprit Christian existentialism – trying to make the world better.

|

Chris Marker |

Also, after the war he was quite involved in trying to have these meetings with German students and German intellectuals, to try to heal the effects of the war. He would go to Germany with Chris Marker, who was very similar to him. There’s a book coming out on Chris Marker’s earliest writings on film that Steve Unger has just finished editing. It’ll come out on Minnesota Press next year, and you’ll see it there. Marker was his assistant; he was his secretary. They would go together, and Marker was really interested in pedagogy and was even more committed to Esprit than Bazin. So, they had this social mission of trying to teach using film and cine-club activities to try to produce audiences that would feel that there was a common cause that they needed to make a better civilization. That is, of course, why neorealism became so important to him. It was a kind of cinema that showed the effects of the war and a whole people trying to raise themselves up out of the rubble. He loved all those movies and what they did for audiences to give them a sense of a new Europe that could be created after the fall of Mussolini. Things were a bit different in France, but it was to some extent the same, and in Germany, of course, the same. He loved the Rossellini films, and he thought of Rossellini as a kind of teacher as well. He was proselytizing for a kind of Christian democracy with love behind it that would make a new world so that the old, entrenched interests wouldn’t come back. But, of course, they did come back with the Cold War, and everything got bifurcated again between competing groups, but he by that point in the 1950s he got really sick, and he just turned inward and away from it. He would always be doing some cine-club stuff, but the cine-club stuff was really from 1944 to 1950 when he was running this Communist organisation Travail et Culture. He was running the film unit of that and was involved with all the other people that were doing it, so it was really an idealistic activity that his illness and the Cold War wrecked by 1950.

On a personal level Bazin seems to have made an extraordinary impression on many different people. Based on your research why do you think this was?

I sure wish I could have met him, so that I could have seen it myself. He’s not a good-looking guy. He’s small of stature and he’s not forceful. He never forces his own view of things, but he is rigorous in his thought and was just so feverishly intelligent that he would try to bring out what other people were thinking or trying to do. So, his discussions with Bunuel and Renoir and Rossellini were all on the level of trying to make them see what he saw in them. When he met Orson Welles on the famous night at the Venice Film Festival when Welles’s film lost out to Olivier’s Hamlet, Welles got drunk at the bar of the Excelsior Hotel, and Bazin was there with him. He stayed up with him all night, and he helped Welles recognize what he was doing. And then he wrote a book on Welles, the first book ever written on the aesthetics of a single director. It came out a year later, and I think Welles really liked that. In fact, Welles wrote me a postcard about Bazin when I was publishing my biography, so he remembered him for sure. I think it’s because he could help people realise what they were thinking, that was one of the main things.

|

|

He was also a very helpful guy. One of the things that I have learned, that has been most fun for me since I wrote the biography, was about his relationship with François Truffaut and Fernand Deligny. Deligny was a radical teacher from the north of France, and he wanted to show films to his students, so he appealed to Bazin and Marker to try to help him get a couple of films. So Bazin got him into film as part of Travail et Culture. And then Deligny came to work with Travail et Culture in their education wing, and he actually lived in the next apartment to Bazin. Deligny was a real wild man, and he would go on to become the guy who started the term “nomadism”. Giles Deleuze and Félix Guattari got many of their ideas from Deligny in the 1960s because he was running this school for autistic children in a forest. Anyway, I’m going into all this because I’m sure it was because Deligny lived next door to Bazin that Bazin decided to adopt Truffaut, because it was right while he was living next to him that Truffaut’s case came up and he was going to be sent to reform school and Bazin said, “I’ll take care of him.” And I’m sure it was Deligny who said, “Yeah, you gotta do it, you got to take care of these kids that are wild kids.” And then when Truffaut makes The 400 Blows Bazin told him, “You should talk to Deligny if you want to know how to do the psychologist scene.” And he changed the psychologist scene completely around because of his discussions with Deligny. And Deligny also counselled him to end the film by just having the kid run because that was Deligny’s idea, follow the kids. There are lots of writing on Deligny now, and you can learn more about the question of nomadism and just letting the kids run wild and just following where they go. So, the end of the film really is a Deligny kind of finish.

Anyway, that’s the long way of trying to tell you the way Bazin could both use and help people at the same time and get these interchanges going that I think people really profited from. He made things happen simply because he was so quick at understanding what might happen and was pursuing it through talking. He didn’t make movies really, he just talked and pointed people to other people and movies that he thought would assist where they wanted to go. So those are the main qualities. There was the legendary Franciscanism – he would just take time for anything, he loved animals, he loved looking at plants. He just had an intelligence that grasped on to whatever he could see. He saw inner relationships between all these things: the animal life worked in relation to the human organisms and the relationship between culture and filmmaking in relationship to the cosmos itself. I don’t know how far he went in his cosmology, but he saw everything as interconnected.

Bazin wrote in praise of many films and directors but there were two directors whose work he held in particularly high esteem: Jean Renoir and Orson Welles. Why did their work exemplify for him the kind of cinema he most admired?

|

Jean Renoir |

I think it comes down to the timing of it. He would have seen Welles’s Citizen Kane at about the same time he would have seen Renoir’s Rules of the Game. He knows that they were made within a couple of years of each other at the beginning of the war, but he couldn’t see them then. He might have had a chance to see The Rules of the Game – I don’t know if he did in 1939 – anyway, he certainly saw it after it was kind of restored in 1945. And he saw Citizen Kane and Ambersons as soon as he could. So, they came out at about the same time, and he saw that Welles was doing something else and Renoir was doing something else. And it was what I would call simply modernism, conceived of as depth and temporality. So, depth of field, being able to see relationships between things all at once happening together. And secondly temporal depth, profundity of time moving on. All of this was opposite to, and a reaction to, the clipped dramas that were made in France and Hollywood in the classical period. He appreciated those films, but he thought they had become too conventional – seven hundred shots with simple backdrops and everything clear – and he wanted something that was much more engaging and took more time. And I think he thought of depth in terms of the novel. I just finished this really good anthology on Bazin and adaptation, and I think it was more than just the fact that there were so many films that were adaptations that he had to watch. He wrote about adaptations because he really believed that the cinema was profiting from its engagement with the depth of novels. That is, the relationship between interiority and subjectivity that comes through style and its relationship to the outside world, the environment. So, he thought that the cinema was aspiring to that and was doing that, not in the simple-minded adaptations that you were getting in Hollywood, knock-offs of novels, but in the deeper way that films like Citizen Kane, which was an original drama, and Rules of the Game had done. These were novelistic films for him. They had the same kind of depth of temporality and character and subjectivity that novels did, and he thought that cinema was maturing because of them. That’s the modernist phase that he wanted to see brought together. He’d been thinking about this when he wrote these very big essays on these guys. In my introduction to the adaption book, I wrote about his understanding of a new kind of cinematographic language that he felt Renoir and Welles brought into effect. And he started a whole new vocabulary that had to do with mise-en-scène and with depth of field and traveling camera; all that vocabulary came out of his engagement with these two directors who are quite different from each other, but they respected each other. Welles said that Renoir is the greatest filmmaker who has ever lived, so he believed that. I don’t know what Renoir thought of Welles. Anyway, they were big guys, and I think Bazin used them to come to a new kind of vocabulary about filmmaking that the Cahiers du cinéma critics learned from and tried to then work out in their reviews of films and later on in their filmmaking.

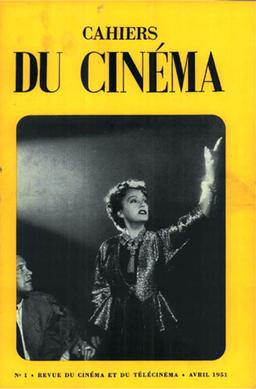

In 1951 Bazin co-founded Cahiers du cinéma. In your opinion, what role did he play in making it the most influential film journal of its time?

|

the first issue of Cahiers du Cinema |

He was there at the start along with Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, who was another guy of his age, who was also a very good aesthetic critic. They’d written together in the Revue de cinéma,which was the most high-class film journal of its time. It died in 1949, so they decided they had to resuscitate something like it. The two of them were ready to do that in 49, but then Bazin got really sick such that he pulled out of everything, and had to leave Paris. In January of 1950, he went on a skiing trip and came back wracked with tuberculosis. He had other diseases, but the TB was bad. He was in several sanatoriums and then he recovered in the Pyrenees – so he was not physically present when the first issue came out. Instead Lo Duca's name appeared as an editor. His name was used, and he was crucial evidently to the founding of the journal. In fact, he had to be one of the editors because that was the only way the backer was going to permit it. They weren’t sure that it was going to go anywhere – Revue du cinéma had died so why would this continue? But in the first three issues Bazin published two of the greatest pieces that he ever wrote. One of them was on depth of field in the first issue, and then in the third issue the magnificent essay on The Diary of a Country Priest. Then soon after he wrote the piece on the French Renoir. So, these were the anchoring pieces, and people said this is a serious journal. Well, they were reading some of the best stuff that still has ever been written on cinema. Bazin had time, being sick, to really write great pieces on fewer films. He wasn’t seeing everything during that period. He couldn’t go to the movies, he was watching TV, but he also then wrote on these major issues on films that he had seen and remembered. So, he was a kind of moral force. He was the one who the other critics were trying to use as their model. Then he brought in some of these young Turks who he had gathered around him at the Biarritz Festival in 1949. Eric Rohmer and Jean Douchet were there, and Rivette, and Truffaut who had been his secretary at that festival. He met those guys at the festival in 49. They all hung around Rohmer who was the same age as Bazin but had a different kind of authority from his. People loved Rohmer; he was a strange guy and closer to them in spirit. Bazin – they thought of him as a little bit more of a father figure, so he had that moral authority. Plus, he had the final say over what was published so he held off Truffaut for quite a while. Truffaut was living at his house. He had adopted him and gotten him out of prison, but he wouldn’t publish him for a while. He made sure everything he wrote was up to snuff. But he and Doinel Valcroz were crucial. They were the two editors that really ran Cahiers du cinéma for all those years, with Rohmer taking on a bigger and bigger role as things went along, and he would take over the whole thing when Bazin died.

You point out in your biography that not everybody has admired Bazin’s writing. He’s had his detractors who have criticised or dismissed his viewpoints, including those who took over at Cahiers du cinema in the 1960s. I wondered if you could summarise what some of their objections have been to his views?

It actually had more to do with his New Wave disciples than with him. Famously, the people at Positif were jealous of the success of Cahiers. They had a very successful periodical which was more surrealist and leftist. Cahiers was considered, and probably rightly so, to be more interested in personal freedom and the genius of creators, of youth. It had a lot of detractors from the communist party, especially during the Stalin period when people were arguing over Stalin. It was a very difficult moment. So that was probably the beginning of it.

Actually, Bazin’s most famous essay that he wrote in his lifetime was none of the ones we’ve talked about – it was The Myth of Stalin in the Soviet Cinema. It came out in Esprit the summer of 1950, right at the beginning of the Korean War. It really was a takedown of Stalin, and it was a good thing that he was out in the countryside because he had a lot of people ready to target him, because even famous people were Stalinists, people we know well. So, he was known to be anti-Stalinist and therefore, they thought, anti-Marxist. Anybody with left-wing politics – and you divided yourself up in those days and still do to some extent – went after him. His more right-wing followers – I would say Truffaut and Godard – and Rohmer was unapologetically conservative – they were writing all kinds of stuff, not just in Cahiers but also in the magazine Arts, that Bazin wrote for as well. Truffaut ran the film section of that, and the Positif people and other leftists really didn’t like it. And when the Cahiers critics started to make films, many of which had to do with the salvation of young guys, or the damnation of them by young women who were just available as sources of grace, they didn’t like it. It’s true of Breathless; it’s true of a huge number of French films. They didn’t deal with the social issues, they made everything a kind of spiritual problem, rather than a problem that could be fixed or dealt with by political and social reform. And Bazin had greatly attacked films by Cayatte and others whose films all had great moral dimensions to them, for instance Cayette’s film, We Are All Murderers,against capital punishment. Cayette had all the right political opinions, yet Bazin and his colleagues said his films are didactic, the characters are robots, and there’s no magic in them at all. Well, you can imagine that the left-wingers weren’t going to want that, so they went after him badly right away after his death when he was considered a kind of saint.

|

Jean-Louis Comolli |

Then the second wave came –you’ve already mentioned it – in 1967, 68, 69, which foundered on Rohmer’s deposition – when they knocked out Rohmer from the leadership of Cahiers and put in Jacques Rivette in 1963, who was way more modernist and left-wing. Then Rivette put in Jean-Louis Comolli and Jean Narboni, who were even wilder young guys, Marxist and Maoist. Next Serge Daney got involved and you had a whole new crew. My former student wrote a very large and brilliant book, The Red Years of Cahiers du Cinéma, about this era that was his dissertation here at Yale. It’s a great book that goes through those years in depth. Bazin had to be taken down. They wanted to reverse what the journal was all about. They wanted it to be about social revolution, and they took out pictures from the journal. Bazin was the father they had to destroy. Nevertheless, at the same time, and I’ve said this for a long while, they still adhered to his way of doing things. They still worked with close analysis, they still worked on particular films that were fertile, and they still believed in some filmmakers being way better than others. So, it’s John Ford’s Young Mr Lincoln that they go with, or Sternberg’s Morocco, or it’s Pasolini that they want to deal with. And they wanted to do symptomatic readings, opening up films from the smallest little portion of them, which Bazin had learned to do and taught his followers to do. And they wanted to go after big ideas like Bazin had done, but maybe of a different sort. Finally, they also had a kind of hierarchy, an auteurism that resulted in a list of which filmmakers were better and worse.

There was the famous article by Narboni and Comolli on the ideological levels that films can have, A through F, with each one being classified as to whether the filmmaker belonged in a higher or lower rank, given its relationship to politics of form and politics of content. Well, Bazin didn’t do that, but he did want there to be discriminations among filmmakers for different reasons. So, yes, they went after him, but went after him in a way that I think held him up. Maybe the best example of that is the articles that Serge Daney and Pascal Bonitzer wrote about Bazin’s concerns with death, the wonderful pieces in 1971 where they’re trying to get up a psychological basis of Bazin’s beliefs about cinema. So, while they’re disagreeing with Bazin about what films should be about, they’re recognising in him something really remarkable about the cinema and its relationship to death. I’m very proud that when the translation of my biography came out in 1984, Daney wrote a really nice review. He talked about Bazin’s importance, and he became the second Bazin. He wanted to stand on his shoulders.

Bazin has been described as the father of the French New Wave. How important, do you think, was his influence on the New Wave directors and their films?

|

Truffaut and Rossellini |

You know, I’m not sure he was as important as people like to make him out as. The main thing was he gave those people the ambition to try to lift cinema up out of something which was ordinary and try to do something remarkable and maybe a bit more in the realm of what the novel could do. Also, his attitude toward documentary and toward the realist basis of cinema was really crucial, and here he did it through intermediaries like Jean Rouch and Roberto Rossellini. In 1954 and 1955, Truffaut and Godard were meeting with Rossellini and Rouch. There were great meetings that have been described between these figures, and both of those directors worked for Rossellini. They were really influenced by Rossellini and Rouch, and they met at Bazin’s house on some occasions. It was through Bazin that they really got to appreciate and admire these guys.

Also, Bazin’s insistence that cinema wasn’t just a fictional art, but it had this surplus of recording stuff, I think, would definitely mark all of them, especially Godard, but also Truffaut and Rivette. The idea that the camera recorded things that you didn’t even intend to be there – and there was a kind of fight between its ability to just kind of naturally ingrain things on celluloid and a director’s imaginative desire to say something fictional. That fight would produce some of the most interesting films, like Rouch’s Moi, Un Noir, a fictional film made by real people in Africa that is auto-cinematic – a cinema that produces itself. Godard said that was his favourite film of the year 1958. Bazin died that year and in his last piece, a review of Chris Marker’s Letter From Siberia, he held out that question of documentary and fiction and the essay film, the intelligence that could go into a film, including voice over and sound, that mix that he thought of as impure cinema. I think he really helped make the New Wave the cauldron in which different kinds of recipes could be thrown in, and new things would come out, including from the more shellacked pieces of the cinéma de qualité which he had some respect for, but which had run its course as far as it could go.

Finally, I wondered if you had a favourite Bazin article or articles that you would particularly recommend that people read?

This could go on a long while. Firstly, of the great ones that people know, I would just underline The Ontology of the Photographic Image, which repays really close attention, especially if you can read it in French. There’s a couple of different versions of it. There’s the new Timothy Barnard translation of it which is more accurate in a lot of ways but more bloodless. With the help of a colleague, I have remastered a couple of Hugh Gray’s quite beautiful but often inaccurate translations in What is Cinema? I did this in André Bazin on Adaptation, the anthology I just put out, where you can read a better version of Gray's translation of Bazin’s Impure Cinema essay, which is another great one, and also find Cinema as Digest, which is his first run at adaptation theory. There are some great metaphors in it.

|

Diary of a Country Priest |

I also recommend the essay on Diary of a Country Priest, which we also reworked from Hugh Gray’s beautiful but often flawed translation. Gray thinks it’s the greatest essay ever written on a movie, and it could be. It’s really an amazing piece. Of the pieces that are less well-known, I like the two on actors a lot: The Death of Humphrey Bogart, which is really great, and then The Destiny of Jean Gabin, maybe less great but more interesting for people who love French cinema – that’s still a very important piece. And then I would point to A Bergsonian Film: The Mystery of Picasso after the Henri-Georges Clouzot film. That has some of the deepest philosophical things he ever said and that’s usually available.

Now a couple of ones that are less well-known, in addition to Death Every Afternoon about the film by Braunberger, which is often cited, there are odd ones like The Entomology of the Pin Up Girl, which is an early piece that reminds me of Roland Barthes’s Mythologies. He wrote it when he was very young about the time he wrote The Myth of Total Cinema, and it’s fun – it’s a small piece that shows he can be really playful. He also wrote one called It Snows on the Cinema. I love the title Il neige sur le cinema about snow scenes in films. It gets into his meteorology: cinema is like crystals of snow – images are like crystals each one is different, and there is a kind of frozenness about the celluloid. It’s not his best, but I love it. One that has been held up a little lately because it was reprinted somewhere, I think in Film Comment, is Every Film is a Social Documentary, which shows the reach of his social concern about cinema. He says that you should watch every film because you can do something with it. In it he’s talking about ideology theory really, so he does have some of the ideas that would come up later that he’s usually accused of not countenancing. I concluded André Bazin’s New Media book, in which I translated fifty-five or so essays of his writings on television and cinemascope, with a piece that I found remarkable, called Is Cinema Mortal? And it’s so relevant. He’s asking this question in 1952/53: is cinema mortal? And he says that yes, cinema is mortal, it’s going to die. Regular arts don’t die – theatre, music and poetry, painting – they can’t die because they’re part of the human body. People just do that stuff for each other. But cinema is a technological art: it’s going to die as technology changes, and he’s not against it. It’s a very interesting piece. There’s many more, almost two thousand five hundred of them, and they’re almost all worth looking into.

Dudley Andrew’s writings that feature the work and life of André Bazin

BOOKS

André Bazin Oxford University Press, Enlarged edition, Oxford, 2013. First published 1978; enlarged edition Columbia Univ. Press 1990. (French, 1983; Chinese, 2011; Turkish 2013, Korean 2020, Japanese 2022)

What Cinema Is! Bazin’s Quest and its Charge. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. (French 2014; Farsi 2018, Arabic 2018; Chinese, 2018, Turkish 2019)

Opening Bazin (edited with introduction), Oxford Univ Press (Winner SCMS best Anthology Award for 2011) French version ed by H. Joubert-Laurencin, Ouvrir Bazin (Edition de l’oeil, 2014)

André Bazin’s New Media, 57 essays edited, translated, and introduced (U of California Press, 2014)

André Bazin on Adaptation, Cinema’s Literary Imagination, (edited with introduction (Univ of California Press, 2022)

ARTICLES (chronological order)

“Cinema and Creative Community” in Cinema, Media and Human Flourishing, ed by Timothy Corrigan (Oxford, 2023)

“Love of Community and Reality: On André Bazin and the Good of Cinema” in J. Hanich ed. What is Cinema Good For? (Univ. of California Press, 2023)

“The Effect of Miracles and the Miracle of Effects: Bazin’s Faith in Evolution,” in M. Lefevre (ed) Special Effects on the Screen (Amsterdam University Press 2022)

“Bazin, Barthes, and Ecriture,” in Di Leo (ed) Understanding Barthes, Understanding Modernism (Bloomsbury, 2022)

“Andre Bazin” Oxford Bibliographies: Cinema and Media Studies. 12000 word annotated entry, 2018, updated from 2012.

“Dark Passage into the Mystery of Being,” in Pomerance and Palmer (eds) Thinking in the Dark (Rutgers 2015).

“Bazin’s Line of Thought: Cinema as Conduit” Addresses and Papers, Beijing Film Academy, 2015.

“André Bazin and his ‘Ontology of the Photographic Image,’” in Branigan and Buckland (eds) Encyclopedia of Film Theory (Routledge, 2013)

“The Second Life of André Bazin,” preface (42 pages) to new edition of Andrew, André Bazin (Oxford, 2013).

“Seeing through the Frames of Art: Renoir seen through Bazin,” in Vincendeau and Philips Companion to Jean Renoir (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).

“Every Teacher Needs a Truant: Bazin and Truffaut,” in Andrew/Gillain, Companion to Francois Truffaut (Blackwell, 2013)

“Malraux, Bazin, Benjamin: a Triangle of Hope” in Dalle-Vacche (ed) Art, Film, New Media (Palgrave, 2012)

“Bazin Phase 2: Die unreine Existenz des Kinos,” in Montage AV, 18, no. 1 (2009) Also in Russian (2011)

“The Ontology of a Fetish,” Film Quarterly, 61, no. 4 (Summer 2008), 62-67. French translation in Trafic 67

“Foreword,” to André Bazin, What is Cinema? vol II (Univ. of Calif Press, 2004).

"André Bazin" in The Encyclopedia of Aesthetics (1998)

"André Bazin's Evolution," in Peter Lehman, ed. Defining Film Theory (Rutgers Univ. Press, 1997)

"Bazin Before Cahiers," Cineaste XII no 1, 1982, pp. 12-18.

"Andre Bazin," Film Comment March/April 1973, p. 64-69.

SHORT PIECES AND BOOK REVIEWS

“The Return of Classical Film Theory” a roundtable with D. Andrew, Annette Michelson, et al. October (Spring 2014)

“La Second Vie d’André Bazin” in Cahiers du Cinéma, February 2014.

Preface to Ouvrir Bazin (French edition of Opening Bazin, Paris: Ed de l’oeil 2014)

Preface to French Edition of What Cinema Is! (Une Idée du cinéma, Brussels: SIC 2014).

Review of What is Cinema? newly translated by Tim Barnard, CinemaScope, Winter 2010 (with P. Younger)

“The Godfather, André Bazin after 50 years” in Film Comment Nov-Dec 2008.

rev. Andre Bazin, What is Cinema? in Film Comment Spring 1968.

Interview by Simon Hitchman, © November 2023 - please do not reprint or reuse without permission. |