film trailer

Why it’s important?

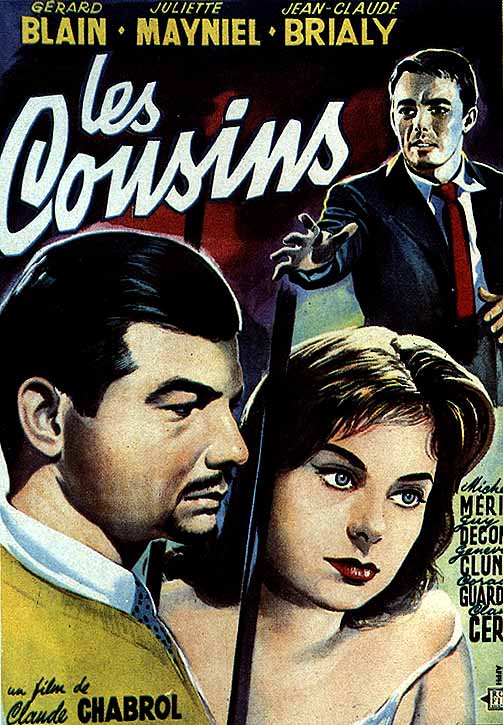

Although Le Beau Serge is often recognized as the first French New Wave film, the more assured, stylistically refined and morally ambiguous Les Cousins better represents the type of cinema commonly associated with both Claude Chabrol and the Nouvelle Vague.

Les Cousins marked the first of fourteen film collaborations between Chabrol and co-writer Paul Gégauff. Gégauff, a dialogue specialist, would make a major contribution to the tone and content of Chabrol's work over the next eighteen years.

Making her debut in a Chabrol film, the actress, Stéphane Audran, appears in a small role as a party guest. Audran would go on to marry Chabrol and star in many of his greatest films.

Paris plays a significant role in the film. Chabrol filmed exteriors on location in the city, which was unusual for French cinema of that era. This decision added an element of realism to the film and allowed the city itself to become a character in the story.

Les Cousins went on general release in France on 11 March 1959. A critical and commercial success, it built on the promise of Le Beau Serge, establishing Claude Chabrol as an important new voice in French cinema.

Production Notes

Le Beau Serge premiered at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival. The favourable reviews it received helped Chabrol find a foreign distributor for the film. Their advances, combined with a 32-million-franc subsidy granted to Chabrol by the Centre National de la Cinematographie Film Aid Board, enabled production of Les Cousins to begin, even though Le Beau Serge had yet to go on general release.

Chabrol chose to work again with several of the same personnel he had worked with on Le Beau Serge, including actors Gérard Blain and Jean-Claude Brialy, cinematographer Henri Decaë, camera operator Jean Rabier, and editor Jacques Gaillard. The film also marked his first collaboration with Paul Gégauff, with whom he co-wrote the script, and with the actress Stéphane Audran, who has a small role as one of the party-going bohemian set.

Les Cousins was shot in July and August of 1958 on location in Paris and at the Studios de Boulogne-Billancourt. Chabrol later explained why he chose to work in a studio:

"I used the studio for Les Cousins purely for economic reasons. We calculated that given how much of the film was set in that flat occupied by the two cousins, renting a flat which didn't have the features I needed would be just as expensive as building a small set in the studio. We took the smallest studio in Boulogne. It was terrible for the set designers who were Saulnier (Jacques Saulnier) and Evein (Bernard Evein). The back projection was almost up against the wall of the set. Saulnier said, "How do you expect me to light that?" But he managed it perfectly well. "

By the fifth week of filming funds were running out. The subsidy had been spent. Four days before being forced to stop filming, Chabrol found a French distributor who agreed to buy both Le Beau Serge and Les Cousins for the domestic market. The money from this deal was enough to complete the film.

Film Review

Themes

Claude Chabrol's Les Cousins (1959) is a masterful exploration of contrasting personalities, moral ambiguity, and the fragility of human relationships. As one of the early films of the French New Wave, Les Cousins blends psychological depth with incisive social critique, crafting a narrative that resonates with both universality and specificity. The film delves into timeless themes such as innocence and corruption, the randomness of fate, and the alienating effects of modern urban life, creating a rich tapestry that continues to engage and provoke audiences.

Innocence vs. Corruption

At the heart of Les Cousins lies the clash between two fundamentally opposing characters: Charles (Gérard Blain), a shy, principled provincial student, and Paul (Jean-Claude Brialy), his sophisticated and morally ambiguous cousin. This dichotomy reflects a larger tension between innocence and corruption, with Charles embodying traditional values such as diligence, sincerity, and restraint, while Paul represents the seductive allure of decadence, urbanity, and moral relativism.

The Parisian environment, a hub of intellectualism and hedonism, becomes a testing ground for Charles's ideals, which are gradually undermined by Paul's freewheeling lifestyle. Parties, casual relationships, and an atmosphere of intellectual posturing surround Paul, creating a world where traditional values seem outdated or even naïve. Charles's eventual unravelling highlights the fragility of innocence when faced with the seductive, yet corrosive, forces of modern urban life. This theme serves as a critique of a society that rewards charm and superficiality over sincerity and integrity.

Fate and the Arbitrary Nature of Success

A central theme of Les Cousins is the capriciousness of fate and its role in shaping the destinies of the characters. The film is suffused with a sense of inevitability, reinforced by recurring imagery of clocks and time. Charles, despite his hard work and commitment to his studies, fails his crucial law exam, while Paul, who exerts little effort and lives recklessly, thrives. This disparity underscores Chabrol's suggestion that success and failure in life are often arbitrary, determined more by luck or circumstance than by merit.

The climactic events of the film, including the shocking and tragic ending, further emphasize this idea. Chabrol's use of foreshadowing—such as Paul's cavalier attitude toward danger—creates a pervasive sense of doom, suggesting that the characters are trapped by forces beyond their control. This theme resonates with existentialist ideas prominent in mid-20th-century French culture, reflecting a worldview where human effort and morality are often powerless against the randomness of life.

Moral Ambiguity and Relativism

Les Cousins avoids clear moral dichotomies, presenting its characters as deeply flawed and complex. Paul, for all his arrogance and manipulative tendencies, exudes a charm and confidence that make him a compelling figure. He is not an outright villain but a product of his environment—a man who thrives in a world that values appearance and wit over substance. Meanwhile, Charles, while ostensibly the moral center of the film, is not without his shortcomings. His rigidity and inability to adapt to his surroundings make him a tragic figure but also one who is, at times, frustratingly self-righteous. This moral ambiguity is central to Chabrol's vision, as he avoids passing judgment on his characters. Instead, he uses their interactions to explore the subjective nature of morality and the societal structures that shape human behaviour. The rivalry between Paul and Charles, particularly in their competition for Florence (Juliette Mayniel), becomes a microcosm of this larger inquiry, raising questions about loyalty, love, and the ethics of power dynamics in relationships.

The Alienation of Urban Life

The film's Parisian setting plays a vital role in shaping its themes. The city is depicted as both alluring and alienating, a place of endless opportunities that also fosters disconnection and moral disorientation. Paul's apartment, the primary setting for much of the film, serves as a metaphorical space where intimacy is often shallow and human connections are transactional. Parties, though lively and full of people, highlight Charles's isolation, as he struggles to connect with Paul's social circle.

Chabrol's Paris is not the romanticized city of light but a modern metropolis where traditional values erode under the pressures of ambition, competition, and indulgence. This theme reflects broader anxieties about the changing social fabric of postwar France, as rural, traditional ways of life clashed with the rapidly modernizing and urbanized society of the late 1950s.

The Fragility of Human Relationships

Underlying the film's exploration of morality and fate is a profound meditation on the fragility of human relationships. Paul and Charles's bond as cousins is tested repeatedly, as their opposing worldviews and romantic rivalry strain their connection. Florence, too, becomes emblematic of the impermanence of relationships in a morally ambiguous world. Initially drawn to Charles's sincerity, she ultimately gravitates toward Paul's confidence and charm, highlighting the fickle nature of human attraction.

The film's devastating conclusion underscores the tenuousness of these connections, as trust and understanding crumble under the weight of jealousy, resentment, and despair. This theme resonates throughout Chabrol's broader body of work, which often explores how seemingly strong relationships are undone by betrayal, miscommunication, and the darker impulses of human nature.

The Performance of Identity

Another subtle theme in Les Cousins is the performative nature of identity, particularly in the context of Paul's social circle. Paul's friends, who spout intellectual jargon and engage in ostentatious displays of sophistication, embody a world where appearances matter more than authenticity. Paul himself is a master performer, using his charm and wit to manipulate those around him, while Charles's inability to "perform" in this environment contributes to his alienation and ultimate downfall.

This theme reflects Chabrol's critique of a society increasingly preoccupied with image and social capital, a concern that remains strikingly relevant in today's world. It also reinforces the film's exploration of morality, as characters navigate a world where authenticity is often sacrificed for acceptance and success.

Key moments

The film opens with Charles arriving in Paris from the provinces, full of hope and idealism. A quiet, diligent, and morally upright young man, Charles embodies the traditional values of discipline, modesty, and ambition. He is entering this new world to study law, with the assumption that hard work and decency will guide his way. The setting of his cousin Paul's lavish Parisian apartment immediately sets up the central contrast: Paul, by contrast, is a man of leisure, born into wealth, surrounded by decadent friends, and unburdened by the need to work or conform. This juxtaposition of sincerity versus cynicism, provincial earnestness versus cosmopolitan detachment, becomes the backbone of the film's tension. Charles's polite demeanor and wide-eyed wonder make him seem hopelessly naïve in the world Paul inhabits. From the very beginning, we sense that Charles is out of place, a visitor in a morally ambiguous and seductive landscape.

As Charles settles into life with Paul, he becomes increasingly aware of the hedonism and spiritual emptiness of his cousin's circle. Paul throws extravagant parties that seem never-ending, filled with pseudo-intellectuals, artists, and self-absorbed dilettantes. The apartment becomes a symbol of bourgeois decadence—a playground for the idle rich where nothing seems to matter except aestheticism, irony, and indulgence. Paul, charming and witty, floats through this world with ease, manipulating those around him with his aloof charisma. For Charles, this world is not only unfamiliar but quietly horrifying. He finds the conversations insincere, the people aimless, and the environment lacking the ethical framework he has grown up with. What's most painful for Charles is not just that this world is alien, but that it seems to be winning—Paul thrives effortlessly while Charles must struggle to assert his place.

A significant turning point occurs when Charles meets Florence, a beautiful and elusive young woman. Their initial interaction is tender, almost innocent, and Charles is instantly smitten. To him, Florence represents an ideal: cultured, intelligent, and sensitive. He believes that in loving her, he might find some kind of truth or meaning in this disorienting new environment. He pursues her with patience and restraint, convinced that honesty and sincerity will win her over. However, Florence is more complicated than Charles can comprehend. Though she is touched by his affection, she is also drawn to the darker, more magnetic presence of Paul. For her, Paul symbolizes danger, sophistication, and eroticism—qualities that Charles, for all his decency, does not possess. This love triangle quietly begins to form, setting in motion the film's emotional crisis.

After meeting Paul's friends, Charles makes the first of several visits to a bookshop, where he strikes up a friendship with the avuncular owner. The bookshop scenes serve as subtle yet pivotal moments that reflect the contrasting worlds of the film's central characters, Charles and Paul. The bookshop, a sanctuary of order and intellectual pursuit, aligns with Charles's earnest and idealistic nature. In these scenes, Charles's demeanour—reserved and studious—underscores his alienation from the chaotic, hedonistic lifestyle of his cousin Paul. The environment, marked by neatly arranged books and subdued lighting, stands in sharp contrast to the debauchery of Paul's apartment, symbolising the moral and cultural tension between the cousins. These scenes also act as a quiet commentary on the displacement of traditional values in a modernising world, as Charles's affinity for the bookshop and its proprietor underscores his struggle to find his place amidst the bohemian decadence that defines his cousin's circle.

The turning point in Charles's emotional journey comes when Florence, after vacillating between the two cousins, ultimately sleeps with Paul. The moment is handled with tragic understatement—there is no dramatic confrontation, only Charles's quiet realization of betrayal. What makes this moment so devastating is its inevitability: from the moment Florence entered Paul's world, it seemed only a matter of time before she would succumb to his allure. For Charles, this is more than just romantic rejection; it is a confirmation of a cruel truth—that virtue and sincerity have no place in the world he has entered. Florence's choice, driven by a mix of attraction and self-doubt, reveals the complex dynamics of power, desire, and emotional manipulation. Paul's seduction is not just of Florence, but of the entire moral order that Charles represents. This betrayal leaves Charles emotionally hollow and spiritually unmoored.

Shortly afterwards, the results of the law exams come in, and Charles fails. Paul, who barely studied and mocks the idea of effort, passes with ease. This moment reinforces the film's overarching sense of injustice: those who play the system or reject it altogether seem to succeed, while those who believe in fairness and effort are punished. Charles's failure is not just academic—it is existential. He has come to Paris with a dream, only to find that the values he holds dear are not only irrelevant, but actively ridiculed. This crushing disillusionment marks the beginning of Charles's psychological collapse. He begins to drift silently through the apartment, emotionally isolated and increasingly incapable of engaging with the people around him. The once-hopeful provincial has become a ghost, consumed by despair and resentment.

In a final act of desperation, Charles takes a revolver that Paul had acquired and loads it with a blank cartridge, intending to frighten or perhaps even kill Paul. It is a moment of quiet, tragic rage—Charles, who has tried so hard to live with integrity, is pushed to the brink. Yet even here, Charles's action is riddled with hesitation and confusion. He does not use a real bullet, perhaps out of moral conflict or incompetence. The attempt fails; Paul is startled but unharmed, and Charles's final effort to assert power or meaning in his life ends in impotence. This scene crystallizes the film's central theme: the futility of moral certainty in a world that no longer respects it. Charles, who once believed in rational justice and emotional truth, is reduced to a desperate man with an empty gun.

In the film's cruellest and most poetic twist, Charles dies not by his own hand or through a moral reckoning, but by pure accident. Paul, oblivious to the earlier events and treating the gun as a toy, unknowingly loads it with a live cartridge and fires it during a careless moment—killing Charles. The randomness of this act and Paul's total detachment from its consequences deliver the film's fatalistic conclusion. Charles's life ends not in a grand gesture or moral vindication, but in a moment of meaningless chance. There is no justice, no redemption—only irony and death.

Style

Les Cousins exemplifies Claude Chabrol's early, deceptively classical style, which conceals deep ironies and unsettling emotional undercurrents. Though often grouped with other French New Wave films, Les Cousins is more formally restrained than the jump cuts and handheld chaos of Godard or Truffaut. Chabrol opts instead for smooth tracking shots, composed frames, and measured pacing, using traditional cinematic language to critique bourgeois values from within. The apartment setting, almost theatrical in its scale and opulence, becomes a character itself—an enclosed, decadent space where moral collapse unfolds under the guise of polite society. This tension between visual elegance and existential dread defines the film's unsettling mood.

Chabrol's use of lighting and spatial dynamics enhances the psychological tension between the characters. Paul's apartment is bathed in soft, artificial light that creates a kind of luxurious haze—inviting but detached from reality. In contrast, the scenes outside the apartment are often colder, starker, and more austere. These visual contrasts reinforce the film's central dichotomies: city vs. province, decadence vs. discipline, irony vs. sincerity. Chabrol rarely uses overt symbolism, but the way characters move through space—Paul lounging aimlessly, Charles hunched over books—quietly communicates the shifting power dynamics at play.

The film's sound design is subtle but purposeful. Dialogue is often drowned out by ambient noise—party chatter, classical music, typewriters—mirroring Charles's internal dislocation. Paul is frequently accompanied by records and radio broadcasts, reinforcing his detachment and control over his environment. Music, in particular, is weaponized to express mood rather than to underline emotion. The use of classical pieces, like Wagner, feels ironic in their grandeur, contrasting sharply with the emptiness of the characters' pursuits. Silence, too, becomes significant in the film's latter half, as Charles's isolation deepens and tension builds toward the tragic climax.

Performances

The performances in Les Cousins are deliberately understated, yet emotionally potent. Gérard Blain, as Charles, brings a quiet intensity to the role—his stiff posture and earnest expressions perfectly capturing a young man out of step with his surroundings. His performance is marked by restraint, allowing the audience to feel the full weight of his increasing isolation and quiet despair. In contrast, Jean-Claude Brialy as Paul is all charm and cool detachment. Brialy's performance is slick, controlled, and subtly menacing; he plays Paul not as a villain, but as someone who cannot conceive of consequence. Their chemistry is crucial—Blain's vulnerability makes Brialy's flippancy all the more cruel. Juliette Mayniel as Florence embodies ambiguity. Her performance resists easy interpretation: she is distant, alluring, and perhaps hollow, a reflection of the moral fog surrounding all three characters. Together, the cast forms a triangle of muted emotion, where silence and body language often speak louder than words.

Reception

After receiving mostly positive reviews in France, Les Cousins went on general release in French cinemas on 11 March 1959. It had 1,816,407 admissions in France (six times more than Le Beau Serge) and was the second most popular film of Chabrol's career. In June 1959, it won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival.

Internationally, reviews of Les Cousins were more mixed. In the opinion of Variety's film critic, "director Chabrol has gone in for a little too much symbolism. The characters sometimes remain murky and too literary rather than real. But a concise progression, fine technical aspects, and a look at innocence destroyed by the profane keep it absorbing despite the slightly pretentious treatment at times."

Bosley Crowther commented in The New York Times that, "Chabrol has more skill with the camera than he has with the pen, and his picture is more credible to the eye than it is to the skeptical mind. But it is nonetheless overwhelming, and it is beautifully played by much the same cast that performed for him in Le Beau Serge."

Defending the film, Pauline Kael wrote: "Les Cousins, more than any other film I can think of, deserves to be called The Lost Generation, with all the glamour and romance, the easy sophistication and quick desperation that the title suggests."

A typically perceptive review came from the pen of Jean-Luc Godard, Chabrol's friend and colleague at Cahiers du Cinéma:

"The story which Claude Chabrol tells in his second film, Les Cousins, is of beautiful simplicity, or if you prefer, simple beauty. At first sight it is a story after Balzac, for in it one sees the Rastignac of La Pére Goriot taking up his abode with the Rubempré of Une étude de femme. But Les Cousins is also a fable by La Fontaine, since one sees a town rat (Jean-Claude Brialy) lording it over his country cousin (Gérard Blain) while a grasshopper (Juliette Mayniel) flits from one to the other with a very Parisian disdain. Les Cousins, in short, is the story of a match between laughing Johnny and crying Johnny. And Chabrol's originality is that he has let laughing Johnny win in spite of his wicked airs.

For the first time in a very long time, in fact, perhaps since La Règle du jeu (The Rules of the Game, Jean Renoir, 1939), we can watch a French film-maker taking his characters to their logical conclusion, and making of their development the Ariadne's thread of his scenario. In Le Beau Serge, this was already one of the film's principle features. But it is even more noticeable in Les Cousins. One is interested by the characters not so much because they study hard, sleep with the "good-time girls", or go on the spree; no, one is interested in them because their exploits reveal them at each instant under a new light. This is the important thing that Chabrol has been able to pass with masterly skill from the theoretical beauty of a script by Paul Gégauff to its practical beauty – in other words, its mise-en-scène. It is important because it is very difficult. Antonioni, for instance, wasn't able to make it in Il grido (The Cry, 1957).

Between Le Beau Serge and Les Cousins there is the same difference as between a Cameflex and a Super Parvo. Almost constantly in pursuit of the characters, Chabrol's big studio camera hunts the actors down, with both cruelty and tenderness, in all four corners of Bernard Evein's astonishing décor. Like some great beast it suspends an invisible menace over Juliette Mayniel's pretty head, forces Jean-Claude Brialy to unmask the great game, or imprisons Gérard Blain under double key, i.e., A double tour (1959, Chabrol's next film) with a fantastic circular movement of the camera. When I say that Chabrol gives me the impression of having invented the pan – as Alain Resnais invented the track, Griffith the close-up, and Ophuls reframing – I can speak no greater praise."

Look out for

In addition to the returning stars Jean-Claude Brialy and Gérard Blain—who notably swap roles from Le Beau Serge—Les Cousins also features Claude Cerval, returning in a markedly different role from the priest he played in Le Beau Serge, now portraying Paul's scheming and malevolent friend, Clovis.

Stéphane Audran appears as part of Paul's wider university circle of friends—a small role here, but the beginning of what would become a significant presence in both Chabrol's personal life and cinematic career.

Guy Decomble, who plays the amiable bookshop owner who befriends Charles, also appears as the much sterner schoolteacher in François Truffaut's Les Quatres cents coups (1959), where he oversees Antoine Doinel.

During his first visit to the bookshop, Charles borrows Honoré de Balzac's Lost Illusions—a novel whose title and plot, centered on a provincial youth's disillusioning pursuit of success in Paris, closely mirrors the themes and trajectory of Les Cousins.

On his second visit to the bookshop, a movie tie-in edition of Paths of Glory—the novel adapted by Stanley Kubrick for his 1957 film about the French army in World War I—is visible on the bookstand.

Where to go from here

To delve deeper into Chabrol's filmography, start with his debut film, Le Beau Serge (1958), often considered a companion piece to Les Cousins. Where Les Cousins explores urban decadence, Le Beau Serge takes a rural perspective, examining friendship, jealousy, and morality with the same incisive psychological depth.

For a look at Chabrol's later work, explore his masterful psychological thrillers such as La Femme Infidèle (1969) and Le Boucher (1970). These chilling studies of relationships, infidelity, and violence show Chabrol's evolution as a filmmaker while maintaining his signature interest in human complexity.

Love triangles, with their inherent drama and moral ambiguities, became a recurring motif in the films of the French New Wave, serving as a lens through which to explore themes of desire, betrayal, and human connection. Some notable examples include Louis Malle's Les Amants (1958), Alain Resnais's Last Year at Marienbad (1961), François Truffaut's Jules et Jim (1961) and La Peau douce (1964), Jean-Luc Godard's Une femme est une femme (1961), Agnès Varda's Le Bonheur (1965), and Eric Rohmer's Ma nuit chez Maud (1969).

Other recommended films of this era that explore themes of moral ambiguity, interpersonal tension, and the psychological intricacies of relationships, would include Roman Polanski's Knife in the Water (1962), which similarly delves into a tense triangular dynamic, combining class conflict with subtle power plays. Michelangelo Antonioni's L'Avventura (1960) offers a meditation on existential ennui and fractured human connections, paralleling the disillusionment and complexity seen in Chabrol's characters.

all rights reserved, all content copyright 2008-2025

|