|

Jean Seberg: Breathless by Garry McGee

Well written, highly praised account of Jean's rise from smalltown Iowa girl to Paris "it" girl. Also documents the FBI's campaign against her and her mysterious death. Definitive and entertaining.

Explore this book:

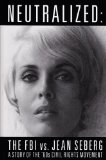

Neutralized: the FBI vs Jean Seberg by Jean-Russell Larson & Garry McGee

A detailed account of Seberg's civil rights activities, the FBI's vigorous campaign against her, their attempt to defame her, and her mysterious death.

Explore this book:

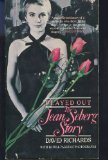

Played Out: the Jean Seberg Story by David Richards

Older biography with loads of photographs. We haven't read it, but Vincent Price says it's "superbly written" and at $2.25 on US Amazon, you really can't go wrong. If you read it and like it, let us know and we'll put your review here!

Explore this book:

Diana: The Goddess Who Hunts Alone by Carlos Fuentes

There is a reason why the French cover of this fictional novel, by acclaimed Mexican author Carlos Fuentes, bears the image of Jean Seberg. Although it is a work of fiction, the main character, and many of the things that happen in the book, are closely modelled after Jean's own life -- and, most centrally, her alleged affair with Fuentes himself. The novel takes place in the 60s and is graced by appearanced by William Styron and Luis Bunuel,among others. Highly praised by critics - it is an intriguing work of serious fiction about actress whose life was more mysterious than the plot of any bestseller.

Explore this book:

|

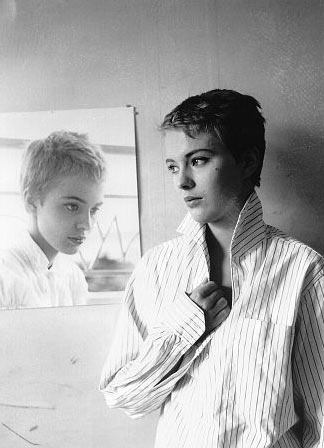

Jean Seberg (November 13, 1938 – September 8, 1979) was a small town girl from the midwest who shot to stardom at the age of 19 in the title role of Otto Preminger’s Saint Joan. Her most iconic screen appearance came two years later when she starred in Jean-Luc Godard’s groundbreaking New Wave classic, A bout de souffle. Despite her success she had a turbulant private life and tragically committed suicide in Paris at the age of 40. |

|

|

actress Jean Seberg

|

|

Jean Seberg was born in Marshalltown, Iowa in 1938, the second of four children born to Ed Seberg, the town pharmacist, and his wife Dorothy. Marshalltown was a quintessential mid-western American town whose adult inhabitants were, according to Jean, “grim, kind, dried up people who were afraid to open up.” In this church-going, conservative community, young people were expected to conform, but from a young age Jean was different. She loved books and would happily retreat into her room all day to read and write poetry. She was also unusually sensitive to the plight of animals and would often bring home stray cats and dogs. At the age of fourteen she applied by mail for membership in the Des Moines chapter of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People). Her school-friend Hannah Heyle later recalled: “Jean had a very strong idealistic streak. Joining the NAACP was just another instance of her being different. She probably didn’t understand the philosophy behind it, but she certainly loved every little living creature.”

One of Jean’s favorite activities was visiting the cinema. When she was 12, the local movie theatre screened The Men starring Marlon Brando. After seeing the film, Seberg walked out of the cinema feeling “strangely shaken.” Brando’s ability to convey emotion through his performance was unlike anything she had seen on screen before. She made up her mind that she wanted to become a famous actress. One person who took Jean’s aspirations seriously was the high-school drama coach and speech instructor Carol Hollingsworth who gave the student what she called her DDT lecture (acting requires drive, determination and talent). Jean soaked it all up avidly and from then on her course was set. Before long, under Hollingsworth’s guidance, Jean was entering oratorical contests and One Act play competitions. In her senior year, she was cast as the lead in the school production of Sabrina Fair. Performing in front of a thousand spectators at the Marshalltown High auditorium, Jean proved herself a natural on stage. “Most of us knew then,” recalled Stephen Melvin, her high school music teacher, “that if she really wanted to pursue an acting career, she could make it.”

After Jean’s graduation in 1956, Carol Hollingsworth arranged for a scholarship enabling her to take part in a season of summer stock theatre in Cape Cod. Jean’s parents were reluctant to let her go, but were reassured by her promise that after the summer she would enrol at Iowa State University. In summer stock Jean was cast as the female lead in William Inge’s Picnic opposite an actor called John Maddox with whom she fell in love. Together they planned to secretly move to New York and study acting at the revolutionary Actors Studio where Jean’s idols Marlon Brando and James Dean had studied “the method”. But before the summer was over, fate intervened when Hollywood director Otto Preminger announced in a cinema trailer that he was undertaking a world-wide talent search for an unknown actress to play the lead in his film adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s play about the life of Joan of Arc. Initially Jean dismissed the contest as a gimmick, but her drama teacher successfully persuaded her to send in an application.

Originally from Austria, Otto Preminger began his career in the theatre before establishing himself in Hollywood after the war directing popular film noir mysteries such as Laura (1944) and Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950). By the early 1950s he had become an independent producer/director with a reputation for adapting high-profile plays and novels such as The Moon Is Blue (1953) and The Man With the Golden Arm (1956), both of which challenged the restrictions of the production code censor. Any film with Preminger’s name attached was guaranteed to draw attention and Saint Joan was no exception. Jean was one of 3000 hopefuls to make the first cut and the offer of an audition after an initial 18,000 actresses submitted applications.

Jean’s audition took place in Chicago on September 15, 1956. Dressed in black, she waited in line with the other candidates, before stepping onto the stage to perform her prepared speech. Preminger later admitted that “something clicked” as soon as he saw Seberg. She had the combination of innocence and strength he was looking for. “She was a vital young woman and she had great personality. And she was very anxious to play the part,” he later commented.

Jean was asked to attend a final screen test in New York the following month. While waiting she memorized Shaw's play in its entirety. Two weeks before the test Preminger asked Jean to come to New York to prepare. It was now between her and two other candidates for the coveted role. Preminger was furious when he started working with Jean, believing her to have over-prepared. On the day of the test he drove her mercilessly, insulting her and forcing her to repeat difficult scenes over and over. “What's the matter don't you have the guts to go on?” He goaded Joan. “I'll rehearse until you drop dead,” Joan responded defiantly. By the end of the afternoon she was sobbing on the floor. Preminger encircled with his arms and assuring her that the test had gone wonderfully. Later that evening he informed her she had got the part.

Preminger’s announcement of his new discovery on October 21st, 1956 was orchestrated for maximum publicity. The day began with a press conference in the United Artists’ offices. That evening he presented his find to the nation on The Ed Sullivan Show. Jean was the girl who “captured lightning in a bottle,” Sullivan announced, before the young actress stepped out into the spotlight to re-enact her audition scene before 60 million viewers. The story of Jean’s discovery, with its echoes of Hollywood’s Golden Age, captured the imagination of the public. Her small-town origins were an essential part of her appeal and a source of pride for Marshalltown who organised a parade to celebrate her return. The town’s High School even held a special assembly in her honour during which they announced the inauguration of an annual Jean Seberg Award for most promising young actor or actress.

Saint Joan began filming at Shepperton Studios in England in the winter of 1956/57. From the moment she arrived in London, Preminger controlled every aspect of Jean’s life. He kept her isolated from the outside world at the Dorchester Hotel and made sure all her free time was taken up with preparatory tasks for her role, including intensive elocution lessons and hours of horse riding. On set she found herself working with some of the finest actors of the English theatre and felt overwhelmed. Preminger, according to some observers, was using a form of psychological warfare to elicit from Jean the performance he wanted.

On set the director pushed Jean through dozens of takes until she became confused, often in tears. Some of the other more experienced actors on set were shocked by the way Preminger was treating the inexperienced actress. The climactic scene of Joan’s burning at the stake was scheduled for the final week of shooting. With Jean chained to the stake, the pyrotechnic effects were ignited but something went wrong. “I’m burning,” Jean yelled, breaking free from the chains, curling up in a ball and covering her face. The actor playing the executioner swooped down, picked her up, and took her to her dressing room. Privately Preminger felt badly but publicly he said this was the kind of accident a director like him dreamed of. “We got all of it on film. The camera took 400 extra feet. The crowd reaction was fantastic. I’ll probably use some of it,” he boasted. Jean’s stomach would be scarred from the burns for the rest of her life.

Despite his frequent criticisms, Preminger developed a grudging admiration for Jean’s strength under pressure. Towards the end of filming, he informed her that he had bought the rights to Françoise Sagan’s best-selling novel of adolescent ennui Bonjour Tristesse, and he wanted her to take the starring role. A grateful Jean returned to Marshalltown where she worked on her French studies, took swimming lessons and caught up with old friends whose lives now seemed impossibly remote from her own.

Jean returned to France at the start of May for the premiere of Saint Joan at the Cannes Film Festival. It was a glamorous affair that temporarily overshadowed the festival itself. However, the critical notices for the film that followed were largely negative. Preminger reacted by sending Joan out on a 27-day-tour of 12 cities in the US and Canada but the reviews didn’t improve. The consensus was that Jean had been miscast. The Time magazine critic wrote: “Actress Seberg, with the advantage of youth and the disadvantage of inexperience, is drastically miscast. Shaw’s Joan is a chunk of hard bread, dipped in the red wine of battle and devoured by the ravenous angels. Actress Seberg, by physique and disposition, is the sort of honey bun that drugstore desperadoes like to nibble with their milkshakes.” A year after its release the film’s world-wide box-office gross amounted to less than $400,000.

Feeling bruised and rundown, Jean fled to Nice in the South of France where she rented a one-room apartment and soaked up the bohemian atmosphere of the Riviera in preparation for her role in Bonjour Tristesse. She was to play Cécile, a young woman who comes between her rich playboy father Raymond, played by David Niven, and a family friend, Anne, played by Deborah Kerr, inadvertently causing a tragedy. Once filming got underway later in the summer, Jean discovered that Preminger had by no means mellowed in his attitude. His behaviour on set was as tyrannical as ever, and more often than not he took out his frustration out on her. On one occasion he forced her to redo a scene in which she had to be doused in water countless times. Each time he found something else to criticise. Shivering less from the chill than from the verbal abuse, Jean carried on until she was near the point of fainting. When the company moved down the coast to film at the Carlton hotel in Cannes she had hit such a low, she later confided in a friend, that she stood on the balcony and seriously considered throwing herself off the edge.

Yet, despite such moments of despair, Jean was growing in confidence as an actress and beginning to find herself as a person. In a break during filming, she met and fell in love with François Moreuil, a 23-year-old lawyer with ambitions to become a film director. Charming and self-assured, Moreuil knew all the best places to go and all the most stylish people. Against Preminger’s wishes they began to see each other in secret. Under Moreuil’s influence, Jean began to stand up for herself and fight back against Preminger’s bullying.

Production of Bonjour Tristesse was wound up in the autumn of 1957 at Shepperton studios in England. In the final scene, Jean’s character sits at her make-up table and applies a layer of cold cream to her face. Preminger instructed her he wanted her totally expressionless as the tears welled up in her eyes. He reshot the scene all day before he was satisfied. It was a fitting end to their strained relationship.

Jean and Moreuil travelled to Paris to meet his family. Jean was now free to enjoy her private life, but professionally she was in limbo. Preminger still held her under contract but he was no longer interested in making movies with her. In December Jean and Francois flew to New York, where they sublet an apartment on the Upper East Side. The Bonjour Tristesse premiere was held at the Capitol Theatre in New York on January 15, 1958. In contrast to Saint Joan, the opening night was distinctly low key and drew few celebrities. Though, again, the critical response was hostile. “Preminger, apparently, has not succeeded in convincing Miss Seberg,” wrote the reviewer for The Saturday Review, “that she is an actress.”

Jean had failed in her second try for stardom and at nineteen she appeared to be washed up. One of her New York friends at the time commented, “She really thought that Preminger was going to wave the magic wand. And it hadn’t turned out that way. There was this terrible gap between what she wanted to accomplish and what she had actually done.” Even Jean’s attempts to gain confidence by studying at the famed Actor’s Studio under Lee Strasberg came to nothing. When she asked to sit in on some classes, he suggested she write formally. She did so three times, but never received a reply.

In France the reaction to Bonjour Tristesse was somewhat warmer. The magazine Cahiers du cinéma put her on its February cover. Inside its covers, the famed young critic François Truffaut wrote:

When Jean Seberg is on the screen, which is all the time, you can’t look at anything else. Her every movement is graceful, each glance is precise. The shape of her head, her silhouette, her walk, everything is perfect… Jean Seberg, short blonde hair on a pharaoh’s skull, wide-open blue eyes with a glint of boyish malice, carries the entire weight of this film on her tiny shoulders. It is Otto Preminger’s love poem to her.

Although, in interviews, she laughed off the untrue rumours that she was having an affair with Preminger, it was clear to those closest to her that the professional relationship with the director was hurting her more than it was helping her. He had made her famous but his dictatorial method and the critical response to the films they had made together had crushed her confidence. François decided to do something about it. He contacted Preminger and worked out a deal to sell her contract to Columbia Pictures.

In September 1958, Jean and François were married in Marshalltown. Afterwards they honeymooned in St. Tropez where they joined the social whirl around Roger Vadim. In the autumn, the newlyweds moved into an apartment in the fashionable Paris suburb of Neuilly. The marriage, however, was shaky from the start. François liked to go out every night to nightclubs with friends, while Jean, still struggling with the language, felt like an outsider.

In November Columbia put her to work in The Mouse that Roared, a cold-war satire about a tiny country that declares war on America. Filmed in England, the film was essentially a vehicle for the talents of Peter Sellers with Jean relegated to the role of love interest (unexpectedly the film was a major success when released at the box office the following year).

In the months that followed, Jean felt increasingly alienated in her new life. In a later interview she commented, “The shock was greatest because I had divorced myself from life in Iowa. My girl friends had married and led lives that I no longer had any touch with. I was a stranger everywhere. It was as if I had been completely wiped away with a cloth, and I had to begin again to re-create myself.”

She decided to find herself in her work, and with the support of her new studio and without her husband, she travelled to LA to take acting classes with the Columbia acting coach Paton Price. Price believed that the camera revealed so much that trying not to act should be the objective. He helped Jean to regain her self-esteem after her experience with Preminger and throughout her life she would return to him for artistic advice and emotional support.

While Jean was away taking acting lessons in America, a revolution was taking place in the French film industry. Working on low budgets, a new generation of young filmmakers dubbed the Nouvelle Vague in the press, were breaking conventions to tell contemporary stories in an inventive, improvisational way. François, still employed in a law firm, was caught up in the excitement. Determined to become a director himself, he succeeded in meeting a number of those in the New Wave circle, among them Jean-Luc Godard.

Like François Truffaut, Godard had been impressed by Jean's performance in Bonjour Tristesse and was interested in casting her in his debut feature film. He had no script to offer but he did have a basic story and an abundance of unconventional ideas. The short scenario, written by Truffaut, was inspired by a true story about a motorcyclist who killed a policeman and then hid out with his girlfriend who eventually informed on him. Godard saw the story as way to pay homage to the classic American film noirs he loved, as well as depicting a new generation of rootless youth. He had already cast ex-boxer Jean-Paul Belmondo in the role of the would-be gangster and wanted Jean to play his girlfriend Patricia Franchini. The film would be called À bout de souffle (Breathless).

François managed to persuade Jean to meet the unknown director despite her misgivings. She found Godard to be "an incredibly introverted, messy-looking young man with glasses, who didn’t look me in the eyes when he talked.” The seriousness with which he talked about the cinema, however, intrigued her, so she agreed to think about it. Eventually, after much encouragement from François and Belmondo, she finally consented.

Once Seberg had agreed to be in the film, Godard sent a twelve-page telegram to the casting department of Columbia in which he offered the studio either $12,000 for Jean’s services or half the worldwide profits of the film. At the same time François flew to LA and informed Columbia execs that he would take his wife away from the cinema forever if permission was denied. Columbia accepted the terms and gave their permission.

Filming began on August 17, 1959. Every day Godard would show up with a sheaf of crumpled papers, which was the closest he got to a traditional screenplay. Often when he ran out of ideas the day’s shooting stopped. As it was shot without sound (it would be dubbed later during post-production), Godard would shout instructions from behind the camera to the actors or feed them dialogue while the camera was rolling. After two weeks Jean wrote to Paton Price, “I’m in the midst of this French film and it’s a long, absolutely insane experience—no lights, no makeup, no sound! Only one good thing—it’s so un-Hollywood I’ve become complete unselfconscious.”

Despite her misgivings, Jean enjoyed what she later described as “a distant but passionate” working relationship with Godard. And she particularly liked working with Belmondo, who she described as “one of the freest actors I’ve ever worked with.” Their rapport was particularly evident in the film’s bedroom scene shot in a left bank hotel room, in which the two circle each other playfully, improvising dialogue that would soon become part of movie myth.

By mid-September filming was complete. From the rushes she viewed, Jean concluded that the movie was “bizarre but interesting,” but she wondered whether it would ever be shown commercially. It appeared to be a curious interlude in her career but nothing more.

Later in the fall, Columbia summoned Jean back to Hollywood to appear in Let No Man Write My Epitaph, a crime drama directed by Philip Leacock. She went alone, leaving François behind in Paris. By now it had become clear to Jean that she had married for all the wrong reasons. François had been the charming friend she needed when she was at her most vulnerable but their temperaments were simply not compatible. He thrived on the casual conversation of the party circuit; she yearned for intense emotional connection. He resented her mood swings and obsession with her career, while she had come to suspect his real intentions.

In LA Jean began work on Let No Man Write My Epitaph, but the slow pace and conventional methods of the studio production left her uninspired after the experience of making Breathless. During filming she went to a party at the French consulate. The Consul General was an urbane forty-five year old diplomat named Romain Gary. Born in Lithuania, Gary had served in the French Free Airforce during World War II. After the war, he had gone into law while writing novels on the side, including the acclaimed Roots of Heaven, which won the Prix Goncourt prize. In 1956 he was appointed Consul General in Los Angeles where he moved with his wife, the English writer Leslie Blanche. Jean was immediately captivated by Gary. He, in turn, was charmed by her naïveté and idealism. Within a few weeks of meeting they were having a secret affair.

In the spring of 1960, Jean returned to Paris. She and François had now agreed to a separation. As a gesture in parting, she agreed to star in his directorial debut which was due to shoot in the summer. Meanwhile Gary went on temporary leave from the diplomatic service that spring and also returned to Paris. Officially he said this was so that he could devote more time to writing, but unofficially it was to spend more time with Jean.

Jean’s private life became increasingly difficult to hide after the March release of Breathless. The film was a surprise success, provoking critical discussions and excellent box office at the cinema. Overnight, Jean-Paul Belmondo became one of the leading stars of French cinema, and Jean was recognised as a serious actress at last. More that that she became an icon to French youth for whom she represented the epitome of modern liberated womanhood. Suddenly her image was everywhere, on magazine covers and billboards. Girls began asking hairdressors for ‘la coupe Seberg’— the close-cropped hairstyle that was her trademark. Her look became the new ideal. Suddenly she was in demand and directors everywhere wanted to work with her.

For Jean, however, fame came at a cost. With the French press following her every move, she began to feel her life was no longer her own. This was particularly difficult given that she was seeing another woman's husband. The pressure mounted until one night she became hysterical and began smashing things up in her apartment. François drove her to the American hospital where doctors had to give her an injection to put her to sleep. It was agreed that she should return home to Marshalltown for a period of rest and recuperation.

Jean arrived home on April 20th. Over the following weeks she found solace in simple activities like spending time with her family and going for long walks. She also admitted to her parents for the first time that she was getting a divorce. This interlude could not last long as filming of François’s film was to begin on the 6th of June. Fearful of returning to Paris, Jean convinced her grandmother to accompany her. They arrived in the city on June 3rd and checked into a Paris hotel three days before filming was due to start.

La Récreation (Playtime), which Moreuil had based on a short story by François Sagan, was the first of three films Jean had lined up back to back. All of them would showcase her image as the quintessential free-spirited American abroad.

After La Récreation, she was to star in Les Grandes Personnes (Time Out for Love) for director Jean Valère. Following that, Philippe de Broca had cast her for his comedy about adultery, L’Amant de Cinq Jours (The Five-Day Lover).

As Jean had feared, the filming of La Récreation was turbulent. The couple put on a united front for the press but once the reporters had left tensions rose to the surface. Because her participation had been instrumental in securing financing for the film, Jean later referred to La Récreation as her “farewell present to Francois.” Privately she described the two months filming as “pure hell.”

In Les Grandes Personnes (Time Out for Love), Jean played a nineteen year old girl from Lincoln, Nebraska, who travels to Paris and falls in love with a jaded playboy who races cars for kicks. Once again Jean’s innocence is contrasted with the jaded world-weariness of the locals. “I’ve always thought of her as Alice in Wonderland,” said Maurice Ronet who co-stared with her in the film and would go on to make three other films with Jean. “She had the same delighted astonishment at everything she saw and everyone she met. Even when things got bad for her, she kept that openness. She was always a kind of Alice for me. Even at the end, when she was Alice in Horrorland.”

By October, Jean had begun work on The Five Day Lover. In order to distinguish her from her previous film roles, director Philippe de Broca had her wear a brown shoulder length wig. It was an inspired choice and helped Jean give one of her best performances. She plays Claire, a married English woman with two children, who has an affair with a charming gigolo. “Life’s a bubble. When it touches the earth, it’s over,” her character says at one point. It’s a line that sums up the film’s combination of comedy and melancholy. The Five Day Lover would receive glowing reviews when it was released in America the following year and was one of the few films that Jean remembered with affection later in life.

At the end of 1960, Jean and Romain moved into an elegant apartment on the Rue de Bac, a stone’s throw away from the fashionable Boulevard St. Germain. Jean enjoyed a busy social life amongst artists and musicians with whom she shopped, visited museums and art galleries, and went to jazz clubs. Jean and Romain were still not admitting publicly to their affair but speculation continued in the press. To avoid it, Jean set off on a six-week tour of the Far East at the invitation of the Japanese film industry. While she was away her film star status was confirmed when her three new films opened within ten days of each other in Paris. It led one journalist to declare it a Jean Seberg festival. Though the films received mixed reviews, critics were unanimous in their praise for Jean. Her innocence and charming American-accented French, which had proven so popular in Breathless, continued to captivate cinemagoers.

Jean's next film role was in a Franco-Italian co-production called Congo Viva, in which Jean was cast as the disillusioned wife of a Belgian colonist who drifts into an affair with a journalist. On September 6th Jean departed for Leopoldville, capital of the Belgian Congo, which had recently gained its independence. Filming on location proved exceptionally difficult. The heat was oppressive and a number of cast and crew, including Jean, came down with dysentery. Then a civil war broke out in the country forcing the production to relocate to Rome. Gary joined Jean there, but the Italian press proved even more intrusive than their counterparts in Paris.

Inevitably, the rumours about Jean’s ménage a trois reached her hometown when a journalist working for the Des Moines Register, drawing on French newspaper gossip columns, wrote an article titled “Jean Seberg, idolized, is saddest American.” The article portrayed Jean as a disillusioned home wrecker who was cheating with another woman’s husband. Its publication also happened to coincide with the debut in the mid-west of Breathless, which only reinforced the image of Jean as an immoral person with no sense of loyalty. The news story was highly uncomfortable for Jean’s parents, who were forced to weather the disapproving gossip of their neighbours. For Jean, who always craved her parents’ approval, this was highly upsetting, particularly as she was now hiding from them the fact that she was pregnant with Romain Gary’s child.

Jean’s son Alexander Diego Gary was born secretly in the summer of 1962 in Barcelona. Jean spent the last months of her pregnancy in the Spanish city in hiding. For the first years of his life Diego was kept from the public eye and even some of Jean’s oldest friends were unaware of his existence for several years. Her parents had no idea. She hid the truth because she feared, with some justification, that the resulting scandal could derail her career just when it seemed to be back on track. Columbia had put Jean forward to star in In the French Style, a prestigious production to be directed by Robert Parrish, in which she was to play an American girl in Paris who becomes increasingly disillusioned as her heart is broken by a series of unreliable men.

Leaving the baby in the charge of a governess, Jean reported for filming in Paris in late August. In the French Style was, in effect, a summing up of all the naïve American girl in France films Jean had made up to that point. Reviews were mixed but the film made a modest profit, and Jane’s performance received some praise. Director Parrish later observed: “She really had absorbed an amazing amount of knowledge about the art of filmmaking for one so young. On top of that, just for sheer beauty on screen, she was a joy to photograph. She was great for a camera—she acted with her eyes and mouth, all the things that are suited to close-ups. It was an up time in her career. She really pitched in and worked harder than anyone else.”

In January 1963 Jean reunited with Jean-Luc Godard who was one of five international directors who had been asked to contribute a sketch to a film entitled The Greatest Swindles of the World. In Godard’s Le Grand Escroc (The Big Swindler), Jean again plays Patricia Franchini, four years on from Breathless, and now a reporter for a San Francisco television station. The story takes place in Morocco where Patricia interviews a counterfeiter whose idea of charity is to give out fake money to the poor. Filming took place rapidly in Marrakech but the sketch was deemed by the producers to be the weakest of the five and dropped from the final film.

Shortly after arriving back in Paris, Jean learned that the acclaimed director Robert Rossen was interested in casting her for the starring role in Lilith, which he was adapting from J. R. Salamanca’s novel for Columbia. The story explores life in an exclusive mental hospital, and the attempts of a young schizophrenic woman to entrap a well-meaning orderly named Vincent in her self-destructive game-playing. Warren Beatty had already agreed to play Vincent, but the key role was Lilith herself, the troubled young woman he tries to help. Several actresses had already been considered for the role, including Natalie Wood, Samantha Egger, Sarah Miles and Diane Cilento, but Columbia wanted Jean. Rossen flew to Paris with Beatty to meet her and agreed to give her the part, explaining to the press: “Lilith is not a villainess. She’s too much good gone bad. It’s usually innocence that makes the sharp transitions to these psychotic stages, and it’s the innocence that attracts Vincent. I think Seberg is just right for it. She’ll be great. She’s got the flawed American girl quality – sort of like a cheerleader who’s cracked up.”

Entrusting Diego to his nanny again, Jean travelled to New York at the beginning of April 1963 for pre-production work. As part of her preparation she met a number of women in mental hospitals. Some of her friends noted how much the experience had touched her. One observed, “She was very deeply marked by the experience. All these young people her own age with these incredible problems – she couldn’t forget it.”

On set, Rossen gave very little specific direction to the actors. Prior to filming each scene he would describe the intellectual and psychological states of the characters to the actors, then allow their creative imaginations to guide them. Jean thrived on this approach but Beatty felt he was being sidelined, causing tension on the set. Filming overran on into August, leaving Jean emotionally exhausted. She had dug deeper within herself — more than any of her other roles — to play Lilith. It was, in a sense, a journey of self-discovery. As one friend remarked, “There are times in that film when what you see on the screen is Jean herself – pure and unadulterated.”

When Lilith was released the following year Jean's performance got some good reviews but the film was widely panned and very few went to see it. This was very disillusioning for Jean who had put so much of herself into the role. She defended the film all her life, citing it as her finest work.

On October 6, 1963, Jean and Romain Gary were secretly married in Corsica. The celebrity couple enjoyed a busy life in Paris. Jean now had a live-in maid, a part-time secretary, drove a Jaguar and shopped for clothes at Dior and Givanchy. The apartment they shared was adorned with the best abstract art and she regularly appeared in magazines giving out style and beauty tips. To the outside observer she appeared to have fully embraced the life of a Parisian sophisticate, but beneath the façade she remained unsure of who she was or what she wanted from life.

In her next film role, Jean was cast opposite Jean-Paul Belmondo again in Echappement Libre (Backfire), a French thriller directed by Jean Becker. Belmondo plays a smuggler trying to offload three hundred kilos of gold hidden in the back of his Triumph sports car, while Jean, posing as a photojournalist, plays his chic, laid-back accomplice. The 9-week shoot took place largely on the road in cities all over Europe and the Middle-East. The result was a lightweight, but fun, 1960s style caper movie that did good business in France when it was released.

In 1965, Jean returned to America at the behest of Columbia to make Moment to Moment, a romantic thriller in the Hitchcock tradition, in which she played an elegant married woman living on the Riviera who has an affair that leads to murder. Later in August, she began work on A Fine Madness, an offbeat comedy about a rebellious Greenwich Village poet and his battles with the academic establishment. Sean Connery, then at the height of his fame for playing James Bond, was cast as the poet, with Jeanne as a woman with whom he has an affair. It was a one-dimensional role and working on the film was an unpleasant experience for Jean. She threatened to quit several times but reluctantly agreed to continue because she didn’t want to get a reputation for being unprofessional.

In truth, Jean was becoming increasingly disillusioned working within the Hollywood system. In an interview she made her feelings clear, “There are none of the friendly, family feelings that I get when I work in France. In France, you know if you’re making a movie, you’re going to sit around waiting in a café, which is not disagreeable. Here they give you some superb trailer with a Frigidaire and a stove. I keep expecting to find a warmth to the work in Hollywood which doesn’t exist. The unions have imposed so many people for each job there is no longer a sense of personal responsibility. I’m a lot less nervous when I get up in the morning to go to work now. But some of the joy has gone out of acting for me.”

At home in Paris, Jean spent the Christmas holidays with Ramon and Diego. By now their marriage had evolved into something more like a father/daughter relationship. Jean craved Ramon’s approval and sought his guidance in her career. Acting was proving less rewarding for Jean than it had been, and with the first flush of youth now gone, her image was less easy to define. She had gained refinement and an apparent sophistication, but the public perception was not the reality. When people remarked on her self-assurance she felt dismayed as she told Cosmopolitan magazine, “People have a strange picture of me. I’m, not at all the steady, calm person they seem to think I am. That’s part of the masquerade that will never cease to amuse me. I’m not really serene. I’m a nervous wreck.”

This duality in Jean’s character made her an ideal casting choice for Claude Chabrol’s World War II drama Le Ligne de Demarcation (The Line of Demarcation, 1966), in which she played the respectable English wife of a French Count (Maurice Ronet), who helps two Allied spies make their way over the line to freedom. More a parody of the Resistance than a celebration, the film nevertheless did well at the box office. Chabrol cast Jean again in his next film, La Route de Corinth (The Road to Corinth, 1967), a lightweight French-Italian spy thriller that failed to impress anybody, including the director himself.

Taking some time out from working, Jean accompanied Ramon on a lecture tour of Eastern Europe, followed by a return to Marshalltown for her annual visit. With still no offers forthcoming from Hollywood, Jean accepted a role in Estouffade à la Caraibe (Revolt in the Caribbean, 1967), which took her to the country of Columbia for two months. The poverty and inequality she witnessed there appalled her and added further to her growing social consciousness.

Frustrated by the roles being offered to her, Jean agreed to star in a film directed by Ramon based on one of his own short stories titled Birds of Peru. Chronicling the adventures of a nymphomaniac who feels compelled to have sex with every man she meets, the film was a critical and commercial disaster and marked an all time low point in Jean’s career. She felt humiliated and angry that her husband had so abused the trust she had placed in him, marking a further rift in their already difficult relationship.

If Jean thought Birds of Peru might spell the end of her career, then she must have been pleasantly surprised when, soon after, Hollywood in the shape of Paramount Studios, signalled their interest in casting her in their big budget musical Paint Your Wagon. Jean was eager to play the part and agreed to do a screen test with co-stars, Lee Marvin and Clint Eastwood. The test proved a success and she was signed at a salary of £120,000. While in preparing for the film, Jean moved to LA, rented a luxury home in Beverly Hills, and began taking singing lessons.

News of her high profile casting quickly spread and she was soon being inundated with scripts. She accepted a supporting-role in Pendulum, a low-budget police drama directed by George Schaefer for Columbia set in Washington DC. Her participation was delayed, however, when she received the shocking news that her eighteen-year-old brother David had been killed in a car accident. She immediately flew to Marshalltown to consol her parents. When she finally did arrived in Washington to film her part, the news reported that Martin Luther King had been assassinated. The city erupted like a tinderbox. There were protests in the streets and fires broke out in the commercial districts. “It is horrible,” Jean wrote to a friend. “The indifference of the white population is almost total. Instead of improving conditions in the ghetto, they are buying arms to defend themselves. You get the impression of being in a profoundly sick country which doesn’t believe in its illness.”

Jean was, by now, becoming increasingly known for supporting liberal causes. As a result she was often solicited for money and asked to sign petitions. Romain, by contrast, had little time for Hollywood liberalism as well as those who exploited it. “I have never met a more typical American idealist,” he said of Jean. ‘That is to say, an easy mark.”

Ironically, when riots broke out in Paris in May 68 in support of many of the causes she espoused, Jean was halfway around the world filming Paint Your Wagon in the rural splendour of Oregon. Paramount Studios were gambling this highly-expensive musical would replicate the success of earlier blockbusters like The Sound of Music, and had built an elaborate set in the middle of the wilderness to which Jean and her co-stars, Lee Marvin and Clint Eastwood, were flown in by helicopter each day from the nearby town of Baker City. The cost of transporting cast and crew amounted to $80,000 a day and the production soon went over-budget. Jean relied on her friendship with her co-stars to relieve the boredom of the long, drawn-out shoot. Consequently she fell into an affair with Eastwood, who, like her, was married at the time. Hearing rumours of the affair, Gary flew to the set and confronted Eastwood, challenging him to a duel. Nothing came of it, but afterwards Jean called her publicist and told her she was in love with Eastwood and was planning to leave her husband. The announcement was made in the press in September 1968. Their relationship, however, did not last beyond the end of the filming in October.

Now living alone in LA, Jean became something of a recluse. According to friends she was drinking more than usual and taking valium to calm her nerves.

“Without a man, I’m like a ship without a rudder” she confessed to a friend.

It was in this frame of mind that Jean first met Hakim Jamal in October of 1968 on a flight from San Francisco to Los Angeles. He was born in Boston’s black ghetto in 1931 with the name Allen Donaldson. “Jamal” was a former criminal, alcoholic, and heroin addict. When Jean met him, he had cleaned up his image and started a family. He also now sported a goatee beard and African hat, an image that reflected his admiration for Malcolm X. Jamal ran a Foundation in Compton, where he promoted the teachings of Malcolm X. He and his wife had also set up a Montessori school for local children. By the time the plane touched down in LA, Jean had promised to give money to the Foundation, and in the weeks that followed she would become increasingly close to Jamal.

In 1969 Jean co-starred in the big-budget disaster movie Airport, alongside Burt Lancaster, Dean Martin and Helen Hayes. Jean played the airport’s public relation's person who is secretly in love with Lancaster's character. Her salary of $150,000, plus $1000 a week in expenses, was the highest of her career, but the experience of working on the film left her feeling more jaded by Hollywood than ever. ‘They aren’t interested in me,” she told Paton Price. “They want a puppet.”

Location filming took place at the Minneapolis–St Paul International Airport in the freezing temperatures of late February and early March. The crew then moved to the Universal Studios lot, where a full mock up of a 707 airplane took up an entire soundstage.

Meanwhile, Jean's support for Hakim Jamal continued. She organised fundraisers for his foundation and bought the Montessori school a bus. She also donated money to the Black Panthers and allowed them to use her Beverly Hills home as a meeting place. By now she was in a romantic relationship with Jamal leading his wife to Dorothy to hire a private detective to prove his visits to her house were not innocent. When she found out the truth, she called Jean at her house and told her to leave her husband alone.

Hakim's wife, however, was not the only person with an interest in Jean's affairs. The FBI had the Black Panthers under surveillance and now opened a file on Jean. They listened in to her phone calls, including those to Jamal, as well as a leading member of the Panthers called Raymond Hewitt. It has been suggested that Jean’s radical politics, and the FBI campaign against her, led to her effective blacklisted in Hollywood as she was never hired for a studio film again, despite Paint Your Wagon and Airport being among the biggest box office hits of 1969 and 1970.

In the summer of 1969 Jean was in Rome playing another schizophrenic character in Dead of Summer directed by Nelo Risi. Later in the year she went to Mexico to star in Macho Callaghan, an American-Mexican film set during the American Civil War, co-starring David Janssen. While making the film in Mexico she became romantically involved with student revolutionary by the name of Carlos Navarra.

By early 1970 Jean was back in Paris. Jean and Romain had agreed to keep the apartment they had shared during their marriage to make things easier for their son. They built a wall in the middle of the apartment, but continued to share a kitchen. Jean then discovered that she was pregnant. Romain believed the child was his but Jean confessed to friends that the real father Navarra.

In 1970 the FBI created the false story from a San Francisco-based informant that the child Jean Seberg was pregnant with was fathered by Raymond Hewitt, the Black Panthers’ Minister of Education. The story was reported by gossip columnist Joyce Haber of The Los Angeles Times, and was also printed by Newsweek magazine. Jean, who had been suffering from depression and paranoia, attempted suicide by taking sleeping pills. She recovered, but two weeks later went into premature labour, and on August 23 gave birth to a 4lb baby girl. The child died two days later.

While recovering in hospital Jean was visited by members of the Black Panthers who, she claimed, tried to take her credit cards, her money, and the keys to her car. It was the beginning of her disillusionment with the movement. Meanwhile Romain wrote an article in France-Soir blaming Newsweek for Jean’s miscarriage.

By mid-September Jean was determined to return with the body of her child, whom she named Nina, to Marshalltown to be buried. In the second week of September she boarded a plane in Zurich with her bodyguard. To steady herself for the flight she downed several valiums with whiskey. Midway through the flight she told her bodyguard she was going to wash her hands. Minutes later she burst out of the bathroom completely nude, trailing the bandages from her operation. She was screaming that the plane was being hijacked. Eventually she calmed down and spent the rest of the flight downing more tranquillizers so that when the plane touched down in Chicago she was in a drugged daze.

After returning home Jean recovered some of her composure. She wrote to Huey Newton, the leader of the Black Panthers, withdrawing her support. She then wrote a second letter to the Reverend Jesse Jackson in which she pledged half of any winnings from her Newsweek libel case to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. On September 16th the child’s body arrived in Marshalltown in an oak casket. The body was put on display for two days before being buried.

Jean spent November 1970 in a health clinic in Paris. She remained emotionally distraught and began to believe that ordinary people passing on the street outside were CIA agents. Doctors treated her with heavy doses of medication. Visitors were shocked by her overweight and haggard appearance. One noticed that the entire inside of her mouth and her gums were black. Maurice Ronet paid a visit to the clinic and observed that, “Jean was astounded, almost intoxicated, by the whole notion of injustice. She would speak of the hunger of little children and how it hurt her. At the same time she took such an exalted tone that you almost suspected her of playing a role. Already she was weaving this vast conspiracy between her self and the world.”

Once she left the clinic in December, Jean managed to regain her health but her bitter feelings towards Gary came to the fore with the publication of his new novel White Dog which denounced both racism in America, and what he saw as the misguided activism of celebrities like Jean. Commenting on the novel, Jean wrote: “It is the hatred of someone who is incapable of loving anything or anyone except fictitiously, and that I know to be a fact… He has lost any hold he could have had over a naive girl.”

Despite their differences, Jean agreed to act in Gary’s next directorial effort, a political thriller about the international drugs trade titled Kill! Filming took place in Spain in the spring of 1971, but quickly became tortuous and disorganised when Romain fell out with his producers Ilya and Alexander Salkind who wanted the film to be a violent commercial hit. In the end neither party was happy with the result, nor were the critics who gave the film damning reviews when it was released.

Meanwhile Jean and Gary’s lawyers had filed a suit against Newsweek for their article about Jean’s baby. The trial dragged on for 6 months. In the end, the court did acknowledge that the magazine had invaded their privacy and they were awarded $11,000. It was small compensation for what they had lost.

Forced by financial necessity to return to work, Jean took roles in two Italian films: Questa Specie d’Amore (This Kind of Love, 1972), a complex family drama adapted by Alberto Bevilacqua from his own novel, and Camorra (Gang War in Naples, 1972), a violent crime saga directed by Pasquale Squitieri. Jean’s last major film, The French Conspiracy (1972) took on subject matter closer to her heart. Inspired by the true story of the assassination of the Morrocan politician Mehdi Ben Barka in Paris in 1965, The French Conspiracy, directed by Yves Boisset, featured an all-star cast including Jean-Louis Trintignant and Michel Piccoli. Jean played a leftist activist who helps a journalist played by Trintignant who is trying to discover the truth about what happened. While the critical response to the film was divided, the film became one of the top box-office attractions in France that year.

The success of The French Conspiracy did not reignite Jean’s career. By 1972 there was a new generation of screen idols and Jean was at an age when she was no longer convincing as either ingénue or character actress. It was at this time that Dennis Berry, a 27-year-old American living in Paris with ambitions to become a film director, came into Jean’s life. His energy and sense of humour made Jean feel happier. On March 12, 1972, they flew to Las Vegas where they were married in the Chapel of the Bells, a 24-hour marriage parlour.

When Jean married Barry, she believed he could be the one to bring about a renaissance in her career, but two years into their marriage he had yet to make a film. Despite all the money she had made in her career, she was now broke and was forced to take anything she could get. Her film roles at this time included a Spanish horror movie, The Corruption of Chris Miller (1973), and a Canadian suspense drama called Cat and Mouse (1974).

In Paris Jean and Berry’s apartment on the Rue de Bac became a hive of visitors and a refuge where wannabe Left Bank writers, filmmakers and artists congregated. Among the unconventional bohemians who visited them was the young director Philippe Garrel. Garrel was still only in his mid-twenties but had already made a name for himself as a director with 10 films under his belt. He told Jean he wanted to make a movie with her. It was to be on the theme of solitude and would star actors he considered to be authentically lonely, including his girlfriend of the time, the singer and actress Nico. Shot in black and white with no sound, The High Solitudes is a typically enigmatic film that defies explanation but offers a haunting depiction of Jean Seberg’s decline.

One night, soon after they made the film, Garrel visited Jean at her apartment. Jean had too many drinks and when Garrel got up to leave, she begged him to stay for one more glass. He began to leave anyway, at which point she smashed her glass and slit her wrists. Garrel wrapped an improvised tourniquet around her wrists as she cried, “Let me go, I want to die, let me go!” After this incident Jean was returned to the mental health clinic.

Jean spent much of 1974 in and out of clinics. This was a particularly difficult for Dennis Berry who had finally gained funding for his debut feature, Le Grand Délire (The Big Delirium) in which Jean was to star. All through pre-production he was never sure if she would be fit to act in it or not. In the end she did pull herself together sufficiently to take part but the film was a strain to make and did poorly at the box office when it was released.

Jean then returned to Rome to film a marriage melodrama, White Horses of Summer. The film ends with Jean’s character and her husband reuniting when their little boy has an accident. Filming the scene, with its echoes of her own experience, was traumatic for Jean. When Dennis Berry arrived in Rome to visit her, Jean told him she and another actor in the film were involved in a conspiracy to smuggle the Black Panther Huey Newton out of the US. Dennis quickly realised that Jean wasn’t involved with Newton at all and was now retreating into a fantasy world.

In 1976 Jean received a letter from the US Department of Justice confirming that she had been a target of the FBI’s Cointelpro investigation. At the same time the Senate Select Committee issued a report on misconduct at the FBI, which confirmed the FBI’s role in publicising the rumour that Jean’s baby was fathered by a black radical.

Jean’s last film was an adaptation of Ibsen’s The Wild Duck in which she appeared in a small part opposite German actor Bruno Ganz. By the summer of 1976, Dennis and Jean’s marriage was falling apart. The arguments had increased so they decided to separate. A few weeks later Berry got a call from a Spanish actor who told Dennis that Jean was cracking up in a hotel room in Madrid. Dennis rushed there and found Jean in a complete state of delusion. He took her back to Paris and checked her in to a high security sanatorium where Jean was put on lithium.

After her release, Jean and Dennis patched up their relationship and moved back in together for a time. But what had become apparent to Jean’s closest friends was that she was on a path of self-destruction and was growing steadily worse. One friend described her as “the most anguished person I’ve ever met.” Finally, Berry gave up on their relationship, packed up his things, and moved to LA.

After his departure, Jean’s apartment became a chaotic hangout for drug addicts and petty crooks. Sometimes she would leave the chaos of the apartment and go out to late-night bars and clubs, often staying through the night until daybreak. Here she would down drink after drink and engage other patrons in endless debates about politics. Her star name had now faded and the job offers had dried up. Occasionally, a director or screenwriter in awe of Breathless would contact her about a project, but after meeting her in person they would invariably change their minds.

In late 1977, Jean attempted to dry out from the drink and drugs and lose weight at a clinic. After 6 weeks on a protein shake diet she slimmed down and once more looked like a version of her old self, however, as one friend commented, “From a distance she looked twenty-five but up close you could see the years.”

In February 1979 Jean spoke to a reporter from the International Herald Tribune. She said she was being followed and feared for her life. A stay in a state mental hospital followed that interview. Some friends wanted her to move to a less depressing place, but Jean, who now had a permanent limp in one leg, couldn’t afford anywhere else. She now depended on her ex-husband Romain Gary for funds.

In the spring of 1979 Jean went home to her apartment in Paris and hung out at a Moroccan bar in her neighbourhood. Here she met a man in his twenties named Ahmed Hasni. Soon after, he moved into Jean’s apartment. Hasni was not working and occasionally Jean would have to call friends for money for food. Hasni persuaded her to sell her second apartment on the Rue du Bac so that he could use the money to open a Barcelona restaurant. The couple departed for Spain, but she was soon back in Paris, alone.

On the night of August 30, 1979, Jean disappeared. After she went missing, Hasni told police that he had known she was suicidal for some time. He claimed that she had attempted suicide in July 1979 by jumping in front of a Paris subway train. On September 8, nine days after her disappearance, her decomposing body was found wrapped in a blanket in the back seat of her Renault, parked close to her Paris apartment in the 16th arrondissement. Police found a bottle of barbiturates, an empty mineral water bottle, and a note written in French from Seberg addressed to her son. It read, in part: "Forgive me. I can no longer live with my nerves." Her death was ruled a probable suicide by Paris police.

Romain Gary called a press conference shortly after her death where he publicly blamed the FBI's campaign against Seberg for her deteriorating mental health. Gary claimed that Seberg became psychotic after the media reported a false story that the FBI planted about her becoming pregnant with a Black Panther's child in 1970. Romain Gary stated that Seberg had repeatedly attempted suicide on August 25, the anniversary of the child's death.

Seberg was buried in the Cimetière du Montparnasse in Paris.

In December 1980, Romain Gary committed suicide.

| FILMS WITH NEW WAVE DIRECTORS |

French Title |

English Title |

Year |

Director |

Role |

| A bout de souffle |

Breathless |

1960 |

Jean-Luc Godard |

Patricia Franchini |

| Les plus belles escroqueries du monde (segment "Le Grand Escroq")

(scenes deleted) |

The World's Most Beautiful Swindlers |

1964 |

Jean-Luc Godard |

Patricia Franchini |

| Le ligne de demarcation |

Line of Demarcation |

1966 |

Claude Chabrol |

Mary, comtesse de Damville |

| La route de Corinthe |

The Road to Corinth |

1967 |

Claude Chabrol |

Shanny |

Year - Film - Role

1957 Saint Joan - St. Joan of Arc

1958 Bonjour Tristesse

- Cecile

1959 The Mouse That Roared

- Helen Kokintz

1960 Breathless

- Patricia Franchini

1960 Let No Man Write My Epitaph

- Barbara Holloway

1961 Time Out for Love

- Ann

1961 Love Play

- Kate Hoover

1961 Five Day Lover

- Claire

1962 Congo vivo

- Annette

1963 In the French Style

- Christina James

1964 The World's Most Beautiful Swindlers

- Patricia Leacock

1964 Backfire

- Olga Celan

1964 Lilith

- Lilith Arthur

1965 Diamonds Are Brittle

- Bettina Ralton

1966 Moment to Moment

- Kay Stanton

1966 A Fine Madness

- Lydia West

1966 Line of Demarcation

- Mary, comtesse de Damville

1967 The Looters

- Colleen O'Hara

1967 The Road to Corinth

- Shanny

1968 Birds in Peru

- Adriana

1968 The Girls - documentary

1969 Pendulum

- Adele Matthews

1969 Paint Your Wagon

- Elizabeth

1970 Airport

- Tanya Livingston

1970 Dead of Summer

- Joyce Grasse

1970 Macho Callahan

- Alexandra Mountford

1972 Kill! Kill! Kill! Kill!

- Emily Hamilton

1972 This Kind of Love

- Giovanna

1972 Gang War in Naples

- Luisa

1972 Plot

- Edith Lemoine

1973 The Corruption of Chris Miller

- Ruth Miller

1974 Les hautes solitudes - silent film w no named characters

1974 Mousey

- Laura Anderson / Richardson

1974 Ballad for the Kid (Short film) - La star

1975 White Horses of Summer

- Lea Kingsburg

1975 The Big Delirium

- Emily

1976 The Wild Duck

- Gina Ekdal

|

|